Help! I Brought My Wife and Her Ex Back Together. What Have I Done?

This is part of Help! Wanted, a special series from Slate advice. In the advising biz, there are certain eternal dilemmas that bedevil letter writers and columnists alike. This week, we’re taking them head-on.

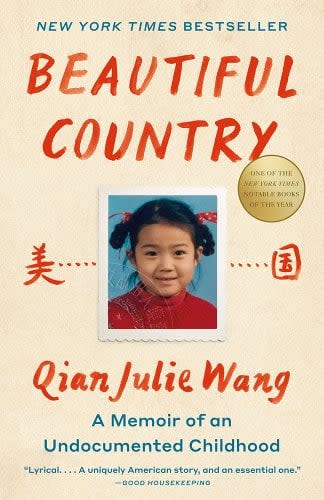

Today’s columnist is New York Times bestselling author Qian Julie Wang, whose book Beautiful Country: A Memoir of An Undocumented Childhood was a TODAY Show Read with Jenna pick and a best book of 2021 as chosen by the New York Times, President Obama, NPR, Newsweek, and more. Qian Julie is also managing partner of Gottlieb & Wang LLP, a law firm dedicated to advancing educational rights for marginalized populations.

We asked Qian Julie to weigh in on goblin-like jealousy, a competitive streak, and a big move:

Dear Prudence,

My wife used to have a very hostile relationship with her ex. It was so bad that I soon became the go-between when he came to pick up their two kids, dealing with any issues that needed to be resolved and trying to soothe both their hurt feelings over imagined (and sometimes quite real) slights. It was awful and I could see it was really hurting the kids, so a couple of years ago I (figuratively) knocked their heads together and insisted that they resolve their issues in therapy. It was a struggle at first and my marriage nearly collapsed because of it, but it has worked far better than I had ever expected. They are getting on like a house on fire, we have dinner together as a family, swap stories, and laugh. They and the kiddos are so much happier. I, on the other hand, am struggling. I find myself feeling intensely jealous whenever they’re together. I am so ashamed of it and, in the moment, I just go quiet or find a way to excuse myself, but it gnaws at me, particularly as we had some very bumpy months when I was trying to persuade them to get help. I know I should probably go to therapy but I cannot do that without my wife finding out about it and I do not want to disturb this new, precious balance we have achieved. For the moment, I have taken up a new sport as a kind of stress relief and am practicing meditation but perhaps you have another suggestion? This is not like me and I am hating these feelings.

—Little Green Goblin

Dear Goblin,

I am a deeply jealous person. I’m not exaggerating: I am jealous of every person who has ever looked at my husband or been in his company. He had a long dating history before me, and during our first few years together, I wished upon each and every one of his exes slow death by immolation. (I’m only sort of kidding.) This has little to do with him—he has a habit of bragging about me to everyone he meets within seconds. It has everything to do with me, and I suspect, my upbringing as an only child in poverty. Growing up, I frequently longed for the toys and food my classmates had and learned quickly to white-knuckle the few possessions I did have.

Frankly, you are a far better and less petty person than I am. I don’t think I would have had it in me to do what you did. Your wife is lucky to have you, and so are your stepchildren.

But it sounds like you are so used to being a good and bighearted person that you reject all of the little goblin parts of yourself that are inherent to being a real live human being. There are surely those who will fight me on this, but I posit that experiencing jealousy is a natural part of being alive—just as natural as feeling an urge to yell at the person who cuts us in line. But society is not great at allowing us to embrace our goblin parts. Rom-coms tell us that jealousy signals insecurity and weakness. But who, I ask, survives life without ever feeling insecure or weak?! We must be open and accepting; we must love our neighbors—and we are told this ad nauseam from the day we are born to the day we die. But what if our neighbors are assholes? What if they throw 4 a.m. ragers that keep the baby crying and the dog howling? How do we find love for them then?

It often feels as if the world demands us to be perfectly compassionate and kind. But that is not natural. In fact, I’d say that we cannot truly be kind or love others until we accept the goblin parts of ourselves. Because you know what also exists in those loud, asshole neighbors we must love? Goblin parts.

