Henderson County’s longest-serving jail closed its doors as 1972 ended

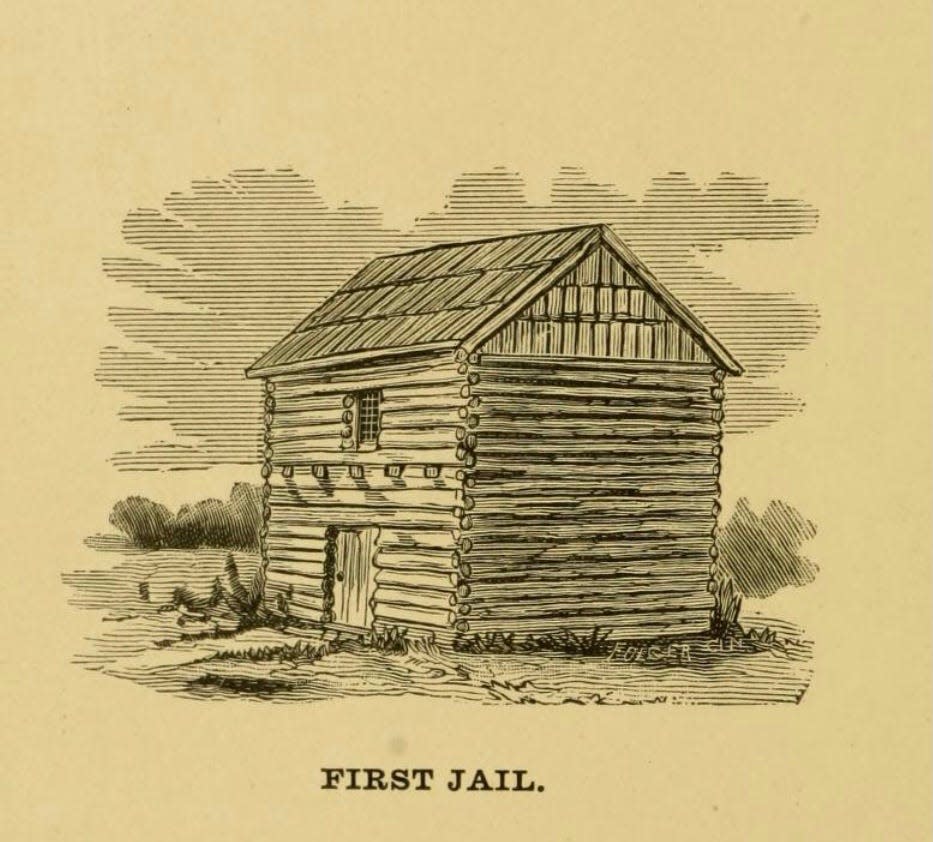

Henderson County’s first government building was a jail.

But it wasn’t the type of structure that word would usually call to mind. In fact, it more resembled a hog pen, according to E.L. Starling’s History of Henderson County. There was no way to heat the building.

Jonathan Anthony built the 12-foot-square, two-story building for $339 at the end of 1799 out of squared-off logs, with a single door and a small window in the upper story. A trap door allowed access to the second floor, which was the debtors’ prison for the financially insolvent. The bottom floor was the “dungeon” for more serious criminals.

It stood at First and Main streets on the corner of what is now the courthouse square. The first prisoners were Susanah and Sally Harpe and Betty Roberts, the wives of the notorious serial killers “Big” and “Little” Harpe.

The county’s second jail, built in 1807, was much like the first except it was 16-foot-square. It was so insecure that during its 13 years of usage what the county spent for guards was about five times what the structure had cost to build, according to Starling.

Local news:Former Gleaner, Courier & Press photojournalist honored as Kentucky Colonel

The third one finished in 1820 was a definite improvement – it cost $3,500. It was made of brick and measured 26 by 40 feet. “Outside of necessary repairs it was never much expense to the county and was never broken but twice in its 43 years.”

Henderson County’s first woman to hold elected office presided over that jail in 1850. According to County Court Order Book E, page 521, Frances Gobin, widow of the former jailer, was appointed to serve out her late husband’s term. Lazarus Powell and Thomas Towles Jr. signed her security bond. She remained the county’s only female jailer until 2017.

By 1860, though, the jail was showing its age and the county court began laying plans for a fourth jail. A committee was appointed but its report did not suit the court, so the matter was set aside until another committee could lay plans and hire a contractor.

The Henderson Reporter of Oct. 1, 1863, said, "The new jail is going rapidly up under the superintendence of the accomplished architect Mr. T.W. Carder. The walls are of heavy oak timber, two stories high, and a brick wall two brick in thickness will be built on the outside. The dungeons will be lined with a covering of sheet iron and taken altogether it will be one of the strongest prisons in the state."

Starling estimated that wall around the jail stood 15 to 20 feet high. That jail was completed by mid-1864, according to the Reporter. “The new county jail has at last been completed. The building was examined by the commissioners on Monday last. Everything having been finished to their satisfaction, the keys were handed over by Mr. T.W. Carder, the architect and contractor.”

