Helen Gurley Brown’s ‘Daughter’ on the Cosmo Editor’s Legacy, #MeToo, and Anita Hill

Just two years before she died at the age of 90, Helen Gurley Brown was tap-dancing in her New York penthouse, waiting for the elevator.

Brown’s husband, Jaws producer and former Cosmopolitan managing editor David Brown, had just died. And she didn’t want to be alone.

“As we’re waiting for the elevator, she starts singing and tap-dancing to ‘I love you, a bushel and a peck,’” her longtime friend, writer Lois Cahall, told The Daily Beast. “She doesn’t want me to go, so she’s trying to stay humorous and adorable. We stepped in, and this very handsome guy in workout clothes comes onto the elevator.”

“She scanned him up and down and said: ‘We have delicious men living in this building, don’t we?’”

Even in her late eighties, Cahall said, “Everything was sexual.”

The famous Brown, who died in 2012, was best known for writing the 1962 bestselling guide to single womanhood Sex and the Single Girl before she took the helm of Cosmopolitan as the magazine’s first female editor.

Brown—who called herself a “mouseburger” and everyone else “pussycat”—served as editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan from from 1965 until 1997, from her boudoir-like corner office outfitted with leopard print rugs, floral couches, frilly curtains, and a tiny chair from which she would hold court.

She also accumulated 178 lovers before she was married.

Cahall, who met Brown in the 1980s, eventually came to see her as a second mother.

“After interviewing for a job in New York one day, I ended up that night celebrating on the balcony at Studio 54, and later dancing with Chevy Chase,” Cahall said. “Helen sat nearby in her leopard pumps and micro-mini skirt. She was like my corny pioneer, cheering me on with a shared sense of enthusiasm.”

The two struck up a friendship that lasted decades.

“I began to channel her as my mentor, my friend, and eventually my new mother. And she let me,” Cahall said. “What started out as ‘Dear Mrs. Brown…’ turned to ‘Dear Helen’ and finally ‘Mommy Helen.’”

