Help arrives as rural Iowa insurers face an emergency. But their rescuer bears baggage.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

First of three parts

While an international insurance executive with a checkered past waited for access to Iowans’ money, the state’s insurance regulators opened the door.

“Urgent,” Iowa Insurance Division legislative liaison Chance McElhaney wrote in a Feb. 17 email to Sen. Waylon Brown, R-Osage, and Rep. Shannon Lundgren, R-Peosta, chairs of the House and Senate commerce committees. “Bill needed.”

The regulators were pushing for legislation to save Heartland Mutual Insurance Association, a small, 136-year-old firm in Algona. Company directors had recently learned that their firm would lose reinsurance ― a form of coverage for insurers to unload risk.

This reinsurance was vital, a legal requirement for the small farm mutuals that accent rural Main Streets across the Midwest. Without reinsurance, many of them would close.

Farm mutuals like Heartland are property and casualty providers that cover small territories. Like Heartland, the firms often date to the 1800s, when farmers pooled money to insure against the cost of rebuilding burned-down homes. They became particularly popular in Iowa, Illinois and Wisconsin in the late 1800s. The mutuals were a symbol of local control, a way to keep money in small towns instead of sending premiums to big, East Coast companies.

Today, the mutuals subsist as a remnant of rural tradition: Farmers buy coverage from the same firms their parents and grandparents did. A town's prominent residents sit on the board.

Legally, most of Iowa's 76 mutuals can sell policies only in tight geographic regions ― their home counties and surrounding counties. Their risk is concentrated. A single bad storm could devastate a mutual.

As a result, Iowa law requires them to buy generous reinsurance coverage to offset their higher level of risk. The mutuals must find companies willing to cover most of the claims during a bad year. The state law does not allow reinsurance firms to cap annual claims, meaning they could pay tens of millions for a single storm.

Reinsurers, with their broader base, try to balance that risk across many clients. But lately, following expensive derechos in 2020 and 2021, Iowa's uncapped claims provision has driven reinsurers away from the state. Other Midwestern mutuals suffer similar problems.

At Heartland, CEO Jared Carlson received a call from a representative of Wisconsin Reinsurance Corp. in June 2022, informing him that the company was dropping coverage. Wisconsin Reinsurance has since gone into liquidation.

Carlson said the two other companies that reinsured Iowa’s mutuals last year declined to sell Heartland coverage.

“It was stressful,” he said. “You have employees. You didn’t want to see them lose their jobs and their careers. You don’t want to see a company that is 136 years old going out of business. There just wasn’t a lot of options out there.”

As Iowa Insurance Division steps in, a rescuer emerges

With Heartland unable to secure the legally required coverage, the Iowa Insurance Division in December 2022 placed the firm in a status known as rehabilitation. The state would take over Heartland and wind up the business, returning premiums to policyholders and selling assets to pay off debts.

The Insurance Division received panicked emails. A customer asked why he was losing coverage. A Heartland board member asked how he could have prevented the failure. A longtime insurance agent said she worried there was no future in the business for her sons.

About two weeks later, a savior emerged. Executives at Indiana-based Mutual Underwriters met with Heartland’s board on Jan. 17 and offered to manage the firm. They said a sister company would sell Heartland reinsurance.

There was a catch: Mutual Underwriters wanted seats on Heartland’s board, which was illegal in Iowa because the management firm was not a policyholder. Insurance regulators mobilized to change the law, lobbying not only lawmakers but Gov. Kim Reynolds' office.

Jim Armstrong, Heartland's special deputy rehabilitator, asked Iowa Insurance Division Deputy Commissioner Kim Cross in a Feb. 11 email if a law change could be effective "when she signs it," a reference to Reynolds. Cross responded that McElhaney and Insurance Commissioner Doug Ommen understood "the importance of timing." She added that McElhaney was "following up to make sure igov folks understand," a second reference to the governor.

“Just got approval from IGov,” McElhaney wrote in a mid-February email.

McElhaney sent more emails to Commerce Committee members on Feb. 21 and 22. On March 14, the House passed the legislation, 97-0.

The bill would give Mutual Underwriters’ leaders what they wanted. But the legislation stalled in the Senate for more than a month.

On April 20, McElhaney emailed Sen. Carrie Koelker, R-Dyersville, asking her to carry the bill “over the finish line.”

“We really need it,” he wrote.

Koelker presented the bill on the floor, and the Senate passed the legislation, 48-0, on May 3. Reynolds signed the bill June 1.

A judge then approved a plan from the Insurance Division, ending Heartland’s rehabilitation and approving a seven-year contract between the Algona firm and Mutual Underwriters. The leaders at Mutual Underwriters would manage the company in exchange for 15% of Heartland’s premiums ― a rate that would have netted about $760,000 in 2022.

