Health, heritage preserve remain environmentalists’ concerns for Conway hospital plan

Several times a year, state authorities enter the Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve in Conway and start fires.

Portions of International Drive, a mostly four-lane divided highway that connects Carolina Bays Parkway in Myrtle Beach with S.C. 90, are shuttered. Plumes of smoke waft over the area.

But it’s all under control. Called prescribed burns, the blazes are essential to maintaining the preserve’s diverse ecosystem and preventing uncontrolled forest fires.

Still, smoke from the burns, which can last for days, is uncomfortable for some nearby residents and visitors.

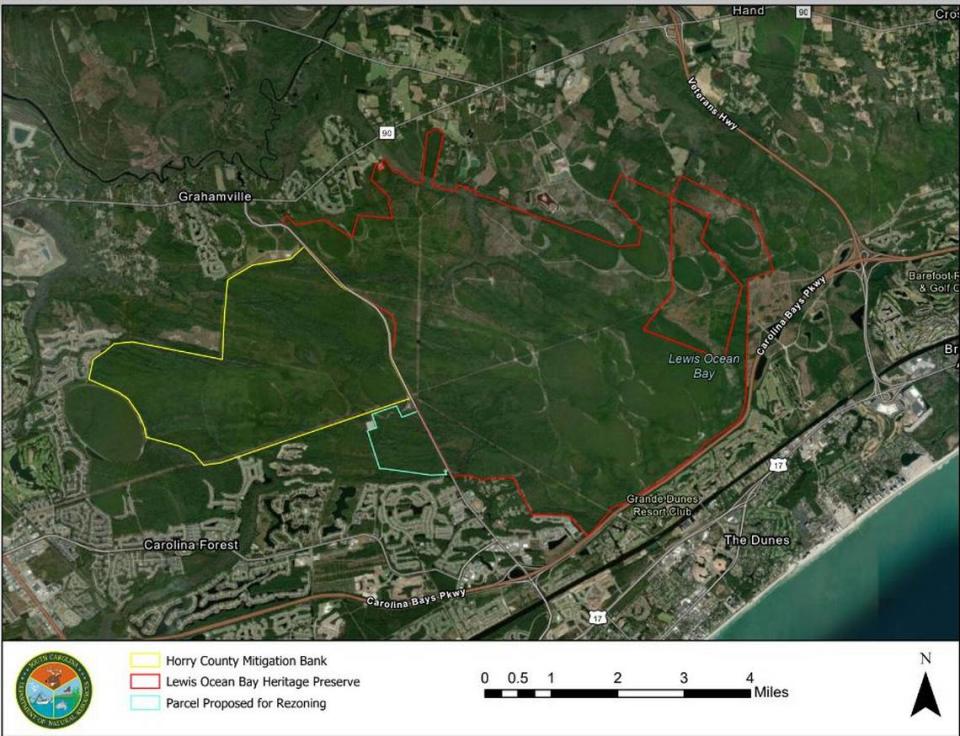

Soon, if the local Conway Medical Center hospital system and Horry County Council get their way, a medical center will be built across from the preserve to care for residents in a rapid-growing area. But placing a hospital so close to prescribed burns has environmentalists and one county council member concerned about the impact on patients, staff and the environment.

“Do we need another hospital? We absolutely do. But that’s not the place to put it,” Councilman Mike Masciarelli said in August. “This is a disaster waiting to happen.”

The property owned by the hospital is within half a mile of Ocean Bay Middle School, Ocean Bay Elementary School and county-owned athletic fields. The property is almost directly across from a new animal hospital being built. The proposed hospital site shares a property line with parts of the residential development, The Farm at Carolina Forest, developed in the mid-90s with nearly 1,000 homes.

But supporters of the hospital and a Harvard University medical researcher say the smoke won’t threaten medical staff, patients and visitors to the hospital.

“The air intakes will utilize the latest filter technologies developed and proven in California to minimize wildfire smoke infiltration,” a hospital spokesperson said in a 2020 statement. Plus, the hospital will be “located far from the burn area, further minimizing smoke infiltration.”

