This heart pump can be a better option than a transplant. But it’s not for everyone

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When a patient has severe heart failure, the heart isn’t strong enough to pump blood throughout the body.

A patient with severe heart failure may need a new heart from a donor to replace the bad heart. But waiting for a heart transplant can take months or years.

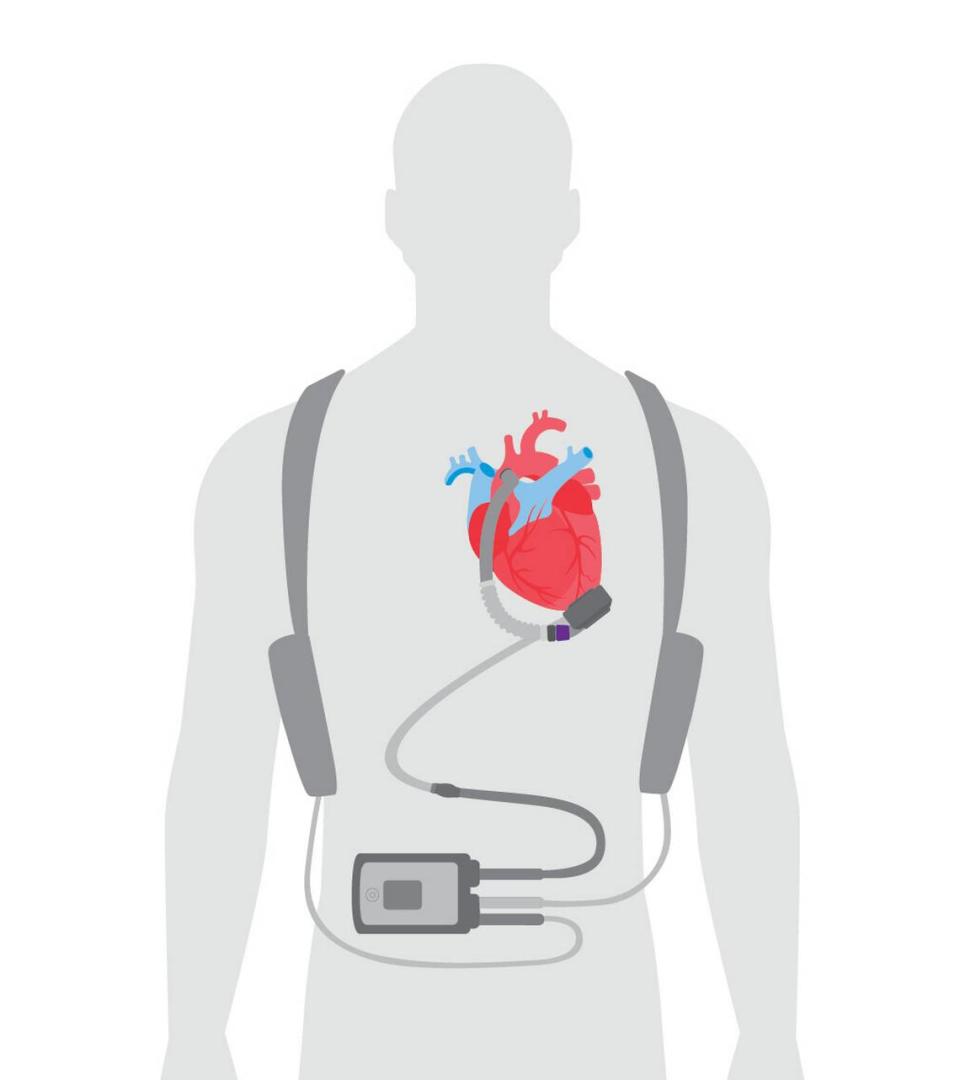

To keep that patient alive while awaiting the transplant, cardiologists and heart surgeons sometimes will recommend a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, a battery-operated, mechanical heart pump invented in the early 1970s that can be implanted at the bottom of the heart inside the chest.

