Henderson history: Henderson power plant worker met horrific death in 1923

William Anderson Hulse was on his knees when death accidentally fell on him Feb. 10, 1923.

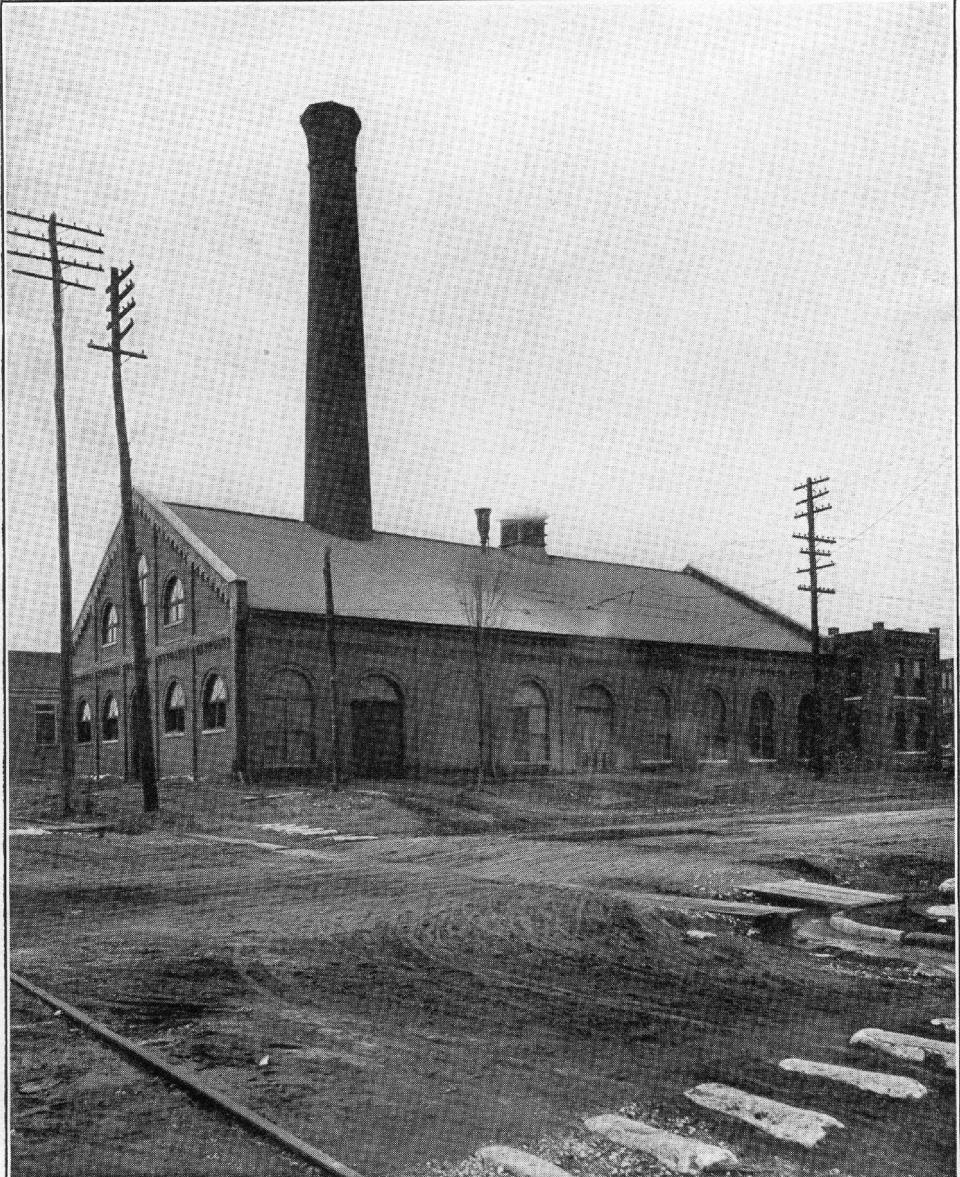

He had been working as a fireman at the city of Henderson’s original power plant about two years when that happened. Before that he had worked a similar job for the Henderson Route railroad.

A fireman, by the way, is not the same thing as a firefighter. Firefighters ride around on shiny red trucks putting out fires. Firemen, especially when coal was king, had responsibility for keeping fires burning.

I feel I first ought to first tell you a bit about the man before I provide the gruesome details of how Hulse died at the age of 32. There are inconsistencies, however.

The Gleaner of Feb. 11 said his name was W.H. Hultz. His death certificate, however, identifies him as William Anderson Hultz. His tombstone says William A. Hulse, but it appears to have been placed about the time his wife died in 1959. I suspect the family changed the spelling of the name sometime between 1923 and 1959.

I’m going to use Hulse because that appears to be the family preference. Also, it’s carved in stone.

He was born May 11, 1890, in Breckinridge County and grew up there. He does not appear in the 1920 Henderson County census, so he probably came here shortly thereafter. The Gleaner’s 1923 story about his death says he had been working at the power plant about two years.

He was 18 when he married a 17-year-old named Rosa on Dec. 23, 1908. (I’ve seen variations on her last name ranging from Fipps to Phipps to Phillips.) Between 1909 and 1921 they had six children: Ernest, Jesse, Louisa, Zora, Mildred, and Rosalie. His death certificate says the family lived at 439 Sixth St.

At his death, then, Rosa was a young mother with six children under the age of 12. And the Great Depression was right around the corner.

Fate could have taken several different turns for Hulse. He had been sick about three months and had returned to work only a week before the accident happened, according to The Gleaner‘s Feb. 11 story.

The original power plant generated electricity by burning coal, and someone had to clean the ashes out of the ash pit twice a day. That was Hulse’s job.