Why, then, have plans for building the hospital been held in limbo for the past three years? In part, it’s because of an unrelenting dispute between environmental concerns and public health needs.

Environmentalists and the state’s Department of Natural Resources have outlined several environmentally detrimental issues the hospital’s location would cause, while Horry County officials and the state’s Department of Health and Environmental Control say the facility would tackle rising public health needs. And, at the center is Conway Medical Center, which is reluctant to stray from its stalled plan.

Rising population means need

No one debates that as Horry County’s population continues to swell, another hospital is necessary to meet the county’s health care needs. It’s the main crux of Conway Medical Center’s argument for the facility’s location across from Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve.

CMC saw “significant need for (hospital) beds in our community,” Brian Argo, the center’s chief executive officer and president, said during an April community meeting. So CMC purchased the 353-acre tract for $5.5 million in 2021.

By 2040, the population in Conway East — a county census division — is predicted to climb to 185,000, according to a county document. It’s a nearly 92% increase from the 96,520 people who were living in the area in 2020.

In March 2021, DHEC agreed that the 50-bed hospital was necessary for the area, giving CMC’s plan state-issued approval. The hospital’s 50 beds would be transferred from CMC’s primary 210-bed facility in Conway, where they are under-utilized.

Earlier this year, the state Department of Health and Environmental Control granted approval for three more hospitals in Horry County — McLeod Health’s Carolina Forest hospital, Tidelands Health’s Carolina Bays hospital in Socastee, an expansion to Grand Strand Health’s South Strand Medical Center and a new tower at its Grand Strand Medical Center facility. The 48-bed McLeod hospital is within 2 miles of Conway Medical Center’s planned facility.

Not including CMC’s new facility that would be built near International Drive in Carolina Forest, the projects are expected to create nearly 200 new hospital beds in Horry County.

But one of the major barriers to CMC’s 50-bed hospital plan is an environmental argument against the proposed hospital location. The Coastal Conservation League and the state Department of Natural Resources say building the hospital along International Drive would affect the nature preserve. The hospital would be considered a smoke-sensitive area, a designation that would prevent burn managers from sending smoke in that direction.

Taking away a direction to send smoke would disrupt Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve’s distinct ecosystem, experts say. Because of this, the closer the burn site is to the hospital, the less vegetation can be burned. That could lead to a greater risk for wildfires.

Prescribed fire management and a medical facility are not compatible, state Department of Natural Resources Director Robert Boyles said in letters to the Horry County Planning and Zoning Department and the state’s Department of Health and Environmental Control.

Each year, the state DNR and state Forestry Commission burn at least 1,500 acres inside the 10,000-acre preserve. Masciarelli, the county councilman who opposes the hospital plan, said some years the state agencies conduct up to three burns.

Other locations are available to build the hospital, “but there is only one Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve,” Boyles wrote.

Besides addressing concerns about public health and the environment, CMC officials have tried to quell residents’ worries about increased noise and traffic. Hospital officials say that if the medical center isn’t built, a residential development of over 3,000 homes could go in its place, which will create more of the traffic and noise that residents so fear.

Between June and December, more than 23,000 people signed a petition to the medical center’s president and CEO urging CMC to find another location for the hospital. Conversely, more than 100 CMC health care professionals have backed the need for the $160 million project, according to documents filed with DHEC.

In the past three years of debate, CMC hasn’t budged. Recently, its spokesperson said because there are no new updates on the planned hospital, the center has no comment on the project.

Necessary to burn

The Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve’s ecosystem is dominated by woody, waxy vegetation and Carolina bays that promote habitats for everything from Venus flytraps to lumbering black bears.

But if the vegetation is not maintained with prescribed burns or those burns are restricted, it becomes “incredibly dense,” which increases the risk of wildfires, said retired Coastal Carolina University biology professor James Luken.

On April 22, 2009, a wildfire described by the South Carolina Forestry Commission as the state’s most devastating and costly — known as the Highway 31 fire — started near the preserve. It tore through Lewis Ocean Bay, more heavily affecting areas that had not recently gone under prescribed burns.

