Henderson history: Factory full of kindling sparked biggest fire of 1923

The wildcat whistle that had been silent four years sprang to life with a screech to announce the rebirth of a factory that had been 1923’s biggest fire loss.

The Gleaner of Feb. 16 reported “several times the fire apparently was extinguished” at Anderson Box & Basket Co. “but slowly and steadily it crept along until, having reached the department where boxes were stored, it suddenly leaped high and the plant was doomed.”

A classified ad in the May 23 edition gives you an idea how combustible those boxes were. The company was selling scraps as kindling at $1 a load.

The fire was reported about 2 a.m. and both fire stations responded to the location at Vine and Alves streets. “A stiff wind carried burning brands over a wide area, setting fire to grass in yards, then to outbuildings and fences, but volunteers watched for each fresh outbreak.”

Fires broke out on the roofs of houses along Vine Street, but were quickly extinguished by firefighters and neighbors.

Anderson Box at that time was “one of the substantial manufacturing industries of the city. A number of men were given steady employment as the company operated on a full-time basis,” unlike the tobacco factories or the Heinz condiment factory.

Local life:Looking for some Mardi Gras food in the Evansville area? Here's the full list.

The fire hit at a bad time. The firm had been running at full capacity and was behind. Many orders for spring and summer were on file, so company officials were anxious to quickly rebuild. But a few words about the company’s beginnings before we get into that.

The destroyed factory had been built shortly after William O. Anderson and M.C. Deckert bought the property for $500 on Nov. 7, 1892. The low price indicates no building was on the site at that time. Bland D. Beverly bought Deckert’s interest Jan. 13, 1898.

A year later a group of businessmen headed by John H. Hodge incorporated the Anderson Box & Basket Co. and bought the property Jan. 6, 1899. An addition was added in 1908.

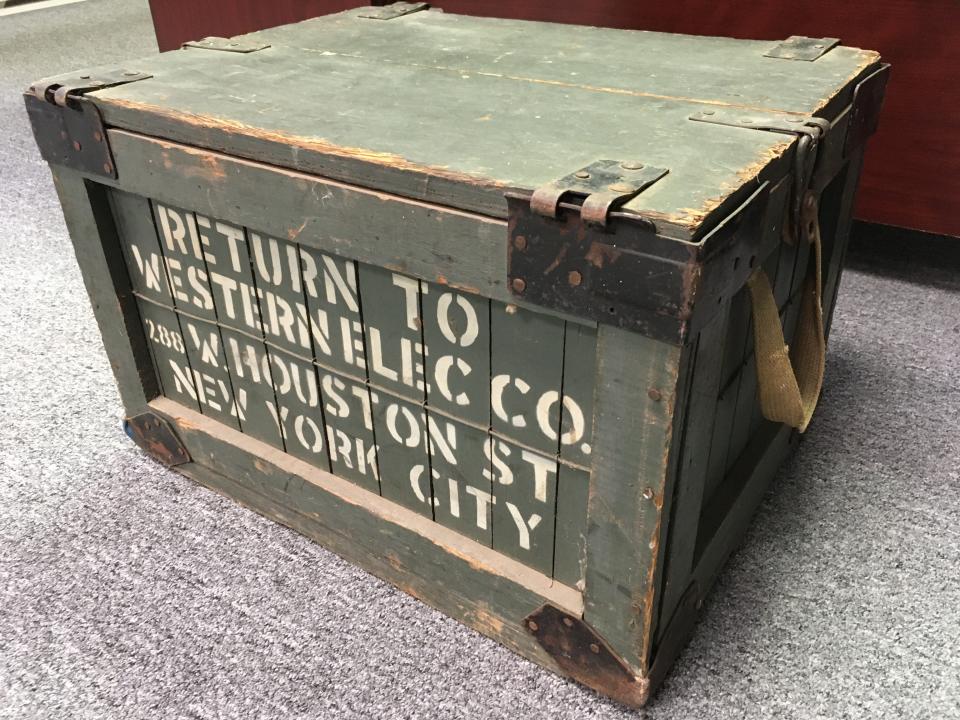

The company built “woven wood and wire shipping boxes, auto or wagon delivery boxes, floor truck boxes, showing trays etc.” according to a Gleaner article of July 24, 1927. The company did business over a wide area, according to a Nov. 9, 1919, article, which said it had “grown in financial strength and excellency of product to such an extent it is known throughout the United States and in Canada and Mexico as well as in other countries.”

The Gleaner of Feb. 18, 1923, noted “Evansville has made the firm an attractive offer to locate in that city.” But company officials were also talking to the Henderson City Commission, which offered free electricity and water service for five years, along with a waiver of property taxes.

Meanwhile, company officials were talking to Frank Delker about the old desk factory farther up the Belt Line at Mill Street. (East End factories were served by railroad tracks called the Belt Line, which until 1986 ran up the middle of Vine Street.)

The Gleaner of Feb. 20 reported a deal had been closed with Delker for the desk factory, a structure which had been built in 1906 and produced bedroom furniture for a year before becoming a desk factory for three additional years, according to a manuscript history by Jack Hudgions.