HELEN BECOMES FICTION

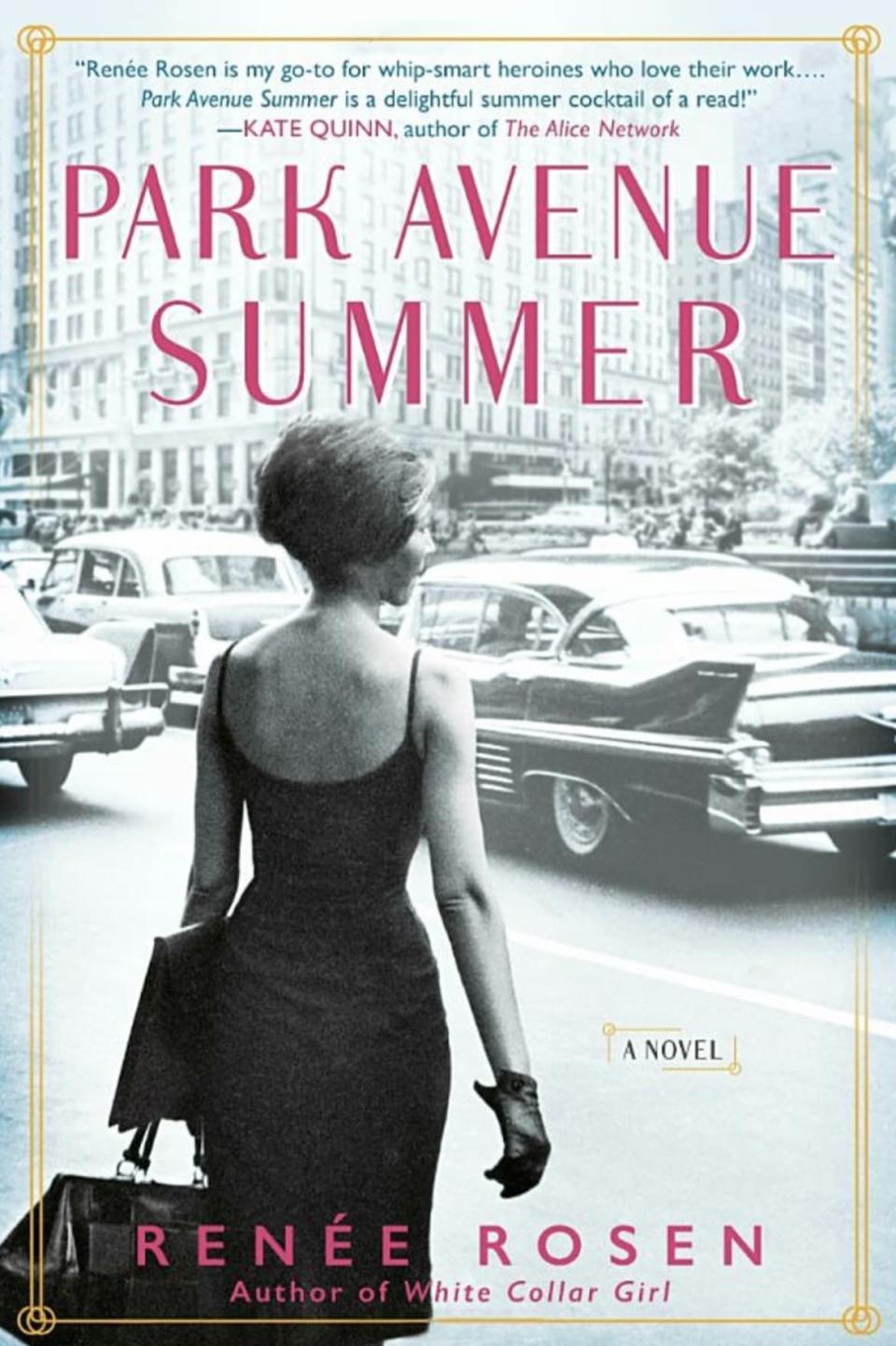

Cahall and Brown’s relationship helped inform the forthcoming novel Park Avenue Summer by Renée Rosen, which will publish next week on April 30. The book is a charming dive into 1965 Manhattan, when Brown took over Cosmo and changed it forever.

The book’s fictional heroine, Alice Weiss, lands a job as Brown’s secretary and helps the idiosyncratic character dodge several schemes to sabotage the magazine—all while dating men, attending glamorous dinners, and pursuing her dream to become a professional photographer.

Rosen said Cahall’s influence on the book changed it for the better, and kept Brown’s character from becoming a caricature.

At first, Cahall said, Rosen had written Brown as an Anna Wintour-esque editor.

But Brown wasn’t like that at all.

“She really, she wanted to put people at ease,” Rosen told The Daily Beast. “Within five minutes of meeting her, she’d tell you she was wearing a padded bra, fake eyelashes, and a wig. She didn’t want anyone to be intimidated. She had that doll’s chair, a little tiny chair smaller than everything else in her office. She would hold court there.”

In Brooke Hauser’s biography of Brown called Enter Helen, she wrote that the editor-in-chief’s “insecurity was cellular” and a guidepost for how she treated other people.

“She wanted everyone to feel like they were on a level playing field,” Rosen said.

Cahall described her as an affectionate woman covered in red lipstick (“on her lips, on her teeth, on her cheeks”).

“We always kissed full-front on the lips,” said Cahall, and Brown often made sexual comments to her college-aged daughter: “Do you know you have a beautiful bosom, pussycat?”

“She was persuading me all the time: Worship the penis. Worship the penis,” Cahall added.

Brown has been endlessly described as “whispery” and intentional in her flirtations.

“Everything had a reason,” said Cahall.

“Helen was always two steps ahead of everyone else in the room,” said Rosen. “She would just sort-of steer the conversation that way, without anybody else realizing it. She always made sure she got what she wanted.”

“Lois kept me more honest and more faithful to Helen’s true character,” Rosen said, noting that she felt like she was getting to know both women—whom she called “girls’ girls”—at the same time.

HAVING IT ALL

“There is a catch to achieving single bliss,” Brown wrote in Sex and the Single Girl. “You have to work like a son of a bitch.”

And so she did.