The preserve’s vegetation was fuel for the fire that ended up jumping over S.C. 22. It burned through 19,130 acres, with forested wetlands damage estimated costs around $17 million. The wildfire destroyed 76 homes and caused total damages of about $25 million.

Had the hospital been established at that time, it would’ve been affected by the smoke, the Coastal Conservation League said. At the very least, the league expected it would have been evacuated due to the proximity of the hospital to the fire.

Smoke impact

Environmentalists say it makes no sense to build a hospital to improve public health needs while locating it adjacent to an area that requires prescribed burns.

In South Carolina, smoke management guidelines say that prescribed burn managers cannot send smoke toward smoke-sensitive areas that are within 1,000 feet of the planned burn site. Trapper Fowler, North Coast project manager for the Coastal Conservation League, said smoke-sensitive areas include hospitals and schools. The league is a nonprofit that works to protect the health of South Carolina’s natural resources.

Despite efforts by burn managers to avoid sending smoke in the hospital’s direction, wind can’t be controlled. So smoke could still blow toward the hospital, said Fowler, who is a certified prescribed fire manager.

When prescribed burns are held at the preserve, gates close off access to International Drive because the smoke can hurt drivers’ visibility. Under current plans, the hospital would sit behind those gates, meaning access to medical care could be hindered during burns. Prescribed burns can smolder for a while, said Fowler, adding that in 2021 International Drive was shuttered for four days.

While smoke is a health hazard for any person, breathing it is particularly unhealthy for the elderly, children, pregnant women and those with lung or heart diseases. The plumes of smoke can cause stroke, asthma and heart attacks, according to the American Lung Association.

CMC spokesperson Allyson Floyd has said the facility would be equipped with a specialized HVAC system to keep out any smoke from a prescribed burn.

These types of specialized HVAC systems are a reasonable solution for maintaining indoor air quality during a prescribed burn, said Mary Johnson, a principal research scientist in environmental health at Harvard University.

To begin with, newer hospitals are more air tight inside, Johnson said. Because of that and strict regulations, a hospital would be an “efficient” organization to work with compared to a housing community, which is difficult to regulate, she added.

But the South Carolina Forestry Commission and Coastal Conservation League aren’t convinced a specialized system is enough to protect against the effects from smoke.

The specialized system that would be inside the hospital “only considers air inside the facility, and not in the surrounding area,” where people coming into the hospital could be affected by wildfire smoke, Darryl Jones, the commission’s forest protection chief, wrote in an April email.

Johnson said she wasn’t aware of studies that examined effects of very short-term smoke exposure such as a walk from a car to an entrance.

According to National Institutes of Health research, a small number of studies have been conducted of short-term smoke exposure, which is defined as exposure for up to a month. The studies showed short-term exposures were associated with increased risk of hospital admissions for neurological disorders and poorer performance on cognitive tests. However, impacts of smoke exposure lasting less than a day have not been studied adequately, according to Johnson.

Other options

To avoid development and its threat to prescribed burns, the state DNR offered to purchase the International Drive property from CMC to conserve it.

“We hope that you will consider this request to allow the first right of refusal should CMC decide to abandon the current site,” wrote Lorianne Riggin, DNR’s director of environmental programs, in a May 2022 email to Argo and Bret Barr, CMC’s then-CEO and president. Barr transitioned to a role on CMC’s Board of Trustees in December 2022.

Barr responded that the center’s plan had not changed. Currently, the land is appraised at around $7 million and remains zoned for residential use.

In September, Horry County Councilman Dennis DiSabato, whose district includes the proposed hospital’s site, said regardless of DNR’s offer, he doesn’t think the state agency has the ability to pay fair market value. And there’s nothing that would require the hospital to sell it for less than that, he added.

But Masciarelli, the county council member who opposes the proposed hospital site, said in August that whether DNR can afford the land is not the council’s concern.

As a local Realtor, he called the property “problematic” and “mosquito-ridden.” He said building near the preserve was akin to setting up shop near a nuclear reactor site. There’s a reason why “no one has touched the site with a 10-foot pole” while rapid development has gone up around it, Masciarelli said.