That story about the desk factory purchase also said the loss from the Feb. 16 fire had been $85,000 and was only partially covered by insurance. But The Gleaner’s 1923 fires wrap-up said the loss was $24,000, which still accounted for more than a third of the city’s total fire loss of $65,600 that year.

Gibney Oscar Letcher was manager and partial owner of the enterprise. He told The Gleaner in its Feb. 27 issue 40 to 50 men would be working when work resumed. “We were fortunate in retaining most of our orders we had on hand when our plant burned,” he said.

Local news:Company announces new 300-home subdivision for Henderson, Kentucky

All insurance policies had paid off and the desk factory building had been bought from Delker for $10,000, he said. The needed machinery had been ordered, and some of it would arrive that week, while former water works superintendent William Sieber had been hired to install it.

The March 9 Gleaner said “machinery is arriving every day and is being installed as soon as received…. The factory when completed will be larger and more commodious than the old factory recently destroyed by fire and the company will be enabled to operate on a larger scale; about twice as many men will be employed.”

While work was proceeding apace on the new factory, the owners decided to put the site of the burned factory to good use. The Gleaner of March 18 announced plans to erect a tobacco warehouse at the corner of Vine and Alves. (That building no longer exists.)

The Gleaner of April 22 announced the factory was reopening at 7 a.m. the next day with 35 to 40 men. Even better, beginning April 30 the firm had plans to work a night shift for several weeks so it could catch up on orders that had been on file when the old factory burned.

That story also woke up the wildcat that had been sleeping for four years. This is how it began:

“Citizens of Henderson were surprised Saturday afternoon when they heard the familiar sound of the ‘wildcat’ whistle which served at the cotton mill for more than 30 years. The whistle has been purchased by the Anderson Box & Basket Co. and installed at its plant acquired from Frank Delker.”

The whistle was to blow at 6:55 a.m., noon, 12:45 p.m. and 6 p.m. So it appears employees at the plant worked a 10-hour day.

That whistle apparently would take your head off.

A July 14, 1956, Gleaner interview with George Cooksey Jr. described the wildcat whistle, which was replaced by a 57-pound brass steamboat whistle when the cotton mill was undergoing renovations in 1919. "Cooksey said the boat whistle was put in because the wildcat whistle disturbed plant employees by its ear-rending scream.”

A deed filed June 6, 1949, says the firm had allowed its incorporation status to lapse, which resulted in a new company with the same name and directors to be formed. The old company then sold its assets to the new company. Every piece of machinery, and the date it had been bought, is listed in that deed; only a handful dated to 1923.

Local life:Valentine's Day: Couple has 70 years of marriage filled with baseball, dancing and family

The Anderson Box & Basket Co. made its final appearance in the city directory in 1950. The Gleaner of Oct. 16, 1962, reported the building at Mill Street, which at that time it was occupied by M. Livingston Wholesale Grocery, had been destroyed in a spectacular blaze.

75 YEARS AGO

Henderson Police Chief Leon Beckham advertised a warning in The Gleaner of Feb. 19, 1948, that Green Street would be vigorously patrolled because “a great deal of traffic … is moving too fast and is exceeding city speed limits.”

The speed limit in school zones was 15 mph. Motorists had to stay below 20 mph in business districts, while the speed limit in residential districts was 30 mph.

50 YEARS AGO

County Judge John S. Hoffman said a deal to acquire the 944 acres Gulf Oil Co. owned – the site of the ammonia plant during World War II – was close to resolution and that the property would be used to develop a riverport, according to The Gleaner of Feb. 21, 1973.

A riverport authority had been formed Jan. 6, 1970. Hoffman began talking to Gulf Oil in mid-1971.

“We could be in the riverport business almost from the day we buy it since docking facilities are already there,” Hoffman said.

The idea of a riverport for Henderson had first been raised by Mayor Hecht Lackey Oct. 25, 1954, but didn’t go anywhere at that time. Hoffman’s proposal also had trouble. Although the General Assembly had appropriated $400,000 for the port, six months later it appeared the idea was dead because of an unstable bond market and the lack of any major industrial prospects.

A 270-acre parcel was purchased for $900,000 in March 1977 from Gulf Chemical, inaugurating the Henderson County Riverport and industrial park. The county received a state grant the following month of $825,00 to pay for design and development of port facilities.

After a fitful start, the Henderson County Riverport opened for limited business early in 1980, but did not achieve a positive cash flow until 1997.

25 YEARS AGO

Louis Marshall Jones, better known to the world as Grand Ole Opry and Hee Haw star Grandpa Jones, died in Hermitage, Tennessee, according to The Gleaner of Feb. 20, 1998.

He was 84. He had been born Oct. 20, 1913, in Niagara, the youngest of 10 children. He adopted the Grandpa Jones persona at the age of 22.

He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1978. He was an original cast member of the TV show Hee Haw, which ran from 1968 to 1993.

In 1996 Smith Mills Cemetery Road was renamed Grandpa Jones Drive in his honor.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Henderson history: Factory full of kindling sparked biggest fire of 1923