Henderson history: Labor troubles consistently dogged ammonia plant’s operation

Much of the output of the Ohio River Ordnance Works was dropped on Germany during World War II in the form of explosives. After the war, however, Henderson’s ammonia plant was still sending its product to the former foe.

Plant records are stored in the National Archives at Atlanta, which took the trouble to post on-line a synopsis of the boxes of documents it has on file.

“Labor relations were the biggest problem for the Ohio River Ordnance Works,” it says. “Labor unions wanted higher wages and were constantly negotiating. These negotiations often stopped production, which was damaging to the schedules of the ordnance works. The schedules were able to recover somewhat, but labor disruptions were on a constant cycle.”

More about that in a moment; first a little background.

Local life:Warm February has birds going about their business early. That's not a good thing.

The ammonia plant was one of 10 defense facilities the federal government authorized right before World War II began. The others were in Atlanta and Augusta, Georgia; Anniston, Gadsden and Birmingham, Alabama; Charleston, South Carolina; Chattanooga and Copperhill, Tennessee; and Flora, Mississippi.

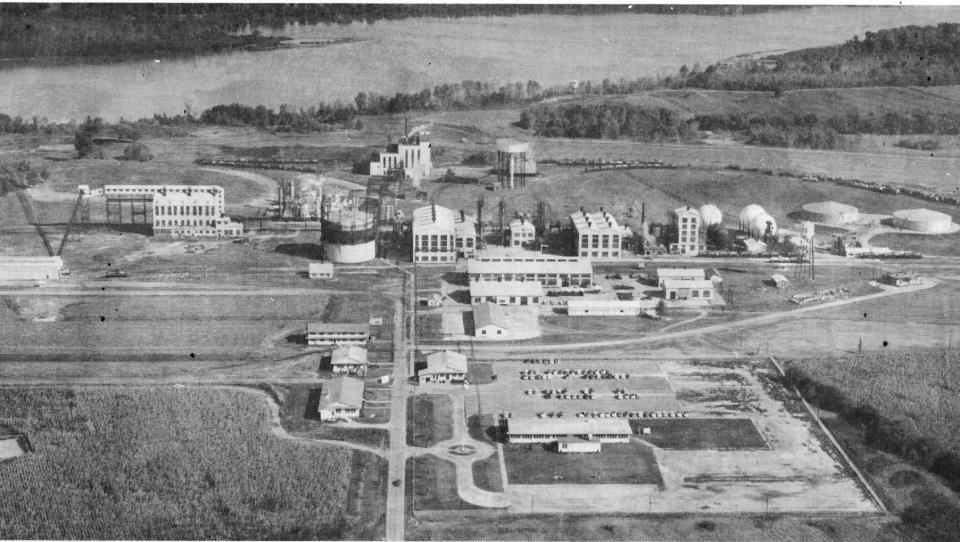

Construction of the local plant was announced Jan. 1, 1941, and on Feb. 15 a contract for construction of the plant was signed with Atmospheric Nitrogen Corp., a division of Allied Chemical, which operated the plant for a decade.

The contract for $15,484,195 (more than $315 million in today’s dollars) included $13.6 million for construction and $1.8 million for initial operations.

Ground wasn’t broken on the first two office buildings until April 29, although work on the main plant building didn’t begin until mid-1941. The facility was completed ahead of schedule in September 1942 and the first ammonia was shipped to ammunition producers on Oct. 16.

About 350 people worked at the plant, which was under the supervision of the U.S. Army, although only about 235 of them belonged to Local 291 of the International Chemical Workers Union as of March 7, 1948. That was the first inkling The Gleaner reported about a possible strike.

The longest closure the plant had endured back then began immediately after Japan surrendered, according to The Gleaner of March 19.

“Shortly after V-J Day the plant was shut down and 11 months later was reopened for conversion of ammonia into ammonia nitrate for use as a fertilizer for Germany.” (I’ve got an itch I can’t scratch in that I’ve been unable to dig up any further information about that program to help feed starving people in Europe.)

Henderson sports:Henderson County boys basketball peaking as it enters Second Region tournament

National labor leaders quickly swore their steadfast support of the war effort after the Pearl Harbor attack, but at the same time said they would not cripple their negotiating position by relinquishing the right of unions to strike.

Negotiations between ammonia plant managers and the workers had been ongoing since January 1948, with assistance from federal and state mediators. The original strike deadline was March 14, but it was extended to see whether the mediators could help.

At that time the starting wage at the plant was 80 cents an hour, which topped out at $1.30, according to the March 7 Gleaner. There was also a three-cent addition for workers on the swing shift and five cents for workers on the graveyard shift that began at midnight.

The plant operated on rotating shifts, meaning an individual worker would change shifts every two weeks. (I once worked in a factory organized like that and I can assure you it isn’t much fun.)