I’ve seen it said that the jail built during the Civil War was the same building that stood in what is now the courthouse parking lot until early 1973. A close examination of the records, however, shows that’s only partly right.

“The present jailer’s residence is a part of this building,” Spalding Trafton wrote in The Gleaner of June 14, 1925. “After some years it became totally unfit for the purpose for which it was intended.”

The county’s fifth jail – the one many of you remember standing in what is now the county’s parking lot – was financed by $33,400 worth of bonds issued in 1871. The final payment was made to the contractor Nov. 30, 1872.

The Henderson News of Dec. 3, 1872, said “this strong, iron-cage is almost ready to receive occupants” who, no doubt, will “find it a difficult task to escape therefrom, save in a legal way.”

Local life:The night Franco Harris brought joy back to Evansville

Uh, not quite.

"This prison when completed was thought to be invulnerable," Starling wrote in 1887. "It was built upon the most approved plans of prison architecture, including strength and durability, yet it has been broken or cut through as often or perhaps oftener than any of its predecessors."

A mass escape in 1875 prompted the suicide of Jailer J. Elmus Denton, who had been severely critical of his predecessor about jailbreaks, according to the Evansville Journal of Dec. 20, 1875.

That building was the longest lasting of any of the county’s jails, although toward the end of its life it drew regular criticism from the grand jury about conditions there. On Sept. 29, 1970, the city fire inspector condemned the building and ordered it razed. On Oct. 22 of that year South Central Bell agreed to sell its former headquarters on Main Street for $50,000 so it could be converted into a jail.

The county’s sixth jail was unlike its predecessors in that it was not on the courthouse square; it was across Main Street from Central Park. The Gleaner of April 15, 1973, gave a synopsis of how it came about – which never would have happened without the leadership of County Judge John Stanley Hoffman. It required the voters passing a new tax to fund a $375,000 bond issue.

“In the November 1971 election local residents approved the bond issue by a vote of 3,889 to 1,476, more than 300 votes above the two-thirds majority of the voters. Four years earlier a similar proposal was defeated by a two-to-one margin.”

Construction began in February 1972 and the contract called for completion by Nov. 6. Problems obtaining steel delayed construction, but county officials declined to impose penalties, according to the Nov. 24 issue.

“It’s about as complicated and rough a job as you’ll run into,” said architect Davie Crawley. “We’re getting good workmanship. They just haven’t been able to complete the job in the allotted time.”

About 250 people viewed the renovated building at 11 S. Main St. when was dedicated Dec. 30, 1972; inmates were moved in Jan. 3, 1973. Hoffman noted it was one of only a few jails in the state that had a closed-circuit TV monitoring system and electrically operated doors throughout.

At the end of January Henderson Fiscal Court awarded a contract worth $3,628 to Marksberry Contracting Co. of Evansville to raze the former jail, which had stood for more than a century.

Demolition was scheduled to begin Feb. 15 although The Gleaner didn’t get around to publishing a photo of the demolition work until Feb. 18. On March 13 The Gleaner reported the work was done.

The county’s current jail accepted 91 inmates in mid-October of 1996. The jail/former telephone building on Main Street was razed in 1999 to make way for the Henderson County Judicial Center.

100 YEARS AGO

The interurban traction car that carried people to Evansville collided with a streetcar at Eighth and Elm streets, according to The Gleaner of Dec. 26, 1922.

The streetcar motorman, H.H. Lee, received cuts on his face from broken glass. He was treated at the hospital and went home.

75 YEARS AGO

The Rev. Charles E. Dietze was named pastor of First Christian Church, according to The Gleaner of Dec. 28, 1947.

For the previous year the Savannah, Georgia, native had been associate secretary/director of the Christian Churches of Kentucky. He also had served three years as pastor of the First Christian Church in Morehead.

Dietze, a religious and civic leader probably best known for his book “The Henderson Crusade” that detailed his fight against gambling and corruption here, died in 1996.

The Savannah, Georgia, native was pastor of First Christian Church here from 1948 to 1952 and returned here to retire in 1981. He authored two other books and was one of the founders of St. Anthony’s Hospice and Henderson’s Habitat for Humanity.

25 YEARS AGO

A dozen kids had a Christmas party at the Henderson County Detention Center and, even though they weren’t allowed to touch their incarcerated parents, the parents got to see them have fun, according to a story in the Evansville Press of Dec. 13, 1997.

A two-year-old placed ornaments on the tree while her father watched from behind bars.

“He’s going to state,” the child’s mother explained. “It’s probably the only chance she’s going to have to see him for a long time.”

Another pair of children, ages 8 and 11, were brought in by their aunt, who was caring for them while their mother was in jail.

“It’s hard for her to be away from her children especially at this time of year,” said the aunt. “And you know, you always want to be with your mom for Christmas.”

Capt. Finis Vincent Jr. said jail staff came up with the idea for the party while talking about decorating the conference room Christmas tree. After deciding which inmates would be eligible, he said, 10 were chosen at random.

The inmates were grateful. Some even hugged him and cried when they learned their children would participate.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Henderson County’s longest-serving jail closed its doors as 1972 ended