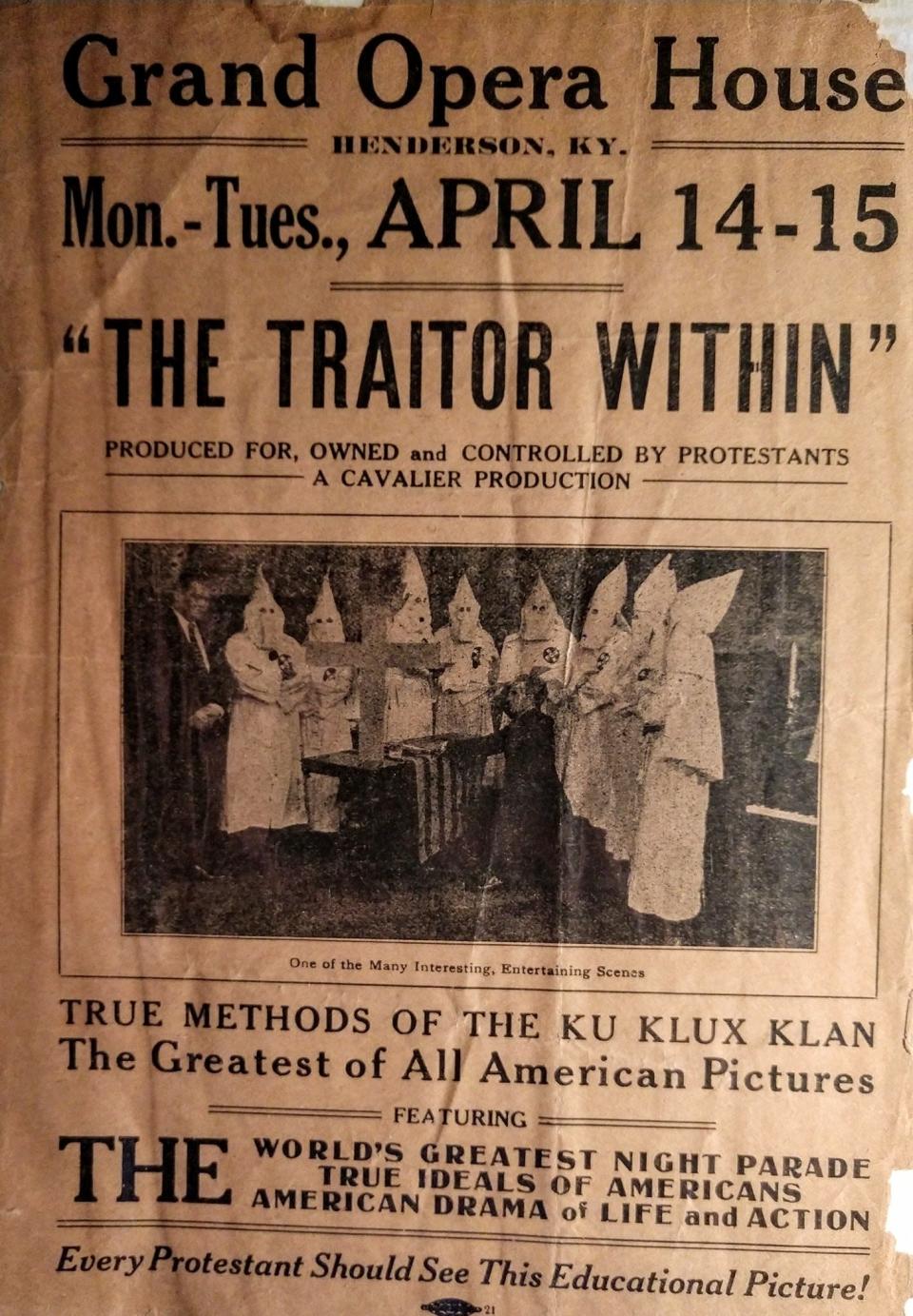

Henderson history: Ku Klux Klan’s crosses cast some dark shadows in May 1922

The Ku Klux Klan began infiltrating Henderson’s institutions about the same time it first brazenly paraded down Second Street.