A heart has four chambers: the right atrium and left atrium (the upper chambers), and the right and left ventricles (the lower chambers). The upper chambers — the right and left atria — receive incoming blood. The two lower chambers — the ventricles, which are more muscular — pump blood out of the heart.

The left ventricle is key — it is the heart’s main pumping chamber and pumps the blood into the aorta, a large artery that transports oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body, keeping the brain, liver, kidneys and other organs alive. The heart pump functions as the left ventricle, receiving blood and sending it to the rest of the body via the aorta.

But it’s not for everyone and it has risks.

Here’s what to know:

Who can and can’t get a heart pump device?

Heart pumps, like heart transplants, are considered the last resort for people with end-stage heart failure. Doctors will consider heart pumps only for people with failing hearts who have tried everything else, such as medications, lifestyle changes and other heart procedures, such as valve replacement surgery.

“For a patient to receive an LVAD, they need to have a heart sick enough to need one, but must not be too sick overall — otherwise the LVAD is too risky,” according to Stanford Medicine, part of Stanford University.

Some factors a physician will consider when deciding if you’re a good candidate for a heart pump, according to the Mayo Clinic and Penn Medicine:

▪ The severity of your heart failure. There are four stages of heart failure — at high risk, heart disease without signs of heart failure, heart disease with signs of heart failure and heart failure not responding to treatments.

▪ How serious your other medical conditions are

▪ Whether you can take blood thinners safely

▪ Your mental health and ability to take care of the device

More than 2,500 people with heart failure have a heart pump implanted in their chest annually in the United States.

Sometimes, patients get a pump to help keep them alive while they wait for a new heart. In fact, heart pumps are sometimes called “bridge-to- transplant” devices.

But doctors may recommend a heart pump for patients who aren’t considered to be good candidates for a heart transplant. This could be due to age or other conditions, such as diabetes, or whether the patient has or recently had cancer and is not considered to be cured, said Dr. Cedric Sheffield, surgical director of the heart transplant and mechanical circulatory system at Cleveland Clinic Weston.

In some cases, the heart pump may be able to restore the heart’s function, eliminating the need for a transplant. Sheffield said patients, on average, can live up to seven years with a pump, though he’s had patients who’ve lived 17 or 18 years more with the device.

About 91% of heart pump patients at Cleveland Clinic Weston survive a year after the implant, compared to 84% nationally, according to data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“We’re in a heart failure epidemic in this country and we have been for a long time and will be in the foreseeable future,” Sheffield said.

What are the risks?

While a heart pump can help someone with a weak heart stay alive, the device does come with some serious risks, including blood clots, right heart failure, device malfunctions, bleeding and infection, according to the Mayo Clinic.

“A blood clot from a VAD can slow or block blood flow, causing stroke, heart attack or problems with the device,” the Mayo Clinic said.

A heart pump can also lead to infections “because the power source and control unit for your VAD are located outside your body and are connected through a wire ‘line’ through a small opening [port] in your skin,” increasing the risk of germs getting into the area,” the Mayo Clinic added.

Strokes, too, can be a complication, along with damage to blood cells due to the pump, according to Stanford Medicine.

How does the procedure work? What’s the recovery time? Survival rate?

The patient would undergo open-heart surgery to get the mechanical pump implanted in their chest. The patient will then stay two to five days in the intensive care unit in the hospital before being transferred to a regular hospital floor, Sheffield said.

In total, the patient can expect to stay in the hospital for 10 to 14 days, though this will vary depending on each person’s individual health.

By two months, most patients have recovered from the surgery. They’ll also have to schedule weekly follow-up visits, initially. Eventually, they’ll have check-ups every few months.

How does this affect your life? Diet? Things you can and cannot do?

“The goal is to prolong your life. The other is to normalize the quality of life. And to sustain both of those goals for as long as possible,” Sheffield said.

Once recovered from heart pump surgery, a person can go back to their normal life, for the most part. They can walk, work, have sex, shower (the hospital will teach them the proper procedure) and travel, with minor accommodations, according to Sheffield and Stanford Medicine.

What they can’t do: “LVAD patients cannot swim, play contact sports, or be away from a source of electrical power,” Stanford Medicine said.