You say that you hate what you are feeling and feel ashamed. Brene Brown writes that shame needs three things to grow: “secrecy, silence and judgment.” I see all three reflected in your letter: You’re not able to share your experience of jealousy; you judge it and hate that it exists. I suggest starting with the judgment part: Please forgive yourself for being human.

You mention that you started a new sport. You can play tennis all you want and even make your way to competing in the U.S. Open, but so long as you continue to judge your feelings once you return to the locker room and beyond, they will not go away. I’m sure you’re beginning to learn in meditation that the more we reject our feelings, the more they fester. The problem is not jealousy itself. The problem is the shame you’re nursing over it.

I know this because I spent years unable to accept that I was, for lack of a better term, a jealous bitch. I was set free the day my husband called me out for being jealous and when I, instead of denying it, looked him in the eyes and accepted my title. Embracing my goblin parts liberated me. Embracing them also allowed me to see that while my feelings and thoughts were not necessarily kind, they did not define me. Feelings and thoughts are fleeting, and we are not always in control of them. In fact, like mischievous, rebellious children, the more we seek to control or repress them, the more they insist on defying us.

In yoga and meditation practice, we learn to sit with discomfort. Notice an itch on our body while we’re in lotus? Do not scratch it; observe it. The being that observes the itch cannot itself be itchy. The more we practice this, the smaller the itch becomes, until it fades entirely. So sit with your jealousy. Study its face, its green eyes, its textures, its many forms. The being that observes the jealousy cannot itself be jealous. The being that observes the jealousy cannot be defined by it. Jealousy does not detract from all the goodness that you are. It is fleeting, and merely a sign that you are human. To be human, as Rumi writes, is to be “a guest house.” So be a host with the most: “[t]he dark thought, the shame, the malice, meet them at the door laughing, and invite them in.”

The more you sit with your guests, the more you will see that they are not so bad, nor are they so permanent. They may even leave on their own. And you will, I hope, find the compassion you need for yourself. Then you might turn to the secrecy and silence you’ve maintained and wonder if you might be ready to open up to a therapist or your wife, who may very well welcome this new form of intimacy. Indeed, this jealousy might be the very thing that feeds the trust in your marriage—and in yourself. See you on the goblin grounds.

Dear Prudence,

I come from a very competitive family. My siblings and I were all in sports from very young ages. The competitiveness wasn’t just related to sports, though. My parents always had to be right, even at the expense of my feelings. Sometimes, they were downright bullies. I was always an easygoing person and was the highest achiever in my family, so I didn’t get the brunt of the negative effects, but I still got some. My issue is that I’ve recently noticed a random urge to be right. I’m no longer very competitive and am normally pretty laid back, but my need to be right comes up at the strangest times.

For example, I recently went on a trip with friends. We all live in different cities and flew to the vacation spot. One of my friends said she was so tired because she had to get up at 5 a.m. and my response was, “That’s nothing, I had to get up at 3 a.m.” There was absolutely no reason for me to say this and I can tell she got a little annoyed. The big issue is when this comes up when people are trying to give me advice. It mostly comes up when I’m trying to deal with a very difficult problem and talking to my friends about it. My friends will give me advice, often good, sometimes bad, but I almost always argue with them to try to prove my opinion is the best. Then, usually after a short period of time, I register the merit of their advice and use it to take some kind of action. I’m left feeling bad, though, that it took me so long to accept the advice. This has been a huge theme in my life where I seamlessly slip into some kind of competitive state in these types of arguments. A lot of times, I know it’s because I’m getting unsolicited advice, but sometimes it’s not and, either way, the advice is usually pretty good. I’ve surrounded myself with some very good people. I just hate that I get so argumentative when people are just trying to help. Do you have any advice?

—Argumentative Annie

Dear Argumentative,

First, an apology: You probably hoped to reach a calm and clearheaded Prudence but have found an angry litigator instead. I literally make a living proving that I am right. Your note of caution does not elude me: You get particularly argumentative when you receive advice, and that is the very thing you are seeking from me right now. So I should warn you that if you’d like to engage me in an argument, I am very much game, but I will have to bill you at my hourly rate.