The KKK has been a secretive organization since it began right after the Civil War, so in many respects it’s difficult to determine what it was up to. The Gleaner of the 1920s, for the most part, did not report its activities unless they were so blatant they could not be ignored. So, to some extent, I’m having to decipher the shadows cast by the light from those fiery crosses.

In December 1921 the Klan made donations to several worthy causes, which was the first time The Gleaner took notice of its local presence. The paper had been running stories about Klan activity elsewhere for several years.

On May 11, 1922, however, 183 fully robed Klansmen marched behind a flaming cross from Central Park to Union Station, with the Henderson Police Department and sheriff’s deputies maintaining crowd control. It’s not clear how many of the marchers were local men; a steamboat had brought a contingent from Evansville for the event.

Henderson news: 'Dearest Mom': Letters home from a Kentucky World War II soldier illuminate life at war

Crackdowns on gambling, dancing and showing movies on Sunday quickly followed. The new rules were strict, going so far as to prohibit prizes at card parties playing bridge.

“I am not going to be indicted for failure to do my duty,” Police Chief Ben McKinney told The Gleaner in the May 14 edition.

The May 31 edition reported Fire Chief Mike P. Abel was on the hot seat. The Henderson City Commission had sent him a letter of one sentence asking for his resignation by June 1. City officials were tight lipped about the cause.

Commissioner of Public Safety and Finance Frank S. Haag said only it was “because he was fighting the administration and was not loyal.”

Abel asked for a hearing before the city commission but was ignored. The Gleaner of June 3 reported he was still on the job.

“I want my friends to know that I am not guilty of any wrong-doing,” Abel said. “Any charge of disloyalty made against me is without foundation.”

The Gleaner’s last story about the dismissal of the fire chief appeared in the June 6 edition, which reported that the city commission had appointed Harry Stolzy as the new chief. He had been captain of the city’s main downtown fire station.

I can’t say with certainty Stolzy was a Klansman, but it seems probable because many Henderson County residents were at that time. In mid-June 1923 he had firefighters repair the basin of the Central Park fountain, which was filled with fire hoses. Trouble surfaced within a month, however, about a Black nursemaid who was overseeing a young girl splashing in the fountain. The nursemaid was not in the water; she was simply doing her job. Nevertheless, she was asked to leave by one of the firefighters. At that time Central Park was segregated, and the area where the fountain is located was on the side of the park reserved for whites.

The mother of the girl complained to the city commission, which told Stolzy he had no power to issue orders in the park. That prompted Stolzy to drain the fountain’s basin.

"I drained the pool because I don't believe in racial equality, and I don't care who knows my opinion in such matters," he told The Gleaner.

The Klan opposed minorities and immigrants, of course, but the Catholic church was also a major target. A letter to the editor from B.P. Manion that appeared Oct. 18, 1922, illustrates the pressure Catholics on the city payroll were feeling.

Manion had been fired from the water works after reporting J.D Gass had been sleeping while on duty –while Gass, who was a reputed Klan member, was promoted and got a big raise.

The city commissioners “claim they have no politics in their office,” Manion wrote. “I claim that there never was as much politics in any city administration as there is in the present one, and religious or rather Ku Klux politics at that.

Local news: How do Evansville area schools keep your kids safe? Finding out isn't easy.

“There have been seven Catholics fired to make room” for men who had worked to get the commissioners elected. “There are three Catholics left and in my opinion you will see them dropped one at a time when the present Ku Klux talk quiets down.”

Mayor Clay Hall was the head of the local Klan, Oscar Jennings told me before his death, and after researching Hall’s 1925 death for years I’m firmly convinced it was a political assassination. He was running for sheriff when a shotgun bought his campaign to a close a week before the election.

