Henry Wallace killings exposed flaws in CMPD homicide investigations, sparked changes

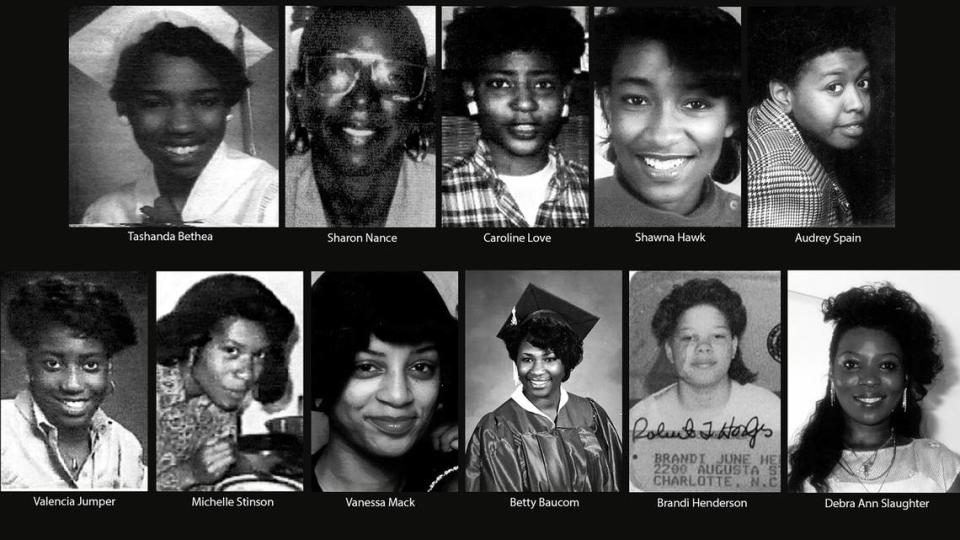

Charlotte serial killer Henry Louis Wallace killed 10 women in east and west Charlotte over a 22-month period before he was identified and captured in 1994.

The question remains: How?

Thirty years later, former detectives involved in the investigation and families of the victims still debate why Wallace was able to kill for as long as he did.

Mecklenburg Sheriff Garry McFadden, a former Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police homicide investigator assigned to the Wallace case, said race played a role — that in the early 1990s CMPD put less emphasis on solving crimes in African-American neighborhoods.

Dee Sumpter, whose daughter was murdered by Wallace in 1993, says police would have been more aggressive and possibly saved lives had the killings occurred in more affluent parts of the city.

Darrell Price, another former detective who helped track down Wallace disputes the notion that race was a factor, as do other CMPD officials. But Price acknowledged that the case revealed multiple weaknesses in how police handled homicide investigations at the time, leading to widespread reforms that remain in place today.

McFadden, Sumpter and Price made their comments to the Observer in 2018. Contacted recently, Sumpter and Price said they stand by their earlier statements. McFadden declined further comment.

A Killer's Long Shadow

30 years ago, Henry Louis Wallace cast a murderous shadow across Charlotte, raping and strangling 10 women before his arrest. Wallace's killings broke up families, stole daughters and sisters from their loved ones and left seven children without their mothers.

As a serial killer moved like a shadow across Charlotte, one woman made a promise

In 1994, Charlotte police searched for a murderer. They caught a serial killer instead

Serial killer strangled his mother. Now, he says, it’s Henry Wallace’s turn to die

Henry Wallace killings exposed flaws in CMPD homicide investigations, sparked changes

11 victims in two states: A timeline of Henry Wallace’s killings in Charlotte and SC

Did race play a ‘major part’?

Wallace was convicted in 1997 of raping and killing nine women. All were African American. All were friends or acquaintances of the killer. All were strangled — a rarity in Charlotte at the time.

Wallace told police he murdered a 10th Charlotte woman in May 1992, but that case was never taken to trial. He also confessed to the 1990 rape and strangulation of a Barnwell, S.C., teenager, which occurred before he moved to Charlotte.

Despite so many killings and the rarity of strangulations, police became aware they were chasing a serial killer only a few days before Wallace’s arrest. Even then, detectives did not know the full scope of Wallace’s killing spree until he jotted down his victims’ names during his confession.

McFadden said he was among fewer than a dozen investigators — and the only African American — assigned to the case. He alleged that the race of the victims and the fact that many of their murders occurred in minority or blue-collar neighborhoods influenced how the investigation unfolded.

“I think (race) played a major part, if you want to be honest about it,” he said in 2018. “We say that we investigate cases the same, but I would say we did not. We did not use the manpower. We did not use the time.”