“You’re buying next to a preserve where they will potentially burn once, two, three times a year. It gets so bad and smoke-ridden,” Masciarelli said. “I just don’t know a builder that would invest millions of dollars with that kind of risk.”

He thinks neither a hospital nor a residential development should go in the plot.

DiSabato, who supports CMC’s plan over the potential construction of densely packed homes, said a hospital would generate less traffic and noise than a residential community, and it would fulfill health care needs in the growing county.

“The hospital will have no greater impact on prescribed burning than 3,232 multi-family housing would have on it,” CMC’s Argo said at an April community meeting. “So for us, we see this as a benefit to the community and a better alternative.”

A decision in limbo

Plans for CMC’s new hospital called for it to be finished by October 2023. But two months after the deadline, no earth has been turned. The delay has been caused by a separate issue involving another piece of county-owned property adjacent to the hospital site.

The county plans to use that site as part of its $600 million RIDE 3 road construction program. The county says RIDE 3 will destroy wetlands, which means county officials must protect wetlands elsewhere as part of credits for a mitigation bank. The county has targeted wetlands on the 3,700 acres it owns adjacent to the hospital site for the mitigation bank.

But that plan must get approval from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

As of Dec. 21, the proposed mitigation bank was “still under review” and “there isn’t any particular timeline for a decision,” said Glenn Jeffries, the Army Corps Charleston District’s chief of communications.

The holdup involves prescribed burns on those 3,700 acres. If the Army Corps of Engineers determines that the hospital construction will reduce the number of prescribed burns on that land, the amount of wetlands that can be set aside for the mitigation bank may be reduced. That could affect Ride 3.

The county council has held off giving final approval to a rezoning change for the hospital until it gets a decision from the Army Corps.

“Like Lewis Ocean Bay, it will also require frequent prescribed fires to release wetland credits, which is necessary to restore the habitat and reduce the risk of wildfires,” Coastal Conservation League’s Darienne Jordan wrote on the nonprofit’s website. “Limiting prescribed fires will mean a loss of potential mitigation credits and delays and higher costs for needed road improvements.”

To get all the wetland credits, more than 2,000 acres of the area would require prescribed burns in the first five years, the Coastal Conservation League’s Fowler said. The land, according to the Army Corps of Engineers, will need to be burned every few years in perpetuity. Currently, the land does not get prescribed burns.

Officials with the state DNR said the agency would “re-engage in conversations” over accepting long-term stewardship responsibility if the hospital goes elsewhere. With an already developing landscape, with subdivisions bordering three sides, a hospital would make prescribed burning difficult because it would limit where burn managers could send smoke. Riggin called it an “unknown challenge” in a letter to RIDE 3 Program Manager Jason Thompson.

Coastal Conservation League staff concluded that it would cost at least $400,000 to hire a contract burner every two years in perpetuity.

In an April 2021 email, Riggin said DNR would not be involved in any prescribed burns on the mitigation bank property if the hospital is built. But in a May 2023 email, Riggin told Thompson that DNR would “definitely reconsider” long-term stewardship of the mitigation bank if housing units were built instead of the hospital.

“There is concern over the liability associated with people experiencing medical emergencies that are trying to reach the hospital because the gates are closed,” Riggin wrote. “With a residential development, we are accustomed to notifying ahead of time with our typical outreach when burning season approaches and when prescribed burns are scheduled.”

The other option is to conserve the proposed hospital site — keeping it from being developed — which would “eliminate any additional burden regarding prescribed fire management planning and execution for both the County and SCDNR,” Riggin said.

Some Horry County Council members expressed concern that if the mitigation bank plan isn’t OK’d, the county wouldn’t get the credits it needed.

“Will development around our property decrease the number of credits we will receive?” County Administrator Steve Gosnell wrote in an August 2021 email to Thompson.

Thompson responded that assuming CMC built its facility, it would restrict the number of potential burn days, which in turn could reduce the number of acres burned and lower earned mitigation credits.

As a timeline for the council’s final reading for approval to rezone the 353-acre property by the council hangs in limbo, DiSabato said while he can’t be sure how other council members vote, it’s typical that they follow the lead of the district’s representative.

In this case, it’s DiSabato. And he wants the CMC facility.