Hear me out: why Coneheads isn’t a bad movie

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the summer of 1993, the Coneheads movie arrived with high expectations. Its producers had good reason to believe it could ride the coat-tails of one of the top grossing movies of the previous year, Wayne’s World, which pulled in over $180m worldwide. After all, both films translated beloved characters from the classic TV show Saturday Night Live to the widescreen world of Hollywood. More, SNL had enjoyed parallel success with its first attempt to move its franchise from small screen to big – The Blues Brothers. That 1980 film became one of the top-grossing hits of the year, going on to be recognized by the Library of Congress as a “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” work.

Related: Hear me out: why Johnny Mnemonic isn’t a bad movie

Things didn’t quite work out that way for the film adaptation of SNL’s pointy-headed aliens. The reviews compiled by Rotten Tomatoes summed up the screen version of these charming intergalactic creatures as “listless, crude and uninspired”. Roger Ebert went in a more alliterative direction, calling it “dismal, dreary and desperate”.

Small wonder Coneheads lost money in the US and wasn’t even released internationally in its day. That’s a baffling response considering the depth of the film’s themes, the variety of its subtexts and, crucially, the laugh-out-loud hilarity of its script. Far from a stretched-out exploitation of a TV bit, or an air-headed comedy, Coneheads had a socio-political resonance and a verbal inventiveness that, apparently, sailed right over the heads of what its title characters would call “the blunt skulls” (ie human beings). True, Coneheads was a harder sell than either Wayne’s World or The Blues Brothers. Both earlier films sent up character types we all know well – the suburban stoner teenagers in Wayne and the soul-music-loving baby boomers in The Blues Brothers. Coneheads asked more, challenging a host of our most basic assumptions, including our notions of beauty, our approach to “otherness”, our attachment to the American dream, as well as our most common expressions of prejudice.

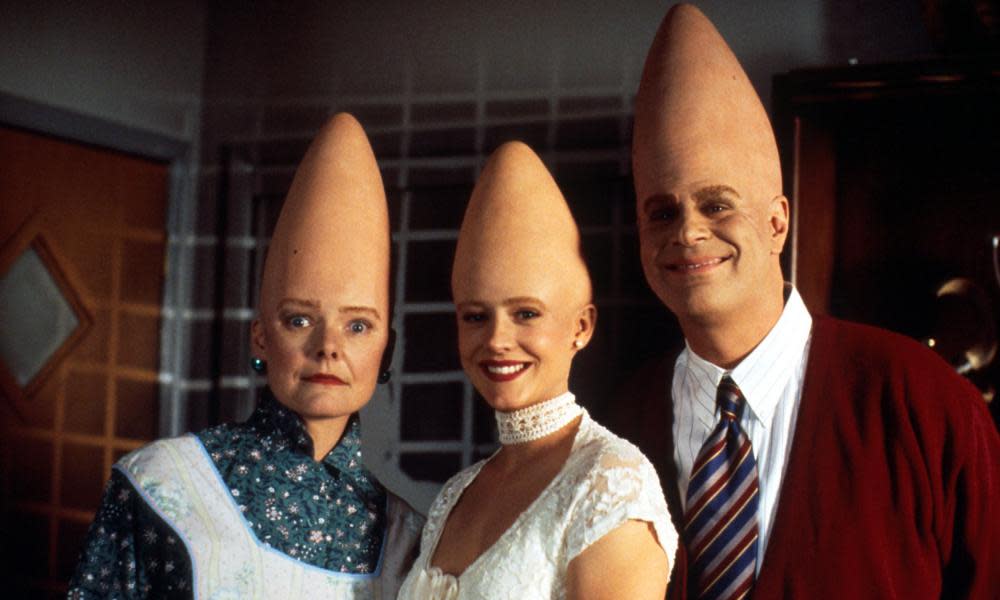

From its start, the film took on big targets. In an early scene, lead aliens Beldar and Prymaat Conehead (stupendously played by Dan Aykroyd and Jane Curtin) crash-land their space vehicle in Jersey City where they soon check into a local motel. Noticing the Bible in the drawer, Mrs Conehead starts reading, which instantly sends her into uncontrollable fits of laughter. As religious digs go, that’s right up there with Monty Python’s Life of Brian. The movie’s plot centers on two absurdities – the Coneheads’ attempts to integrate themselves into society and the machinations of a zealous immigration agent who wants to expel them as illegal aliens. (Only later does he discover that they are literal aliens.) The film’s immigration theme reflected the scriptwriters’ critique of the policies of then president Reagan, an attitude that would turn apoplectic were it to be updated to the days of Donald Trump. In fact, the INS agent in the film does Trump one better by proposing an electrified fence at the southern border primed to zap anyone who tries to enter the country.

Meanwhile, Beldar Conehead presents the most empathic portrayal of the immigrant imaginable. He’s incredibly hard-working, efficient and uncomplaining. As such, he earns the respect of the fellow strivers he meets in New York’s Black and south Asian communities. Beldar’s ambition allows his family to move to the suburbs, where they try to cover for their unusual appearance and behavior by claiming to come from France. The fact they get away with this howler smartly sends up American provincialism. Likewise, the way the Coneheads eat – “consuming mass quantities” in their parlance – presents a wry comment on American greed.

The Coneheads’ placement in the suburbs mirrors the setting of the original SNL skit. It was inspired by two popular American TV shows of the mid-1960s – The Addams Family and The Munsters. Each featured “freaky” characters who considered themselves entirely normal. Their confidence served as a cool rebuke to the Eisenhower era of Leave It to Beaver conformity while also presaging the “let-your-freak-flag-fly” ethos of the coming counterculture. The Coneheads’ parallel ability to assimilate into society while staying true to their eccentric identity likewise subverted the whole notion of “the outsider”. The most fascinating part is that, other than the ghastly INS folks, everyone who encounters the Coneheads accepts them entirely. It’s a perfect example of the disparity between the positive way most people treat outsiders they actually know and the negative way they are manipulated to regard them once they’re demonized as a threatening force by politicians and pundits.

If that sounds like heavy stuff for a comedy, the movie maintains its lightness through the delight of its language. Because the Coneheads understand no local idioms, they speak in hilariously tortured descriptions. They refer to lunch as “a midday cessation of activities for protein carbo intake” and cheese pizza as “a starch disc topped by the molten lactate extract of hooved animals”. The language they add from their home planet, like “torg”, “smordid” and “Lorpslap”, sound like drunk Swedish. Together, their perspective achieves the goal of the greatest satires – to present an alternate universe that lets us see our own more clearly.

Coneheads is available on Paramount Plus in the US and to rent digitally in the UK