Charlie Davis and Judy Hayden put together a book in 1986 to commemorate the centennial of Holy Name of Jesus Catholic Church. In it they tell of “a wave of religious intolerance” in the mid-1920s that peaked with the mayor’s death and probably instigated the following incident.

Paul Moss told them, “the Ku Klux Klan called the rectory and threatened to burn Holy Name Church to the ground. “He (Moss) and two other non-Catholic friends, Alex Posey and Dace Howard, stood guard over Holy Name with shotguns for nearly a week. Luckily, the KKK didn’t make an appearance, and no one was harmed.”

Several other incidents in June 1922 demonstrated the Klan’s growing local presence.

The June 20 Gleaner carried a brief story about a Black man from Evansville named Wesley Cookie, who “was jumping fences in the neighborhood of Clay and Alves streets” when a police officer intervened and jailed him. Cookie’s explanation? He was trying to get away from the Klan.

“They’re after me. They hanged my brother.”

The June 6 edition reprinted a letter sent to Sheriff Otis A. Benton by the “exalted cyclops” of Evansville Klan No. 1, which was accompanied by a floral wreath “in the unusual form of The Fiery Summons.” Benton was recuperating in an Evansville hospital at the time.

The letter thanked him for his deputies’ work in helping keep the Klan parade of May 11 “true to the Klan principles” of law and order. It also expressed hope “that you some time in the future feel the inspiration to associate yourself with the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.”

The June 3 edition carried a story about a meeting of the Progressive Club, which contained this as its closing paragraph:

“Mr. D.C. Stephenson of Evansville covered a wide variety of subjects, placing a great deal of stress on immigration and the teaching of Americanism in the public schools. His address was very forceful and was well received.”

During the Klan’s heyday of the mid-1920s David Curtis Stephenson wielded ultimate political power in Indiana, largely because he was the Indiana Klan’s grand dragon. By 1925 the Klan had a quarter-million members in Indiana alone, which represented more than 30 percent of Indiana’s white men, according to an Aug. 30, 2012, article in Smithsonian Magazine.

The end of his reign came March 15, 1925, after Stephenson ravaged his aide Madge Oberholzer, who attempted suicide after suffering deep bite marks all over her body during her rape. “You must forget this; what is done is done,” he told her. “I am the law and the power.”

Oberholzer died and Stephenson was convicted of rape, kidnapping, conspiracy, and second-degree murder.

By 1928 Klan membership in Indiana had dropped to 4,000. By 1930 national membership fell to about 30,000 after a mid-1920s high of between 4 and 6 million.

75 YEARS AGO

Fishing near the Ohio River dams, which had been prohibited throughout World War II, was reopened, according to The Gleaner of May 25, 1947.

“Lockmasters have been instructed to open the reservations to visitors immediately,” Chief District Engineer B.B. Talley said. “Fireplaces, tables, benches, and rest rooms will be provided in the near future.”

Some areas remained closed because they were dangerous, Talley said, but they would be posted.

50 YEARS AGO

Henderson attorney David Thomason climbed a pole that had been erected on First Street near the courthouse in preparation for his fund-raising effort on behalf of the American Cancer Society, according to a photo in The Gleaner of May 27, 1972.

“Pledges are being taken – the amount per hour times the number of hours Thomason remains on the pole,” the caption reads.

His flagpole-sitting stint began June 3.

25 YEARS AGO

The state Alcoholic Beverage Control Board revoked the liquor licenses of Rumors nightclub at 3705 U.S. 41-Alternate, according to The Gleaner of May 30, 1997.

The licenses had been under suspension because of a gambling violation that occurred before Charles Shourds took control of the operation, which began featuring totally nude dancing in the fall of 1996.

The license revocation occurred because an inspector found a bucket of ice with beer in it behind the bar. The bartender maintained it was for the dancers. The ABC didn’t buy that excuse and cited the business for trafficking in alcoholic beverages during a period of suspension.

The nightclub continued offering nude dancing for several more years.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Henderson history: Ku Klux Klan’s crosses cast some dark shadows in May 1922