'Heart of a small town': Thomaston dreams of converting historic school into lively community hub

When Connie Willamor steps out onto her big white house’s front porch in Thomaston, Alabama, she can see a few things.

First, she sees the old gymnasium, the one that underwent about $1 million in renovations to become Dave’s Market. Further to the right, she sees the Rural Heritage Center, which closed earlier this year after nearly 17 years in operation.

In the middle sits her largest neighbor: the old Marengo County High School. Built in 1909 and shut down in 1979 amid forced integration efforts in Alabama, the building is significant enough to be on the National Register of Historic Places.

The peeling white paint, rows of shattered windows, and overgrown lawn won’t tell you that, though.

Since buying her house across the street in 2012, Willamor has looked at the building thinking about all of its potential. The county deeded the school building to the City of Thomaston years ago, so Willamor would bring up her ideas to city employees now and again.

“As small as we are, we don’t have the money or the resources to refurbish it or do anything,” Thomaston Mayor Rudy Parker said.

Last year, Willamor decided to stop waiting for someone else to fix it.

DEFINING THE BLACK BELT: How the expansive region shaped Alabama history

'ART IS A CATALYST': Foundation devotes over $62k to rural arts across Black Belt

The rise and fall of a community marketplace

Openings and closings happen on the regular in Thomaston. For a Black Belt town of about 400 people, an outsider might be surprised by the amount of business turnover there.

Until the pandemic, the old high school gymnasium was home to Dave's Market. To reach it, people walked from across the block or drove farther away in their golf carts to stroll the aisles set atop what was once a basketball court. Hoops remained mounted to the walls at either end. Shoppers passed under them as they bought groceries for dinner — some fresh vegetables or whatever fruit was in season.

Now, though, Dave’s lights are turned off. Shelves are empty. Locals drive miles out of town for groceries instead of walking across the street. If you look closely into the tinted windows, you can still see a row of shopping carts lined up in their pen.

“It was wonderful, and sometimes when things are wonderful, they go south because somebody else wants it,” Mayor Parker said. “Dave had a heck of a business. It was thriving, and people from surrounding counties came to Thomaston.”

It was the only grocery store in town, but the business didn’t survive a change in ownership. The town remains hopeful that Dave’s will make its great return sometime soon.

The market isn’t the only closure Thomaston has seen in recent years. Visible from across the old Marengo County High School campus is the skeleton of a quaint lunch restaurant called the Pepper Patch. It served pimento cheese sandwiches, po’boys and daily specials until it closed “for infrastructure reasons,” according to local business owner Hale Smith.

Smith grew up down the road in Linden, but he is a lifelong resident of Marengo County. After living in Thomaston for over two decades, he said it’s easy to notice a pattern in rural economies.

“The businesses have kind of been up and down in our little town, like most small towns in the Black Belt,” Smith said. “We don't have a lot of schools in the area. Many people have moved to cities and moved out of town — younger families have, anyway. But we've had some positive things. We’ve got the land company, and we got the feed store there. We got a little rural medical center there now.”

The unpredictability that comes with investing in a rural community means that, oftentimes, investors aren’t just in it for the money. They’re in it for the people.

That’s why Willamor spends time, money and energy in Thomaston — and she’s hoping that it will pay off any day now.

Wishes and watermelons

Willamor created the Thomaston Historical Foundation in May 2021 and decided she would find a way to restore the old building, working with the city for access and her own time and money for resources.

First, she paid a general contractor to inspect the school building. The contractor said she needed to get rid of a termite infestation and pay for a termite bond, both of which she did. From there, she brought in a foundation contractor to inspect the school's largest room, the auditorium.

Cobwebs, debris and a drooping floor distract from the room’s tall vaulted ceiling and window-lined walls. Willamor has envisioned community meetings, holiday pageants and local theater productions filling the space. In reality, the mayor hardly lets anyone inside the building because of “liability reasons.”

Between the contracting, termite treatment and other supplies, Willamor has invested thousands of dollars into the project thus far.

“Oh, I don’t know, at least a couple thousand,” Willamor said. “I don’t really keep up with the price of all of it because it’s fun, and it’s important to me.”

In her quest to get the building back up in working shape, Willamor received two partial estimates. The cost to fix the corners of the school where the foundation is falling in will be about $68,000, she said, and to fix the concave floor in the auditorium will cost closer to $90,000.

That makes about $158,000 in foundation work alone, not to mention repairing the windows and general cleanup. In the classrooms below the auditorium, Willamor’s contractor told her, there are about 2 inches of standing dirt and mud caked to the floors.

It’s a tall order, but one she’s confident will be delivered.

“I'm just attached to it, and I want to see it redone. I know once I get word out there that we’re refurbishing it, and I get word out there that it can be used, people will want to help,” Willamor said, “I've got to pull money from somewhere to get things started.”

