Henderson history: Last local Confederate veterans were dying in the 1920s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I used to brag about my Confederate heritage because I thought it represented my taste for independence. Historical research and deeper reflection have changed my mind.

Many people – including aging Confederates from the 1920s – maintain the South was fighting for state's rights.

Well, yeah, but if you read the original documents, where southern states withdrew from the Union, you'll see that the right they were most concerned about was their ability to own fellow human beings.

But it got worse – if that's possible – once I began doing genealogy. The ugly truth is that my great-great-grandfather was probably a war criminal. On April 18, 1864, his cavalry unit fought in the Battle of Poison Springs in Arkansas, which was infamous for the slaughter and mutilation of Black prisoners of war from the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry.

Local life: Here are 8 things to do this weekend in the Evansville area

A consolation is that my great-great-grandfather on my mother's side died in Missouri fighting to preserve the Union. So, like our great country's history, my family history is a mixture of good and bad.

The thin gray line of local Confederate veterans was growing thinner as the 1920s progressed, and Spalding Trafton romanticized Capt. Paul Jones Marrs in The Gleaner after he died June 4, 1923. That's not surprising, considering Trafton’s father served with Marrs on the staff of Gen. Adam R. "Stovepipe" Johnson, Henderson County's most famous Confederate. More about Marrs in a moment.

I suspect other Confederate stories in The Gleaner during the first half of 1923 were also written by Trafton because they shine the same golden haze around the "Lost Cause."

The first story appeared March 6 about a man known as George W. Walton, who was reputed to be the oldest man in the county. He would have been 100 if he had lasted another month.

But that wasn't his only claim to fame. He was also a veteran of the Mexican War, which is probably why Confederate veteran Virginius Hutchen – in writing in the Aug. 10, 1909, Henderson Twice-A-Week Journal about Kentucky's Orphan Brigade -- called him a "very useful man." I suspect he learned the basics of artillery during the Mexican War, because he spent most of the Civil War in artillery units.

He also spent several months in a hospital after a Union soldier ran a bayonet through Walton's shoulder.

It wasn't until March 18, 1923, that Henderson residents learned George W. Walton wasn't his real name. His friend, Sen. Henry Dixon, had mailed copies of The Gleaner's story about his death to his sole surviving niece in Maryland, which prompted a story to be published in the March 13 issue of The Sun in Frederick, Maryland. That story was then mailed back to Dixon, who shared it in the March 18 Gleaner.

As it turned out, the tough old veteran's real name was Ezra Mantz. He assumed a new identity when he ran off from his apprenticeship as a hatmaker to fight in the Mexican War.

The stories about James W. Burns ran April 20 and May 6. The first was about his recent return from a Confederate reunion in New Orleans. The second was about him reminiscing on the porch of his house on Letcher Street.

Burns was born Feb. 16, 1842, in Livingston County and died April 15, 1926. He and 117 other men formed the 3rd Kentucky Co. C in July 1863 at Clarksville, Tennessee. Only six of them survived the war. As of 1923 only two of the original soldiers remained.

The war was mostly hardship, he said, noting he fought in 10 battles and nearly 50 skirmishes. "He declared he had walked forty and fifty miles a day without anything to eat, and that he lived almost without eating."

One time he nearly lost his life trying to scavenge sugar from hogsheads along a riverbank. He kept a sharp eye out downriver but wasn't expecting company from upstream. He saw the gunboat just in time to scurry up the bank and hug the dirt. The grapeshot "seemed to cut a swath through the underbrush," he said.

Local life: Love the birds in your yard? Here are 4 things to avoid so you can keep them healthy

"He laughed heartily at what he regarded as a joke on himself, but at the time it happened he did not have time to see the funny part of it."

Two stories were also written about Capt. Paul Jones Marrs, the first on June 5, the day after he died, which was brief, and the second June 24, which was not. He was born Feb. 28, 1838, in Posey County but moved to Henderson at age 6 after his father died. He began work in a local dry goods store while in his early teens but mostly worked in drug stores before the war.

He sold his business interests when the war began and enlisted as a private under Stovepipe Johnson, who was a colonel at that point. Before long he was a captain and quartermaster of a regiment, which raided West Franklin, Indiana, and captured guns, ammunition and horses from the home guards there.