Disclaimers out of the way, I relate 100 percent. A need to be right and to win was embedded in my bones—that is, until I married another angry litigator and we both had to figure out, for the first time in each of our lives, how to bite our tongues and pick our battles. (Mind you, this was only after we exhausted ourselves spending the first years of our relationship fighting over everything and nothing. Apologies to our neighbors.)

What I learned in my marriage is that when there’s an irrepressible need to compete and to win, there’s often an underlying belief or wound at play. You seem to be aware of this, having opened with a reference to your childhood. For me, it was growing up poor and largely emotionally neglected by my parents, who were too overwhelmed and underequipped to deal with the particular stressors of our life to acknowledge my feelings. Because they felt inadequate to deal with their own feelings, much less mine, they also bullied me: At the dinner table during my elementary school years and later, they would take turns mocking my looks, criticizing me about everything, and then when I fell into tears, declaring that I was just too spoiled and sensitive. It sounds like you might be able to relate to that. I cannot speak for you, but those experiences taught me that I could not rely on anyone. To be worthy, I had to be fully self-sufficient and the very best. And when people corrected me or gave me advice in my adulthood, it triggered me because it implied that I was not perfect, and therefore, not worthy. I think it’s telling that you seek out advice and then react: that suggests to me that your subconscious may be seeking to heal your own childhood wounds.

It’s similar but slightly different when the advice is unsolicited. When someone offers advice unprompted, it can often feel like a violation of our boundaries, a marker that who we are and what we’re asking for (often comfort, not solutions) is left unseen. It can also feel as if the person speaking is focused on working on their own issues instead of addressing ours. For those of us who had parents who did not always see us, or prioritized their needs over ours, this can feel deeply familiar and painful.

Regardless of whether the advice is solicited or unsolicited, I’ve been working on not being so reactive—although my stance remains that those who wander the world doling out unsolicited advice should just stay home, I don’t want the words of any person to have such a power over me that it triggers a knee-jerk reaction. And besides, arguing being my career, I don’t want anyone to have access to my expertise for free! But as I’m sure you know, it’s a long road—it takes many, many years of intentional practice to rewire our brain and nervous system after trauma, so as you embark on doing the same, I wish for you what I often don’t have for myself: patience and compassion.

What ultimately helped me tap into that patience and compassion was initially seeing not what was at play in me, but in my husband when he reacted with the determination to win. I saw the little boy he was, the dark hole of emotional neglect he grew up in, and recognized his intransigence as an early coping mechanism. Seeing that made it easier for me to see the little girl inside me and the hole she was still trying to climb out of today. In time, that image gave me the space to pause and step back, and begin to accept that responding with sharp barbs against others was never going to help that girl feel safe. What I needed to do instead was to turn to her and tell her that she was worthy just as she was, without a need to win or perform. She did not need anyone else to validate her, and she would never be abandoned again, because I would always be there to give her what she needs.

It is a difficult and long journey, to be sure, but one that has transformed my life and how I relate to others, but most of all, myself. My little girl and I send you and yours all our love as you embark on that same rewarding adventure.

Submit your questions anonymously here. (Questions may be edited for publication.) Join the live chat every Monday at noon (and submit your comments) here.

Dear Prudence,

Three years ago my husband, young kids, and I moved to a Midwestern city (not Chicago) for my husband’s job. In our previous city, I worked in a very specific field that has been my life’s passion since I was a teenager. I assumed, incorrectly, that I’d be able to find work in this area in my new city as well. Whether due to chance or the pandemic, or both, I haven’t. We now have the opportunity to move back to our old city, where I could have my old position back. The problem: My husband loves our new city. It’s much larger than the old city and has tons of activities for us and our kids, as well as a pretty good restaurant scene. We live in a charming leafy area 10 minutes from the city downtown with great public schools. It also has four seasons. The old city is much smaller with less to do, and it’s in the south so it’s mostly hot/warm. My husband thinks long term this is a better place for us and the kids to grow up. He also thinks it will continue to get better over time. However, I feel intense regret and sadness not being able to do this thing I’ve loved for so long. Do I do what’s better for the rest of my family, or insist on what’s better for me?