Newpoint Reinsurance, a firm in the Caribbean island of St. Kitts and Nevis, would provide reinsurance to Heartland. As part of the agreement, the Iowa company would turn over a portion of its premiums to Newpoint Reinsurance every month.

Carlson, the Heartland CEO, said the Insurance Division examined Mutual Underwriters and Newpoint Reinsurance, to make sure policyholders would be protected. That would be important, as Mutual Underwriters could become a bigger player in Iowa insurance in 2024 as other firms scramble for coverage.

In July, West Des Moines-based Farmers Mutual Hail Insurance Co. announced that it would exit the mutual reinsurance line of business at the end of the year. Its departure, along with Wisconsin Reinsurance's liquidation, left one traditional provider: Grinnell Mutual.

Launched by the Iowa Mutual Association in 1909 to provide reinsurance, Grinnell Mutual "may have been the first company of its kind for farmers in the nation," according to historian Jack Lufkin. But leaders at Grinnell Mutual, too, are shrinking their reinsurance business.

The company informed some mutuals this year that they will not renew policies in 2024. All told, leaders at 17 of the state's 76 mutuals learned in 2023 that they are losing reinsurance, jeopardizing their ability to operate when their current contracts expire at the end of December.

Some are still scrambling to find coverage, and Mutual Underwriters presents itself as one of the few available options.

“The state did due diligence,” Carlson said of Mutual Underwriters. “They did their research. They made sure everyone is OK.”

In an email to the Register on Dec. 12, McElhaney said the Iowa Insurance Division reviewed an agreement between Mutual Underwriters and Mid-Hudson Cooperative Insurance, a small New York company that is acting as Newpoint Reinsurance's fronting company. Under the arrangement, Mid-Hudson passes Heartland's revenue along to Newpoint Reinsurance, according to an Insurance Division court filing.

Mid-Hudson, which earns a profit for the agreement but could have to pay claims if Newpoint Reinsurance doesn't, has put money in a trust that complies with Iowa regulations, McElhaney said.

However, Mid-Hudson's CEO told the Register that his company will stop being a front for Newpoint Reinsurance at the end of this year, leaving uncertain whether another U.S. company will provide a similar service for the Caribbean firm.

McElhaney, meanwhile, declined to answer the Register's questions about an important player in the business arrangement: Keith David Beekmeyer, Newpoint Reinsurance's London-based executive. In addition to the Nevis company, Beekmeyer operates a web of businesses that stretch from the United Kingdom to Switzerland to California, a Register investigation found.

Company and court records also reveal that Beekmeyer has led multiple companies into liquidation, has been accused of fraud by former business partners, was arrested in Kenya on charges of forging paperwork, was blocked by the Bermuda Monetary Authority from buying an insurance firm, and worked for a Belgian company during the time that ― according to one investigator ― it perpetrated “the granddaddy of insurance frauds.”

Who is Keith David Beekmeyer, who's associated with the firm seeking to reinsure Iowa mutuals?

The early biography of Beekmeyer, 60, is hard to track. According to Michael Reeve, a former Beekmeyer boss, and Alex Woolgar, one of his former business partners, he is Sri Lankan and grew up on London’s East End, a region of the city known for its pockets of poverty and immigrant neighborhoods.

Short and rotund, Beekmeyer has told people that he quit school as a teenager to work in the mailroom of a bank, his former business partner said. There, Beekmeyer’s gift for numbers supposedly impressed the bank’s traders, who hired him to deliver messages as a runner. He worked his way up through London’s financial sector as he got older, the former business partner was told.

Beekmeyer declined an interview request, telling the Register in an email, "You are at liberty to write whatever you wish to write so longs (sic) as it is based on facts not misinformation hearsay or innuendo."

A July 1998 news release from one of Beekmeyer's companies said he attended the London Business School. A corporate biography, published a month later, said he received a bachelor’s degree from the institution, though a spokesperson for the school told the Register it has no record of an alumnus by the name of Keith David Beekmeyer.

Various news releases from Beekmeyer-backed companies and a corporate filing also state he managed a foundation’s property portfolio, worked for an oil company, brokered “international clients’ business” for the investment bank Barclays and gained 19 years of experience as an insurance broker ― all by the age of 36.

Such a biography would come as a surprise to Reeve, a London insurance executive who hired Beekmeyer in the early 1990s at the Belgian firm Dai Ichi Kyoto Reinsurance. He said Beekmeyer worked for him as a claims adjuster, a low-level employee who handled customer calls.

“He did the job capably, what he was supposed to do,” Reeve recalled to the Register. “But he always ― he was ambitious."

