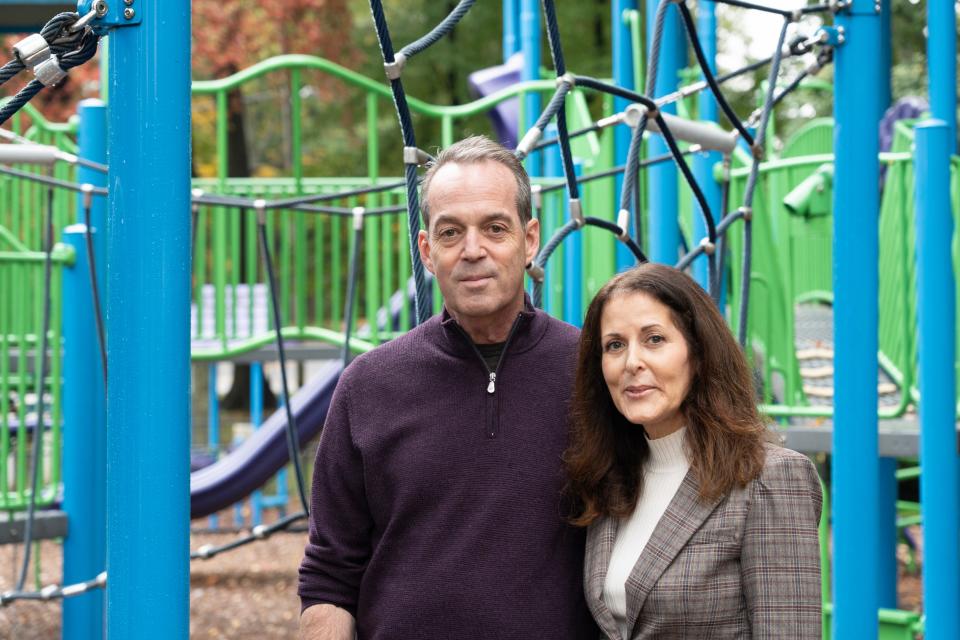

Healing after unimaginable loss: NJ couple expand services to help grieving parents

When Josh and Carolyn Levitt’s son Eli died moments after he was born prematurely in 2020, they felt not only a crushing sense of loss but something many parents experience in the days, weeks and months after losing an infant: isolation.

They didn't know anyone who had lost a child. But a few days later, the Manhattan couple heard through a friend that a small Bergen County support group for grieving parents had recently moved its meetings to videoconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Levitts were soon introduced to Pam and Paul Caine, whose son Griffin died in 1996 just 13 days after he was born. "Pam told us right away that this would be the most challenging thing we would ever face, but also that there was a light at the end of the tunnel because she had gone through it," Josh said. "I can't tell you how comforting that was."

It's hard to calculate how many parents Pam and Paul Caine have helped cope through stillbirths and infant loss over almost three decades since their son died. They don't really keep count, mostly because there is always another family in anguish reaching out for help.

New Jersey averages about six to eight fetal deaths per 1,000 births, a slightly higher rate than the national average, Health Department statistics show. In 2021, there were 636 fetal deaths statewide, in the latest data.

The state infant mortality rate — children dying before their first birthday — was four per 1,000 live births in 2020, according to the March of Dimes. There were 392 infant deaths in New Jersey that year.

Support services for grieving parents are not always readily available in New Jersey. Front-line health care workers are not always trained on how to deal with mothers and fathers who just lost a child. An infant's death is often unexpected. Couples are supposed to leave the maternity ward with the hopes and dreams of a new chapter in life, not in mourning.

"No one is prepared for this type of loss," Pam Caine said. "Parents are in shock. They don’t know what to do. And often, their friends, family and even care providers don't know what to do. It is so far beyond everyone's imagination."

The Caines have run the Griffin Cares support group for years and are looking to expand, having created a foundation last year that allows fundraising on a larger scale. Their videoconference sessions now attract families from beyond New Jersey who have heard of their work mostly through word of mouth.

Discussions often center on everyday situations that can compound grief. How do you handle when friends are pregnant? What do you say to co-workers when you go back to work? Do you try to have another child?

"No one can really understand what you're going through until you talk to other families who've gone through it," Pam said.

Out of tragedy comes hope

Like many support groups, Griffin Cares was born out of tragedy. Griffin Caine came into the world a healthy baby after a normal pregnancy, but just 13 days later he died unexpectedly.

"Everything in our lives was going great, and then I just picked him up one day and he collapsed in my arms," Pam said.

A horrible situation was made worse. The couple said they never received a clear explanation about the cause of Griffin's death. They had difficulty getting an appointment with a therapist in midsummer. The internet was in its infancy in 1996, and searching for a support group was difficult.

A few months later, Paul participated in a charity golf function for the CJ Foundation for SIDS, based at Hackensack University Medical Center. And even though Griffin did not die of sudden infant death syndrome, the couple found solace being among other parents who shared a strong yet terrible bond.

After coordinating with Tenafly officials and raising $20,000, mostly from families, friends and neighbors, the Caines created Griffin Park, a playground in the borough's Roosevelt Commons. It opened in 1997 on what would have been Griffin's first birthday.

As cathartic as the park effort was, the couple thought they could make even more of a lasting impact by using what they had learned to help others. After she trained to be a peer mentor at the SIDS Center of New Jersey, Pam's first effort was helping to train doctors, nurses, social workers and other staff members at Englewood Hospital on how to respond to parents who have just lost a child.

"Traumatic events are like movies that parents can replay forever, and the care providers are often the stars in this movie," Pam said. "Parents don't know what to do when they lose a child, and they're going to ask a lot of questions of their caregivers: Can they hold the baby? Can they name the baby? Can they have pictures taken? So it's essential to have gentle, kind and informed guidance right away."

Part of the mission of Griffin Cares is to pair parents with peer mentors who have lost a child and can help guide them through their grief. Videoconference support groups now meet twice a month with about 12 to 24 couples participating. Many parents attend religiously — especially right after a death. Others drop in from time to time, sometimes when a milestone approaches, like a birthday.

A mission emerges

Carolyn Levitt carried Eli in her womb for 20 mostly uneventful weeks. During a routine scan, doctors discovered that her cervix was already opening, as if she were about to go into labor. Carolyn underwent surgery to stitch her cervix closed. But at 23 weeks she went into labor.

Eli died seconds after he was born — before Carolyn could even hold him.

"It was such an intense level of despair," Carolyn said. "It was unimaginable to us. We never knew of anyone who went through anything like this. I felt like we were stranded alone on this terrible island that we couldn't get off of."

But speaking to Pam Caine a few days later lifted some of that hopelessness.

"Despite what she went through with Griffin, you could tell that she still found meaning and joy in her life," Carolyn said. "That gave us hope."

The Levitts were paired with another couple who had lost their child almost a year earlier. They attended the virtual meetings and befriended couples who shared a common grief but often different stories — early miscarriages, termination for medical reasons, premature births, stillbirths, infant deaths.

"We like to say it's the worst club to join but it has the best members," Carolyn said.

As the Levitts went through the peer therapy that Griffin Cares offers, Carolyn, a psychologist, volunteered to be a peer mentor herself. The couple eventually became members of the foundation's board while juggling careers.

But much of their time is devoted to raising their second son, Noah, who is almost 2. Children born after an infant sibling dies are often called "rainbow babies."

"You never forget the trauma," Josh Levitt said. "You never forget about losing your child. But you do realize how fortunate you are for what you do have and how you can help others."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Unimaginable loss: NJ couple offer help for grieving parents