—Missing My Old Life

Dear Missing,

You’ve written to the right person. I’m 36 years old and I have moved 22 times. I’m currently sitting among cardboard boxes, packing for #23. Few of these moves were by choice, and I made many of them angrily and begrudgingly. But with the perspective of time, I feel fortunate to say that each and every move has carried me to greater growth and more fulfillment. My response to you will necessarily be colored by that experience, but I understand that this is not always the case for everyone, and only you can know best what is right for you.

My first move was at age 7, from north China to New York City. It was quite literally life-changing, and utterly terrifying. For the first months we were here, I bemoaned to my parents everything we left behind in China, and espoused an undying wish to return and act as if we had never left. It was then that my father told me a Chinese adage that has guided me for the rest of my life: bu zuo hui tou lu. It loosely translates to: Never turn around and walk down the same path. Do not retrace your steps. Or as we Americans say, you can’t go home again.

I didn’t believe him at first, but every time I’ve returned to one of my many former homes for a visit, I hear my father’s words. The rosy, sepia-toned memories lose their luster when revisited in the bright light of today. Each time it’s happened, I’ve had to accept that my memories of home in that particular place are locked in time—in a version of me that no longer exists, a version of a place that no longer exists. To assume that we can just return to a place, a job, or a community and recapture our lived memories exactly as we remember them elides the truth that we, as people, are ever-evolving—as are the communities we leave behind. If there’s one thing that remains static, it’s the fact that nothing and nobody stays the same.

The reality is that just as the past three years have changed you, it has also changed the job and the former home you remember fondly. You say that the pandemic may have affected things in the new city. Is there any chance it’s left your old city—and your old job—untouched? And is it possible that you might have since outgrown the job that had you feeling fulfilled three years ago?

From an early age, we are trained to see our choices through artificial limits: Do we want to eat our brussels sprouts before or after we finish our homework? And we are plugged into a sense of scarcity, particularly when we go through something as scarring as a global pandemic or something as frustrating as applying for jobs for three years to no avail. We better grab onto any offer that comes our way, it becomes easy to believe, because without it we will have nothing.

But I suspect that the choice here is not necessarily between what’s better for you and what’s better for the rest of your family; nor is it between never doing what you love and returning to your old job. I don’t know what field you are in, but is it at all possible to find a remote position in the same field that will allow you to stay in your new city? Is there any possibility of starting your own business in the field since, it seems, there is clearly a big gap for it in the new city with the larger market? Are your skills transferable such that you could work in a related, but slightly different field, so that you can do what you love but push your limits? Could it be (and I promise this is the last question!) that this might be the very challenge you need to further your growth as a professional and a person?

I have no guarantees. I would suggest that, rather than taking my word for it or making the decision based on memory or scarcity, you take some time to return to your old city, visit with your old job, and see and feel for yourself—the present you and the future you, not the past you—whether it all still fits. It is possible that it might still be the choice you want to make. But I’d caution you against making that choice with the expectation that the move will restore to you everything you remember your old life as being. If you do choose it, expect to build a brand new future with it. Do not choose it just because you are familiar with its scenery and are less scared of it. Whatever career choice you make should scare you a little because that’s how you know that it’s the one pushing you beyond your limits. So choose to return only if it feels like the old job is the one, among your panoply of exciting choices, that opens you to a wider horizon, to a more fulfilled and stronger you who will not just be an asset to your future colleagues, but also to the family you love so dearly.

My husband is very, very smart. He graduated from an Ivy League college, has published in academic journals in multiple fields, and achieved success in a competitive field while still in his 20s. That is all great, but what I like best about him is that he always wore his intelligence lightly. He prefers to ask questions than to expound, answers questions clearly and simply without being patronizing, and is always looking to find people smarter or more knowledgeable than him—he has no desire to be “the smartest guy in the room.” But that has changed in one specific context.