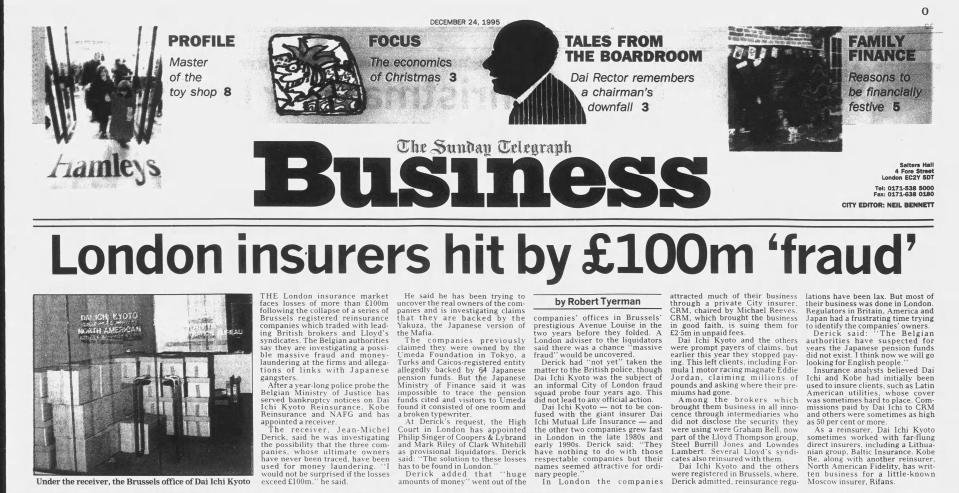

Beekmeyer was one of about 20 employees in Dai Ichi Kyoto’s London office, which Reeve managed. By the time Beekmeyer joined the firm, investigators had publicly flagged suspicious activity within the company.

A Tokyo group called the Umeda Foundation set up Dai Ichi Kyoto in 1989, claiming a balance sheet with about $282 million in assets from Japanese pension funds. But regulators could not identify the executives and investors behind the foundation, court filings show.

The company’s leaders did not publicly promote the business, instead issuing orders to managers like Reeve through faxes and phone calls. Reeve said he agreed to manage the firm’s London office after randomly meeting a representative of the Japanese investors in a Chicago bar.

Corporate paperwork identified a trio of companies set up in Delaware as Dai Ichi Kyoto shareholders. But those companies weren't established until after Dai Ichi Kyoto began to operate.

Roger Needham, a retired Delaware insurance investigator who looked into the shareholding companies in his state, recalled that the audits for those businesses looked fake. He knew one of the auditors whose signature was on the paperwork.

“I step in to see the guy,” Needham told the Register. “He said, ‘I didn’t certify jack (expletive).’ He didn’t know anything about it.”

According to a 1991 article in London’s Daily Telegraph, the Japanese minister of finance told the U.S. National Association of Insurance Commissioners that his office couldn’t find any record of the pension funds supposedly backing Dai Ichi Kyoto. A spokesperson for the accounting firm Coopers & Lybrand told the paper that its auditors quit working with Dai Ichi Kyoto after the company failed to produce requested information.

Despite the well-publicized concern, Dai Ichi Kyoto continued operating until a prominent client complained. Eddie Jordan, a Formula One team owner, sued the company in 1994 after the firm failed to pay an insurance claim that was supposed to cover employee bonuses if his team finished in the top six that year. (The team, Jordan Hart, finished fifth.) The Register could not locate records specifying the final resolution of the case.

Dai Ichi Kyoto quickly fell apart from there, and Belgian authorities served the company with bankruptcy paperwork a year later. Belgian investigators and FBI agents said they uncovered a complex web, with a small group of businessmen operating insurance firms, investment firms, money managers, shell companies and reinsurance businesses.

“I would not be surprised if the losses exceed 100 million pounds,” Jean Michel Derrick, a Belgian administrator appointed to oversee the bankrupt reinsurance businesses, told the Telegraph in December 1995.

In Delaware, federal prosecutors indicted two men they believed were at the heart of the fraud, writing in a court filing that investigators tracked $7.5 million in money transfers from Bermuda to Delaware to Tokyo to Belgium "in furtherance of a scheme to defraud companies that purchased reinsurance." Following those transfers, prosecutors said, the reinsurance firm failed to pay $3.3 million in claims tied to a California earthquake.

In Belgium, investigators said in a court filing that they tracked money transfers from Dai Ichi Kyoto and two sister reinsurance firms from 1990 to 1995. Though exchange rates fluctuate, the investigators said the three companies moved funds that would now be worth from $83 million to $116 million to shell companies.