The union was asking for raises of 17.5 cents across the board, plus a five-cent differential for swing shift and 10 cents for graveyard.

The March 10 Gleaner reported workers had rejected the company’s offer during a meeting at the Central Union Labor Hall at First and Main streets. The company had offered raises of eight cents across the board, plus differentials of five cents for swing and seven cents for graveyard.

No progress was reported in the March 19 Gleaner; neither side had changed its stance.

“Mediation efforts collapsed Wednesday night and shortly afterward a crew of workmen started the process of closing down the huge ammonia producing plant,” which would affect about 350. “Last night all salary employees of (the plant) were on call at 12 o’clock to start the cooling off process, which is expected to take about 10 days The union had agreed to furnish a skeleton crew to carry out the shutdown.”

The pickets remained on duty while the plant was undergoing the shutdown process. The Gleaner of March 31 reported County Judge Fred G. Vogel had dismissed a charge of reckless driving against Tommy Hoffman, a foreman at the plant.

Henderson news:Henderson's longest-serving Black official talks about his career in public service

Harold J. Phalen, one of the men on the picket line, had sworn out a warrant against Hoffman, saying he had “operated an automobile toward him” on March 28. Defense attorney Landon Flournoy maintained the warrant was invalid because the incident did not take place on a public road and that Phalen had no right to be on the pavement approaching the gate. Vogel agreed.

That appeared to be the lone instance of physical confrontation.

The Gleaner of April 2 reported “last week all union men were pulled out of the plant after it had been put in a safe standby condition.” And the striking workers, in a meeting at the courthouse, authorized its scale committee to “take any steps toward settlement of the walkout it believed to be in the best interests of the workers.”

That vote came after the committee had met with J.J. O’Leary, “top official with the Atmospheric Nitrogen Corp.,” who had not only refused the 17.5-cent hourly demand, he had also refused to submit it to the Army’s chief of ordnance in Washington or to make a counter-offer.

The next day – April 3 – The Gleaner reported the 16-day strike had been settled after seven hours of negotiation, however.

Rocco Gonnella, the union local’s financial secretary, said the committee approved a one-year contract that provided for hourly raises of 9.5 cents across the board. But Gonnella said there was more. Employees who had worked at the plant a year were eligible for a week’s vacation, and that vacation would grow a day for every year of service.

The shift differentials, however, remained the same at three cents and five cents hourly for swing and graveyard shifts.

But changes were in the air. The National Archives’ brief history of the plant says, “The production of anhydrous ammonia was quite successful and maintained high levels of performance until late 1948 when coke used to make ammonia became extremely limited.”

Even bigger changes were to follow. Production of ammonia ceased April 20, 1950, and 15 days later, on May 4, Spencer Chemical Co. took control.

"We regret it is necessary for us to have to take the plant out of production at this time, however, we have to make the plant insurable, and a complete shutdown is necessary," Kenneth A. Spencer, president of Spencer Chemical Co., told The Gleaner shortly after the sale was announced.

100 YEARS AGO

The Vanderburgh County Commission agreed to spend $198,640 to build a concrete road from the Second Street ferry to Dogtown and designate it part of the Dixie Bee Highway, according to The Gleaner of March 9, 1923.

That nailed down the Indiana portion of the Dixie Bee; before that happened there had been efforts to route the highway past what is now Ellis Park. The Henderson City Commission had earlier designated which streets – beginning at the Second Street ferry -- the highway would follow through Henderson, according to The Gleaner of Feb. 9, 1923.

50 YEARS AGO

Three members of the Henderson Fire Department had part-time jobs as genuine cowboys, according to The Gleaner of March 8, 1973.

Larry Gibson, who later was to become the fire department’s crack arson investigator, had been working for three years tending a herd of about 1,500 cattle for the Reynolds Metals Co. Paul Walters had been on the job since May 1972. Eddie Wayne Wallace “pitches in occasionally to help out and for the excitement.”

25 YEARS AGO

The Tri-County area received a lot of water during the flood of 1997, but a year later it was getting a lot of money to compensate, according to The Gleaner of March 8, 1998.

About $5 million worth from the federal and state governments, to be exact.

Henderson County got the biggest share of the pie at approximately $4.3 million. Union County got a total of $449,104, while Webster County received $309,576.

Henderson County got about $2.6 million in the form of low-interest loans from the Small Business Administration. Union County got $262,800 in SBA loans, while Webster County received $89,100.

Other programs that provided support were the National Flood Insurance Program, temporary housing grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Kentucky Disaster and Emergency Services grants, as well as state and federal assistance to local governments for repairs to roads and other public improvements.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Henderson history: Labor woes dogged ammonia plant’s operation