“A man goes down into the ash pit and rakes the ashes into an opening from which they are taken away by machinery,” the story explained. Hulse was on his knees, raking the ashes. He was about to be relieved by Ernest Winstead.

More:A Q&A with Brad Staton as he begins first year as mayor of Henderson, Kentucky

“With shovel in hand, Winstead started down the ladder and the shovel handle accidentally struck a lever that opened the door in the fire box and without warning the flames from the seething mass swept over (Hulse), who was on his knees in the position used for the task.

“His body was not touched by the blaze, but the intense heat and poisonous fumes completely filled the small space, which became a death trap from which the doomed man could not escape.”

He remained in that kneeling position until chief engineer Hugh Jenkins stepped onto the ladder and realized Hulse could not survive long from the fumes. Jenkins demonstrated remarkable bravery in attempting a rescue. He climbed down the ladder far enough so he could grab Hulse by the shoulders “and by a heroic effort” managed to pull him out far enough that he could grab Hulse by the arms and carry him to safety.

“Jenkins is chief engineer at the plant and has been connected with the station for 21 years. He said it was the most distressing accident at the plant during that time.”

Rudy-Rowland’s ambulance rushed Hulse to the Moseley Hospital and The Gleaner’s report says “within a short time his agony ended in death.”

That’s not quite true. I wish it were. His death certificate in one place says he survived a “few hours” but in another place it says he was under the doctor’s care for five hours until he died at 9 that night.

He was buried in Fernwood Cemetery Feb. 12. His wife Rosa was buried next to him after she died Aug. 1, 1959.

Hulse’s death was not the first for the city electric utility now known as Henderson Municipal Power & Light. But his death was the only one of them that did not involve 2,400 volts.

More:As Kentucky debates medical marijuana, McConnell's hemp push already lets people get high

What surprises me is the number of them: Six by my count. That’s more than either the Henderson Police Department or the Henderson Fire Department.

The electric utility's first fatality occurred June 23, 1913, and victim Arch Steffy was only 17 years old. Steffy was working on a pole at the corner of Ninth and Main streets with a crew that had his brother, Roy Steffy, as foreman.

Roy Steffy heard his brother scream and looked up to see him suspended from a wire, with smoke rising from his hand. "The elder brother mounted the pole and was severely shocked in attempting to take the screaming youth down. He realized that the only possible chance to save the boy\'s life was to kick him from the wire, and this he did. The boy fell to the ground, a distance of 18 or 20 feet."

Arch Steffy died there on the ground asking for his mother.

Edward Allen Brown, 30, died April 18, 1952, while working on Old Evansville Road near the city limits. When he started falling, he reflexively reached out and grabbed one phase of the 2,400-volt line. He fell against the other phase, which struck him in the face.

"Members of the crew watched in horror as Brown plunged to the ground from atop a pole after his climbing hooks slipped from the pole," The Gleaner reported.

Marion C. Woodard, 29, was killed Aug. 7, 1957, while working at the southeast corner of Fourth and Water streets. He and his brother (who electricity killed in 1981) were working off the same pole in opposite directions. William Elbert "Bo" Woodard “turned and saw his brother hanging limp in his safety belt, with his hand gripping the power line. He first tried to knock the hand loose. When he was unable to do so, he clipped the wire."

Marion Woodard died at the hospital minutes after his arrival there.

Sandwiched between the two brothers' deaths was a June 29, 1966, accident on Herron Avenue that killed J. Glenn Herron, 21, of Providence while he was stringing new line from a transformer.

Attempts at resuscitation were fruitless and Herron was dead on arrival at the hospital.

William Elbert "Bo" Woodard, 48, was Henderson Municipal Power & Light’s last work-related fatality. He was working on a 2,400-volt transformer on Graves Drive June 19, 1981, when he somehow came into contact with a live wire. He arrived at the hospital in a coma and never woke up.

His was probably a more peaceful death than the one Hulse suffered.

75 YEARS AGO

The Henderson County grand jury issued a report Jan. 23, 1948, in which it criticized local taverns for selling alcohol to minors and drunks. That prompted both County Judge Fred Vogel and T.C. Hollowell, the city’s commissioner of public safety, to publish warnings in The Gleaner of Feb. 6.

Hollowell’s warning was more sternly worded: “There have been many complaints of selling intoxicating liquors to minors and drunks by tavern operators in the city of Henderson. This will not be tolerated” and violators will be prosecuted. “No further warning will be given.”

I’m not sure how much heed was given to those warnings.

50 YEARS AGO

Henderson Fiscal Court unanimously endorsed participating in the federal food stamp program, according to The Gleaner of Feb. 6, 1973.

About 800 local families at that point regularly stood in line to received foodstuffs from the federal government’s commodity food program.

The Gleaner of March 21 reported the U.S. Department of Agriculture had approved the county’s participation in the food stamp program, which would probably take four to six months to implement.

An estimated 2,000 local families would be eligible to get food stamps.

“We will not phase out commodities until such time as all those eligible have been called in to register for food stamps,” County Judge John Stanley Hoffman said. “There will not be a period of time when we have no food program.”

25 YEARS AGO

City Manager Jeff Broughton implemented a policy banning the use of tobacco products in the Henderson Municipal Center and most other city-owned and operated buildings, according to The Gleaner of Feb. 6, 1998.

Broughton conceded he had made a procedural misstep in that such a ban probably should have been issued by the Henderson City Commission, which signed off on the manager’s action at its Feb. 10 meeting.

Henderson Fiscal Court had banned smoking in most areas of the courthouse March 11, 1997.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Henderson history: Henderson power plant worker met horrific death in 1923