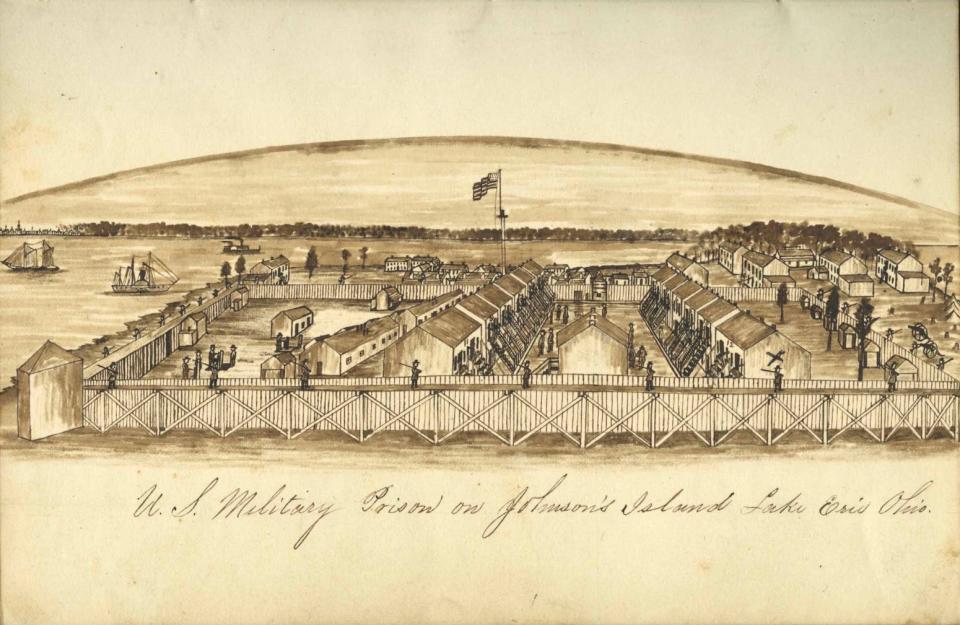

A Union force out of Henderson responded to the raid and captured Marrs and others. They were at first imprisoned in the Henderson courthouse before being moved to Evansville, then to Indianapolis and finally to the Federal prison on Johnson's Island near Sandusky, Ohio.

Marrs and others were exchanged in mid-1863 for prisoners the Confederates were holding.

That resulted in Marrs retrieving the horse he had rode to war on, according to Marrs' contribution to Johnson’s book, "Partisan Rangers." Archibald Dixon bought the horse at a government auction and when Marrs was released he sent word that Marrs could get the horse at his convenience.

Marrs did just that and rode it throughout the rest of the war. When the war was over, he returned the horse to Dixon, and it ended its days pulling a buggy.

The war also left Marrs with a little quirk: He always had a buckeye in his pocket. He told Trafton that his company once stopped under a buckeye tree, and everyone picked up a buckeye nut for luck. Four men did not – despite the warnings of the others.

"Later on, we had a considerable skirmish, and three of the men who had no buckeyes were killed, and the other one wounded. Therefore, I carry a buckeye."

Since I'm writing about the Civil War, I should include some information about a current exhibit at the Henderson County Public Library and associated events in June.

The display in the Genealogy and Local History Department focuses on the career of the Rev. Paul Horace Kennedy, who was 15 in 1863 when he escaped slavery to join the Union Army.

He walked from Elizabethtown to Louisville to join the 109th Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops as a musician. He got himself an education after the war – a doctorate, no less – and began his life as a minister.

He arrived in Henderson Jan. 1, 1881, to pastor First Missionary Baptist Church, which with the library is co-sponsoring the events. He found the congregation "worshipping in the basement of an unfinished building," according to Maralea Arnett’s "Annals and Scandals" book.

From then until he died in 1921 very little of importance in the Black community happened without him at the forefront.

Kennedy's cleaned up military tombstone will be rededicated at 11 a.m. June 17 at Fernwood Cemetery. A reception, which some of his descendants from Detroit are expected to attend, will take place the same day at 2 p.m. at the library's exhibit.

75 YEARS AGO

Worsham Post 40 of the American Legion was asking relatives or friends of veterans who had died since May 1947 to notify the legion so a cross could be prepared to install in Central Park on Memorial Day, according to The Gleaner of May 4, 1948.

In 1947 the display in the park featured 565 crosses.

50 YEARS AGO

The Gleaner of May 2, 1973, announced the Henderson City-County Human Rights Commission was being reorganized after a hiatus of two years.

The local Human Rights Commission began as the Mayor's Bi-Racial Committee, which was originally formed June 22, 1961. That was a mere 12 days after two dozen people had attempted to integrate Ken's Korner restaurant at Center and Green streets.

The mayor's committee morphed into the Human Rights Commission by late 1962, but it apparently fizzled out. The Gleaner of March 2, 1967, reported it was being revived.

25 YEARS AGO

The Kentucky Department of Parks made it official, according to The Gleaner of May 1, 1998. There would be no more swimming at the 28-acre lake in Audubon State Park because of a muddy lake bottom, vandalism, and a growing problem with parents of young children leaving them there unattended.

The park attempted to limit swimming to residents of the park cabins during the 1997 swimming season, but that didn’t quite conform to legal niceties and caused controversy at the time.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Henderson history: Last local Confederate veterans were dying in the 1920s