According to investigators, couriers withdrew money from a bank and delivered cash to the reinsurance companies’ shared office in Antwerp, Belgium. Employees kept the money in a safe. Another courier would then pick up the money, which investigators say they traced to a villa in Cap Ferret, a luxurious vacation destination in the south of France.

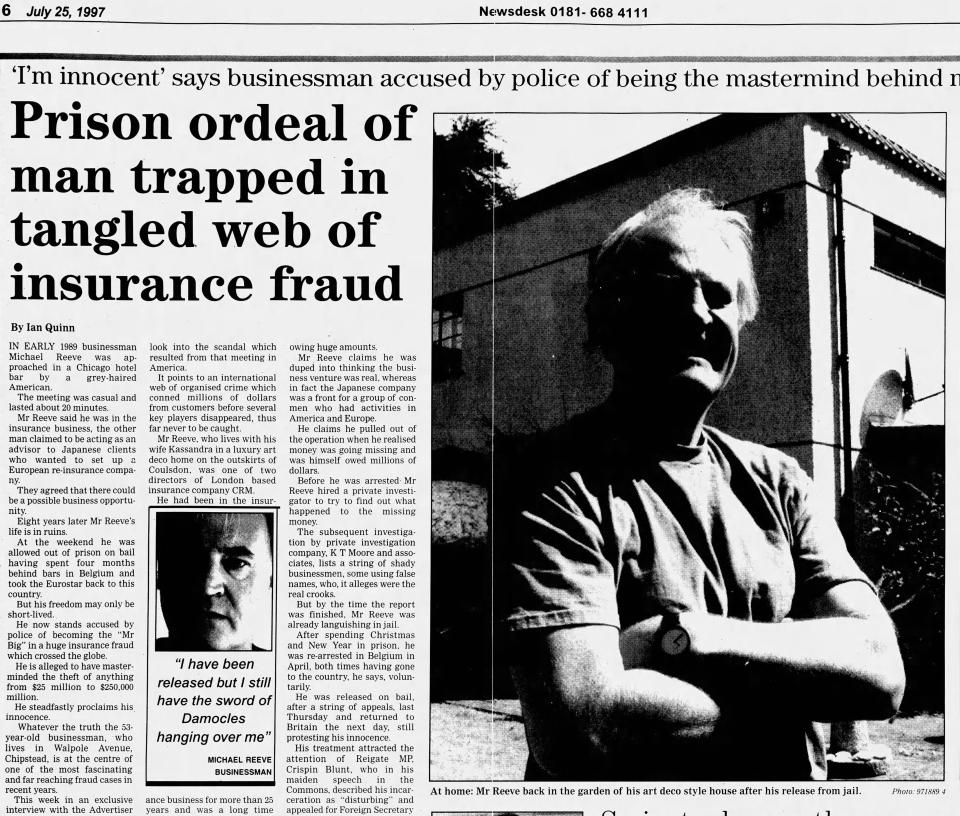

Reeve, who said he didn’t know his bosses were committing fraud, quit managing Dai Ichi Kyoto in February 1995 as the scandal unfolded. Belgian police arrested him in 1997 and he spent three months in jail. Belgian prosecutors later indicted him, along with seven other defendants.

Beekmeyer, meanwhile, rose to a prominent position at the company. When Reeve exited, according to prosecutors, company leaders gave Beekmeyer control of Dai Ichi Kyoto’s accounts for about six months.

Beekmeyer later told Insurance Security Services, a London industry newsletter, that he did not participate in the scheme. The newsletter’s author, Trevor Jones, wrote that Beekmeyer hired a law firm to investigate how the reinsurance company’s money had disappeared. Jones added that Dai Ichi Kyoto’s leaders were simply looking for someone to manage the office after Reeve’s departure.

“This was the aggressive but inexperienced Keith Beekmeyer, who made his own enquiries into the company and was fired (he says) for the results,” Jones wrote in November 1995.

Belgian prosecutors did not indict Beekmeyer, and he landed a job at another London firm, according to Insurance Security Services.

Just two years after Dai Ichi Kyoto’s bankruptcy, Beekmeyer emerged in London as an aspiring business titan. He and two partners founded a venture fund and bought companies around Europe, building a diverse conglomerate.

Beekmeyer’s rise surprised Reeve.

“So where did he get the money? Maybe he won the lottery," Reeve said. "He wouldn’t have gotten the money from what we paid him, to be sure. Maybe he had a rich grandfather who died or something. I have no idea.”

Tyler Jett is an investigative reporter for the Des Moines Register. Reach him at tjett@registermedia.com, 515-284-8215, or on Twitter at @LetsJett. He also accepts encrypted messages at tjett@proton.me.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Small-town Iowa insurers need help. But is their rescuer for real?