Critics have long questioned the police department’s handling of the case, claiming that the deaths of the young women never became a priority because the victims were Black.

McFadden, however, appears to be the first officer involved in the investigations to raise the allegation publicly. In the early 1990s, he said, serious crimes in predominantly white or more affluent areas were far more likely to become CMPD priorities.

“We called them ‘ZIP code cases.’ You do things a little differently,” he told the Observer. “If it happened over on the other side of town, we brought out everything. If it happened over here, no, we brought out fewer bells and whistles.”

‘It just never stopped’

Price, who helped track down Wallace and interrogated him after his March 1994 arrest, said the investigation took as long as it did because the detective unit was critically understaffed and failed to uncover or connect some clues. Wallace also proved to be one of the shrewdest killers Charlotte police had ever encountered, he said.

While Price said he was familiar with the term “ZIP code cases,” he contends that race and geography never influenced how police worked the cases.

Statistics from 1992-94 prepared by CMPD show that the department handled almost four times as many cases with African-American victims (237) as whites (60). The clearance rate for Black victims was slightly higher — 84.8 percent to 84 percent — which was far above the national average for all cases, CMPD says. The Wallace killings, some unsolved for almost two years, are included in the “cleared” category, CMPD says.

“If we didn’t take those cases as seriously, I don’t think our clearance rate would have been 84.8 percent,” Price said. “Race had nothing to do with it. You wanted to solve that crime.”

Price’s comments mirror what acting Police Chief Jack Boger said in defense of his department a few days after Wallace’s arrest.

“Nobody wishes more than we do that we had found out after Day 1 — but we didn’t,” Boger told the Observer in 1994. “If someone could show me evidence of a pattern of discrimination, I’d certainly do something to fix that. I don’t believe it would have been any different if the victims had been 10 middle-class, white women.”

McFadden and Price agreed that the investigation leading to Wallace was impeded by other factors — from too few detectives handling a record number of homicides to flaws in CMPD procedures that resulted in too little internal communication about cases and too little interaction with the victims’ families.

In response to public pressure, CMPD doubled the size of its detective staff soon after Wallace’s arrest and also created a cold-case unit. At the time of the Wallace killings, though, detectives frequently faced numerous homicides a week.

According to CMPD records, Shawna Hawk, Sumpter’s daughter, was one of five homicides over a five-day period in February 1993; Audrey Spain, another of Wallace’s victims, was among six killings over a week that June.

Said Price: “It just never stopped.”

McFadden said police at that time did not have “the luxury” of discussing the investigation with families or delving into the victims’ backgrounds.

Had they, “We may have seen where Henry crossed most of those paths,” he said. “Could we have prevented these cases if we had looked at this a little closer? Possibly.”

Retired homicide detective Sgt. Tom Athey, who said he was McFadden’s direct supervisor for the decade following Wallace’s arrest, challenges the notion that racial bias influenced CMPD’s investigations. He told the Observer in 2018 that McFadden never raised any concerns with him about the Wallace cases or any that followed.

That McFadden is raising the allegation of bias decades later “is absolute fantasy land,” Athey said. “It’s really insulting to everybody who ever worked in that department.”

‘Opening the wound’

Then and now, the families of the victims offer a variety of viewpoints.

“When we look at the whole picture, we feel the Charlotte police department shouldn’t be badgered, but they should be praised for what they have done,” Alphonso Slaughter said in March 1994 after Wallace’s arrest, which occurred the day after police found the body of his daughter Debra.

By comparison, Hawk’s strangulation went unsolved for more than a year. Thirty years later, Sumpter, her mother, says the Wallace detectives wore “purposeful blinders” that kept them from interacting with families or spotting the similarities between the killings that should have led to an earlier arrest.

“We were shunned,” she said. “They would not talk to us. The police did not know there was even an ‘us’ back then.”

Sumpter, who credits CMPD for making significant reforms in response to the Wallace case, recalled how city officials told her at the time that homicide detectives “were overworked and understaffed.” She still finds the response lacking.

“When you say that to someone with fresh wounds from losing a loved one, that doesn’t wash ... That’s like taking a stick and opening the wound and then pouring in the salt,” said Sumpter, who co-founded the support group, Mothers of Murdered Offspring, in the wake of her daughter’s death.

“If Shawna had been murdered in Piper Glen, then or now, top priority would have been given. Every day the homicide detectives walked into a war room. You see the same information on the board. And no one is connecting the dots? No one? These are all African-American women. Blue collar. And nothing is being said or done.”

“For two years this man was literally allowed to run rampant in this city,” she said. “The things that Henry Wallace did to my daughter and the others defies what makes us human.”

Price, who most recently headed the police department’s ‘cold case’ unit, disagreed. He said the city has several longstanding homicides from affluent areas that remain unsolved.

“I understand her (Sumpter’s) anger and frustration. She lost a child, and nothing will ever change that,” Price said. “But I just don’t really have a response other than to say I do not believe that if Shawna Hawk had been murdered in Piper Glen, it would have changed anything.”

‘Wake-up call’

At the time of McFadden’s comments on race, the Observer attempted to contact many of the detectives who worked the Wallace case. Some had retired. Several had rejoined CMPD on a part-time basis. Other than McFadden, they either declined comment or did not respond to multiple emails. Boger also did not return a 2018 phone call seeking comment.

CMPD made Price available after receiving a summary of McFadden’s statements from the Observer.

During 1992-94, when the Wallace killings occurred, Charlotte-Mecklenburg averaged more than 105 killings a year. In 1993, the county set an all-time high of 132, according to state crime records. That was about three times the number from five years before.

Unlike CMPD’s murder investigations today, McFadden and Price say, detectives in the Wallace years rarely discussed cases among themselves, making it less likely that similarities between killings would be spotted.

With so many cases, the homicide detectives “barely had time to say ‘hey’ passing each other in the hallway,” Price said. “That’s obviously one of the things that changed after these murders — communication.”

By 1994, similarities in the Wallace killings had begun to surface but were not initially picked up on. Boger acknowledged at the time that the investigation did little research into the victims’ backgrounds.

Most of the crime scenes showed no signs of a struggle around the doorway, indicating that the victims trusted the killer enough to let him into their homes.

But the detectives never learned — until Wallace told them — that Wallace worked with several of the women at a Taco Bell on Sharon Amity Road; that one of his victims was the roommate of his then-girlfriend, while another, Brandi Henderson, lived with one of his best friends.

There were also strong similarities in the killer’s method. Charlotte-Mecklenburg may have been hit with record numbers of killings during 1992-94, but fewer than 5 percent were strangulations.

Wallace’s fourth victim, Audrey Spain, and his seventh, Vanessa Mack, were killed in almost identical fashion — with double ligatures, says Price, who was lead detective on the Spain case.

But Price said he first saw Mack’s name when Wallace wrote it down on his list of victims. As it was, the strangulations of the killer’s final four targets during a three-week period in 1994 helped break open the case.

Asked why detectives did not spot the string of strangulations earlier, Price said, “I don’t know the answer to that.”

“It was as if each case was in an individual can, and now I know you can’t do that,” he said. “We had never experienced a serial killer. We knew they were out there, but we didn’t think we would come across one.”

Today, Price said, the similarities of some of the women’s deaths would have been spotted earlier by CMPD’s crime-analysis unit or would have surfaced during the regular meetings homicide detectives now hold to discuss cases, Price says. Neither of those existed in the early 1990s.

Police also likely would have homed in earlier on Wallace with modern DNA testing and expansive computerized background checks, he said. Investigators also spend more time interviewing victims’ families.

Chris Dozier joined CMPD in March 1994, the same month of Wallace’s arrest. Now a retired captain, Dozier once headed the department’s violent crime division.

Given CMPD’s improved technology, training and communication, the department is far better equipped to recognize and stop a serial killer, he said, adding that the race of the victims is irrelevant.

“It doesn’t matter to me if that girl lives on Fairwood Avenue in west Charlotte or on Sharon Road in south Charlotte. It’s the same grief and suffering that the families go through,” Dozier said in 2018. “We treat every homicide as a high priority.”

Anne Tompkins, one of the two Mecklenburg assistant district attorneys who helped put Wallace on death row, says the detectives were “siloed” during the 1990s, one of the failings CMPD addressed after the Wallace case.

“I think this made them more aware that they had to pay attention to each and every victim,” said Tompkins, a former U.S. Attorney. “It was a wake-up call for police, and they woke up.”

Said McFadden: “A wake-up call is the easy way to put it. It was an earthquake, and we got the message ... We started listening to people, and we never wanted to be in that position again.”

The case still haunts him, he said.

“People lost their daughters,” McFadden says. “They entrusted us with their safety. We like to think, ‘You move to Charlotte, we’ll take care of you.’ Did we take care of them? No, we did not.”

Gavin Off contributed.