In addition to her reign over Cosmo, she published at least nine other books, including Sex and the Office (1964), Outrageous Opinions of Helen Gurley Brown (1967), Helen Gurley Brown’s Single Girl’s Cookbook (1969), Sex and the New Single Girl (1970), Having It All (1982), The Late Show (1993), The Writer’s Rules: The Power of Positive Prose (1998), I’m Wild Again (2000), and Dear Pussycat (2004).

Despite the books, the statement jewelry, and the iconic red lips, Brown was a gentle and demure figure when she was at home, Cahall said.

Brown was born Helen Marie Gurley on Feb. 18, 1922 in Green Forest, Arkansas, and her father was a school teacher. Brown’s father died when she was only 10 years old, and shortly afterward her sister was diagnosed with polio. She lived in a trailer park.

“I never liked the looks of the life that was programmed for me—ordinary, hillbilly and poor—and I repudiated it from the time I was 7 years old,” Brown wrote in Having It All.

“We both came from the trenches, the lower classes. Her from her trailer park, me from my Armenian immigrant family,” Cahall said. “We never lost sight of where we came from.”

Brown wrote hundreds of letters to Cahall over the years, including one dated September 12, 2003, a few days after a dinner at Cahall’s home: “You are an exceedingly good cook and thoughtful child though I would rather be your girlfriend... I never wanted a child—no time or inclination to raise one though you seem to have taken care of that detail! You are wonderful to have supplied such joy (as in being a good cook and a good child.) All my love and thanks, Helen.”

“Helen was brave by nature, and taught the women who worked for her by example,” Jill Herzig, formerly editor in chief of Redbook (and now director of content innovation at Weight Watchers), told The New York Times in 2012. “When example wasn’t enough, she had no problem telling you, Oh come on—be gutsy. I did as I was told.”

But as much as Brown cheered on other women, she doled out advice that even Rosen admits appears “atrocious” in retrospect.

“Whether her work helped or hindered the cause of women’s liberation has been publicly debated for decades,” The New York Times wrote in Brown’s obituary. “It will doubtless be debated long after her death.”

Several passages of Sex and the Single Girl wouldn’t hold up to the scrutiny of the #MeToo movement. But even decades later, in 1991, Brown penned a Wall Street Journal column in which she criticized Anita Hill's charges against then-U.S. Judge Clarence Thomas. Brown wrote that “a little sexual tension in the office never hurt anyone.”

“Some girls ‘hate’ men because they secretly envy their superior advantages, their jobs, their ability to exploit,” Brown claimed in Sex and the Single Girl. “Get it straight in your head that anyone who wants to kiss you or sleep with you isn’t handing you a mortal insult but paying you a compliment. Oh, I know some men proffer their kisses and propositions with all the finesse of an invading army.”

In another chapter, she counsels that young women find men in their offices, even if “your company frowns on intramural dating.”

“Date anyway,” she wrote. “You will undoubtedly be fired, but imagine leaving under such a romantic cloud... a woman so attractive to and attracted by the opposite sex, she was willing to collect her unemployment insurance for them!”

Some of her other advice is bizarre—but impossible to ignore: In her 1982 book Having It All, Brown suggests that a woman may connect with a man by taking a strand of pubic hair, having it encased in plastic, and making it into a paperweight for his desk.

Had she lived to see 2017, Cahall said that Brown’s feelings about the #MeToo movement likely would have been complicated.

She was “a creature of sex and pleasing men,” Cahall said. “It was the way her mind was wired—and really, would we have wanted her to be any other way?”

“She created her own movement in the 60s,” Cahall continued. “I think she would have been surprised by today’s #Metoo movement, and proud of them, but I don’t think she would have been a fan of how the #MeToo is diluting their cause over every single issue. Can men no longer flirt with women? That’s probably how Helen would have seen it.”

Ultimately, Rosen believes Brown’s most important message is: “Make your life full. Make your life interesting. The men will come.”

“She had an instinct for what women needed in that time in history, and she gave it to them,” Rosen said. “There’s a generation of readers that may have heard the name but have no idea who she really was. I’m really excited about the opportunity to introduce this feminist icon, who had more impact on our lives than many people realize.”

“I’m really excited for new readers to discover Helen Gurley Brown.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here