One way she has taken to raising money and awareness for the project is by starting the Watermelon Festival in town, held in front of the old high school on the last Saturday of June. This year's event from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. on June 25 will be the second annual.

So far, Willamor has secured 30 vendors who will sell baked goods and homemade items for the 2022 festival.

With each vendor paying a $40 fee to set up a booth, she’ll make back just enough money to pay for the 200 watermelons that her husband will drive up from their other home in Mobile. Beyond that, Willamor hopes T-shirt sales and donations to the Thomaston Historical Foundation will go toward the actual restoration project.

Community feelings

Parker, the town's mayor, graduated from the high school in the class of 1970 as pressures to integrate the public schools in the area intensified. That was the beginning of the end for the school as many white families in town began to send their children to private schools.

The mayor has plenty of favorite memories in the old high school building. “But I can’t tell you,” he said. “It was a great place.”

For a few years after the school closed, Parker said the town did have meetings and small events there, just like those Willamor envisions, but they didn’t last long.

“Everybody would like to see it restored, but nobody wants to pay for it,” he said. “Schools and churches are the heart of a small town. If you don’t have a school, small towns die because people rally around schools. So when the school left, the town didn’t die, but there just wasn’t as much there.”

The only school left in Thomaston is Amelia Love Johnson High School, with a student body that is 99.4% Black and 99.4% economically disadvantaged.

'Art is a catalyst': Foundation devotes over $62k to rural arts across Black Belt

'Communities that made them': Alabama-born business owner reinvests in the South

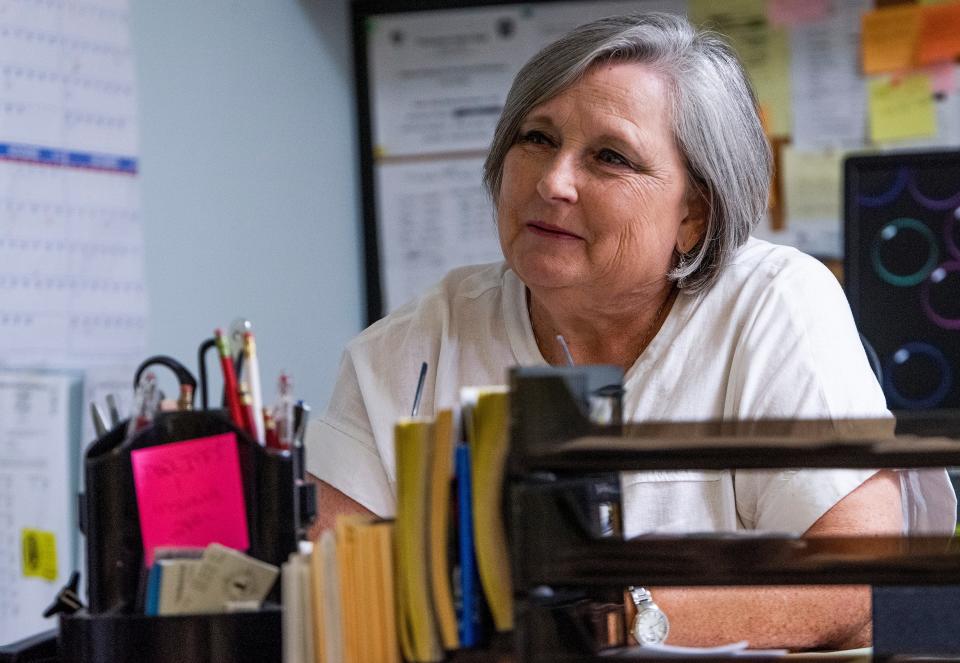

“There’s no whites that go there. They could, though,” Town Office Clerk Donna Stokes said. “Our churches are struggling to hang on, too. It’s the domino effect of everything.”

She said she wouldn’t live anywhere else in the world.

Al Moseley, the owner of one of Thomaston’s long-standing businesses, agreed. He’s lived there his whole life and graduated from the old high school in 1972. Now he operates the feed store downtown, one of the few storefronts left there besides the Whitetail Museum and the mayor’s pecan shop.

Moseley remains skeptical about the feasibility of fixing up his old school.

“What is it going to take to fix that thing? I don’t have any idea, but I know it’s in bad shape,” he said.

Moseley is like many others in town, though, in that he appreciates Willamor’s gumption.

Willamor's timeline

Willamor said there’s no telling when she’ll reach her final goal, but she knows she will.

For now, she’s just looking forward to the last Saturday of this month when she’ll welcome a crowd onto the old high school grounds for the Watermelon Festival.

“That’s what it’s about," she said. "Having fun and then making money.”

Hadley Hitson covers the rural South for the Montgomery Advertiser and Report for America. She can be reached at hhitson@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Thomaston Watermelon Festival aims to restore glory of old high school