HBO’s “Watchmen” is weird and dangerous, just like it needs to be

Very little about HBO’s Watchmen is safe.

The first scene dramatizes—in graphic detail—the 1921 Tulsa race massacre during which more than 100 black residents were killed by white supremacists (thousands of others lost their homes). Not too long after that, when the story fast-forwards to its alternate reality 2019, squids rain down from the sky.

The entire undertaking is a risk: Alan Moore, the creator of the groundbreaking 1986 Watchmen comic on which the TV series is based, has said repeatedly that he’s not interested in Hollywood adaptations of his work. Some fans agree, arguing the source material should be left alone. But HBO’s Watchmen doesn’t much care for precedent or status quo—and it’s all the better for it.

HBO is hoping that Watchmen, debuting Oct. 20, can be its next centerpiece drama, helping the network pivot back into the zeitgeist after the divisive final season of its longtime crown jewel, Game of Thrones. The comic book series won’t ever be as gargantuan as its fantasy counterpart was. (The show cost HBO about $15 million per episode, while 14 million people watched the finale live on TV—both HBO records.) Watchmen is probably too bold and politically conscious to catch on in the way that the crowd-pleasing Game of Thrones did. Still, it’s likely to be an important success for HBO as it confronts a world without Thrones for the first time since 2010.

Moore’s comic depicted an alternate reality in which masked heroes really existed, and their existence changed the course of history in dramatic ways. The US won the Vietnam War and made Vietnam its 51st state. Global nuclear disaster was narrowly averted in the 1980s when Ozymandias, a former hero (and considered the smartest man on the planet), successfully faked a giant alien squid attack on Earth to force the US and Russia into a reluctant, but ultimately peaceful alliance. Rorschach, another masked vigilante, resolved to expose the conspiracy to the world before he was killed.

The TV series picks up about 30 years after the events of Moore’s story (and not, notably, after the 2009 movie that rewrote his ending). Everything that happened therein—Ozymandias, the squid attack, Rorschach’s death—is canonical. But now, the story has moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, replacing the Cold War anxieties of the original comic with more modern fears, namely white supremacy and the pursuit of racial justice. Oh, and Robert Redford is in the middle of his eighth term as US president.

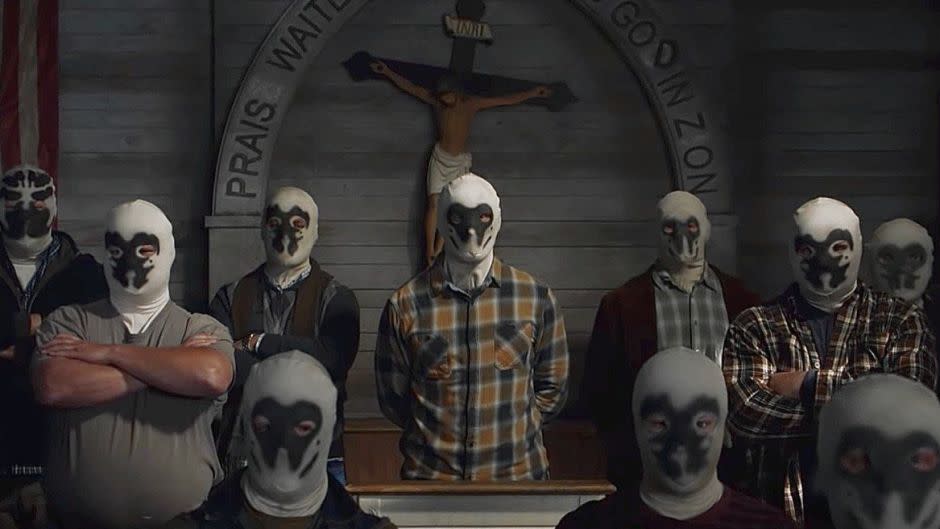

There’s a lot going on here, and the show shies away from none of it. It is the rare mainstream American drama to unflinchingly confront the country’s sordid history of racial violence. (In this alternate reality, residents of Tulsa whose ancestors were affected by the 1921 massacre are given financial reparations—a policy that displeases a local white supremacist cult that hides behind homemade Rorschach masks.) Series creator Damon Lindelof has said his update to the Watchmen universe was partially inspired by writer Ta-Nehisi Coates’ award-winning article in The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations.”

“You’re going to have some people that are not going to feel it because they don’t want their TV shows or films to touch on things that are really happening,” Regina King, who plays the masked detective Sister Night, told Quartz. “But I think the majority of people are here for it. Most of us, as human beings, want to feel like someone else knows their pain and is talking about what they’re talking about.”

Like Lindelof’s previous show, The Leftovers, Watchmen is an audacious feat of storytelling utterly unafraid to ask the scary, existential questions. One theme that emerges clearly through the show’s first six episodes made available to critics is family trauma, and how it’s passed down from generation to generation like a disease encoded into DNA. Another big idea—one borrowed from Moore’s work but even more relevant today given the ubiquity of superhero entertainment— is the psychology of people who put on masks. What kind of person hides their face from the world? Who do they become when that happens? And who holds them accountable?

“How do I say these lines with a straight face? It’s so bonkers.”

Tim Blake Nelson, whose character Looking Glass sulks around most of the time in a creepy, reflective mask, linked that specific wardrobe choice to the man’s personal trauma. “He has trauma in his past, and that trauma has counseled him very strongly not to trust others,” he told Quartz. “And in certain respects, not even to trust his own impulses. He’s chosen a mask that is a manifestly protective metaphor for all that.”

Watch closely.

“These are some really wild scenarios that Damon has come up with,” adds Hong Chau, who plays the mysterious Lady Trieu. “How do I say these lines with a straight face? It’s so bonkers.”

The most existential question of all raised by Watchmen, however, is: What happens when you meet your god? What does he (or she, or it) have to say, if anything? Does he care about you? Are you even real to him? For those familiar with Lindelof’s work on The Leftovers and Lost, these questions won’t surprise you. It’s something the writer has been exploring through TV and film for more than a decade.

And that’s where Watchmen takes the biggest risk. Moore, Lindelof has admitted, is one of his biggest inspirations—a god, if you will. That HBO’s Watchmen exists at all is radical, because it defies the very wishes of its creator. It walks right up to its maker and says that while it will always respect him, it’s doesn’t really care what he thinks. It’s going ahead anyway.

That spirit of defiance is present in every element of Watchmen—from its bold musical choices to its thorny subject matter to its diverse cast and crew. Watchmen not only advances Moore’s story forward, but it also, itself, represents the advancement of American TV in general. The first two episodes are directed by a woman (Nicole Kassell, who also worked with Lindelof on The Leftovers). None of the first six episodes are directed by white men. Half are co-written by women, and two of the six are co-written by black writers. It’s a Watchmen story for 2019, told by people who are living it. Watchmen kicks the post-Game of Thrones era of HBO off with a thrilling and fearless start.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: