'Her journey is uncharted': 9-year-old Delaware girl with rare disease is beating the odds

Cassie DeChene is truly one of one.

Her mother, Elizabeth DeChene, and father, James DeChene, will be the first to tell you that the 9-year-old is one of the happiest and most outgoing people they know.

Family, friends and strangers are all drawn to Cassie's friendliness. Her personality is just as unique as the genetic disease she overcomes every day.

At 2 years old, Cassie was diagnosed with a mutation in her CHD4 gene. Around 100 people worldwide have CHD4-related neurodevelopmental disorders, and Cassie is the only one known with her specific gene change.

So far, that hasn't stopped her.

When the DeChenes sat down as a family to watch "Toy Story 2" earlier this summer, James and Elizabeth DeChene realized just how much their bubbly daughter has progressed since birth.

It was the picture-perfect moment for the family, watching their daughter go from being unable to make it through five minutes of a movie to watching every minute of the 1-hour-and-35-minute runtime.

The past nine years have been an up-and-down rollercoaster. Doctor appointments, physical and occupational therapy, and pre-planning for every trip away from their Newark, Delaware, home have always been on the minds of James and Elizabeth DeChene.

Among the lows and the highs, Cassie has found a home at the Newark Charter School and in the Delaware community. And it's driven James and Elizabeth DeChene to share their story and inspire other families with children who have rare diseases.

"Every step of her journey is uncharted," James DeChene said.

Diagnosing Cassie

When Cassie was born in December 2013, nothing stood out to Elizabeth and James DeChene as being abnormal. The birth was a successful C-section, and they had a healthy baby on their hands.

Elizabeth DeChene is a genetics counselor at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, so when she noticed a few things off by the time Cassie was a couple of months old, she brought it up to Cassie's pediatrician.

Cassie wasn't lifting her head as well as typical for her age, and her strength lagged a bit behind what her parents saw with her 13-year-old brother, Grayden.

Around 5 months old, Cassie started receiving occupational and physical therapy after her care team confirmed developmental delays.

But for the next couple of years, the DeChenes held off on having Cassie tested further for specific diseases. Her doctors assured them that when additional testing for Cassie would be beneficial, they would let them know.

“We chose to delay because I was worried if we get a diagnosis very early, it could impact our ability to bond as a family,” Elizabeth DeChene said.

When Cassie was 2, a doctor eventually recommended that the family proceed with genetic testing. Results came back in early 2017.

James DeChene still remembers the phone call to this day. It was a shocking, life-changing moment.

Testing revealed that Cassie had a change in her CHD4 gene, a condition that neither parent carried. Cassie's change in the gene is predicted to be "loss of function," which means she likely has only one working copy, producing approximately 50% of what she needs from the CHD4 gene.

No loss of function case had been recorded at the time of her birth to the DeChene family's knowledge − other CHD4 variants are considered "gain of function" and come with serious medical needs.

Cassie's diagnosis isn't complete − it's always ongoing − but there are no glaring medical drawbacks right now. Her change, which renders her neurodivergent, has most impacted her speech and attention. She was diagnosed with speech disorder apraxia at an early age.

Impulsiveness and distractions are two of the biggest challenges she faces to this day. The family is thankful for what she can do, though, especially given the unknown odds they encounter as Cassie grows.

They were told years ago that there was a legitimate possibility that their daughter may never walk or talk, since her disorder and its effects on her physical and mental capabilities were so unknown.

"Our hearts were broken," Elizabeth DeChene said. "Your whole life is shifted ... because you have all these hopes for your kid."

Now, Cassie is not just walking or talking, but running 5Ks at Newark Charter's Girls on the Run program and talking up a storm to her family and friends.

“She’s just a happy-go-lucky kid," her father said. "She loves everybody; she’s never met a stranger.”

The DeChenes have been fueled to share their story and lobby for a collective voice in the state government.

This June, Elizabeth and James DeChene were the honored family speakers at a gala supporting the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia's Rare Diagnosis Center. It's an event held by Cool Cars for Kids, a nonprofit organization supporting rare genetic disease research that the family has supported since it started.

But the advocating hasn't stopped there, as the family has supported a new Delaware bill passed during the current legislative session that will be integral to improving the lives of those with rare diseases.

Rare Disease Advisory Council

Families such as the DeChenes raising children with rare diseases often struggle to find resources, teachers and therapists.

Senate Bill 55 is a step toward organizing those resources more effectively. The bill establishes the Rare Disease Advisory Council in Delaware, which will be made up of professionals and individuals with rare diseases. The council will receive staffing from the University of Delaware's Institute for Public Administration.

The bill has passed both the House and the Senate and is expected to be signed by Gov. John Carney in July.

Lt. Gov. Bethany Hall-Long is a proponent of the council and said it will help improve efficiency in assisting everyone involved.

“Not only is it a benefit for families and recipients, but it is also extremely effective for health care providers and health care systems,” Hall-Long said.

The 14-person council will provide updates to the governor every three years on its work and function within the lieutenant governor's office.

James and Elizabeth DeChene spoke at Legislative Hall earlier this session when the bill was in its beginning stages. They have high hopes that the bill can streamline some of the processes of finding caretakers, physicians, schools and more.

One of the most difficult things for families in Delaware, Elizabeth DeChene said, is processing paperwork and information in person.

Two years ago, a Delaware bill removed restrictions on telemedicine in the state. This was a big step, after a previous report card from the National Organization for Rare Disorders noted Delaware as one of 14 states to "fail" in telehealth services − a mark that Delaware now passes, per NORD's methodology.

Telehealth services include the ability for patients and providers to "exchange health information without being in the same room," according to NORD.

And as of last year, 24 states had established Rare Disease Advisory Councils. Now, Delaware joins that growing list.

Hurdles still remain though for families trying their best to support a child with a rare disease. The DeChenes say that applying separately for every service that Cassie needs is a handful, as well as reapplying by paper instead of electronically.

They hope these hurdles can be eased by the new council, so Delawareans caring for children with rare diseases have fewer hoops to jump through.

Persevering through a period of struggle

Jumping through hoops is tiring enough, but families caretaking for children with special needs often face an entire set of struggles personally. The DeChene family is no different.

After raising Grayden, some of the changes they had to make during Cassie's first years were challenging. Routine is important for Cassie, so going on road trips or public events or even Grayden's lacrosse games have not always been easy decisions.

Cassie is always exploring, walking outside and talking to new people − which means her parents have to keep a keen eye on where she is at all times. It impacts how much time they can spend with one another and Grayden.

“You’re seeing the life that you thought your kid was gonna have being lived out in your friends – which is great," James DeChene said. "But it also changed our approach: Are we going to go to a party and bring Cassie along? Because she’ll be overwhelmed.”

But with time and patience from her parents, significant strides have been made. Cassie's neurological and educational developments have been tenfold, as her attention span has improved along with her sense of others' personal space.

More: US News & World Report reveals children's hospital rankings amid legal scrutiny

Earlier this summer, the family went to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, for Grayden's lacrosse tournament. It was Cassie's first time staying in a hotel, and it meant the world to her parents to see her able to handle the change in routine.

At times, it's hard to believe how far their daughter has come. But it's even more exciting that Cassie's ceiling − "if she has one," as her father said − hasn't been reached yet.

'So many random acts of kindness'

James and Elizabeth DeChene have learned that the people around them have been the key to success.

Cassie started off at Christina Early Education Center, which her parents say was an amazing fit. They then moved her to Newark Charter to ensure she would be in a classroom with other kids.

Cassie's parents said that teacher Sue Davis "figured Cassie out" when she began at Newark Charter. The techniques used by teachers like Davis have pushed Cassie to make strides in school.

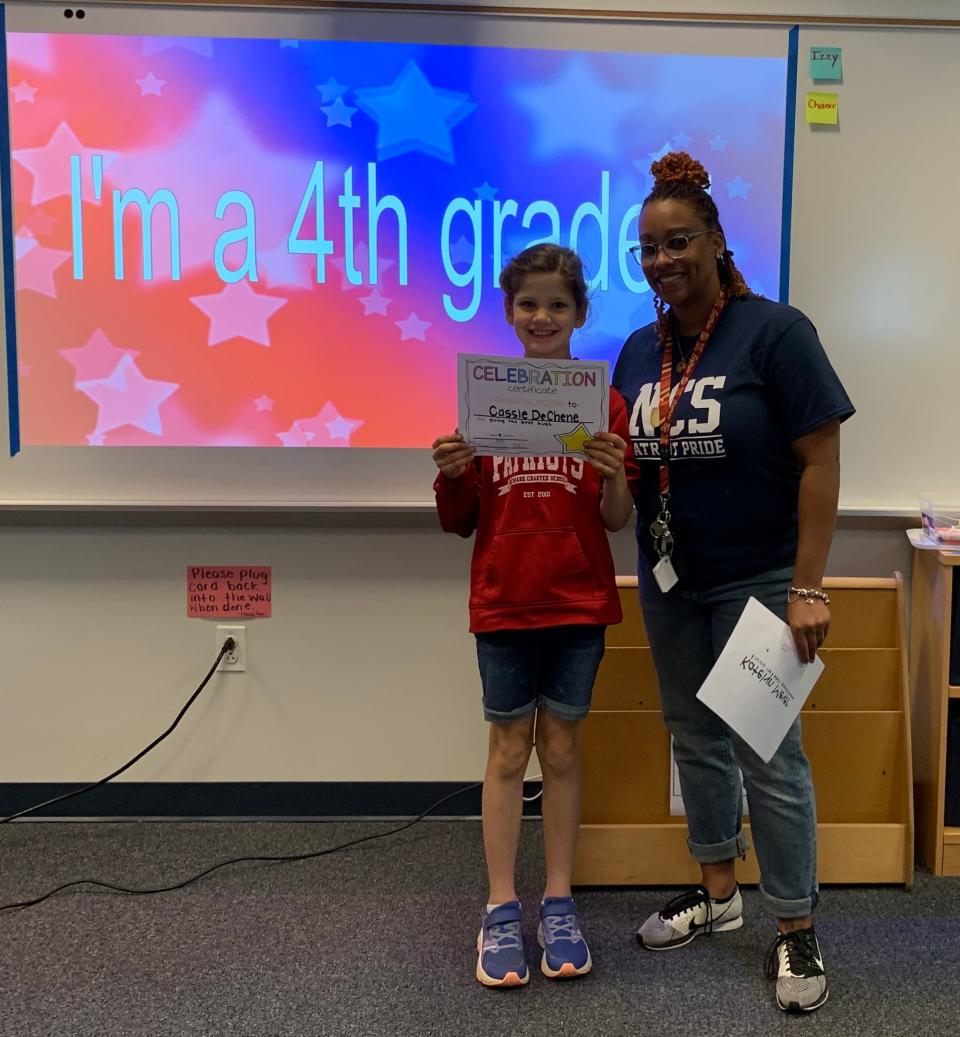

Chalisa McCray is Cassie's current teacher at the Newark Charter School. Last school year was McCray's first time with Cassie in her classroom, but it didn't take her long to notice what's so special about the "loving" 9-year-old with an infectious smile.

One moment stood out so much that it made Cassie's father emotional, McCray said.

When he walked into the classroom on a normal day, Cassie turned around, said hello to her dad and went right back to the task at hand. James DeChene said moments like those bring him to tears of joy.

“I never thought it would get to a point where she could regulate her behavior to have that kind of disruption and then refocus,” he said.

It's more proof that people like McCray who work face to face with the children are the backbone of the rare disease community, the DeChenes said.

“I don’t teach to her disability; I teach to her ability and build on that," McCray said. "We push kids beyond what their quote-unquote expectation is.”

And it's not just teachers and therapists who the DeChene family is thankful for − it's the everyday person. Take the man selling popcorn outside of Grayden's lacrosse tournament earlier this month, Elizabeth DeChene said.

The man didn't get upset when he saw Cassie reach her hand into the popcorn machine unpermitted. Instead, he gave Cassie a free bag and connected with her parents since he also had a child with special needs.

“There have been so many random acts of kindness from people,” James DeChene said.

For subscribers: Nurses endured COVID's darkest days. Now, they spoke to us about lessons learned

Biggest piece of advice for other families?

The creation of the Rare Disease Advisory Council will be a valuable asset for Delaware families. But just because living with a rare disease or caring for someone with a rare disease gets easier doesn't mean it will ever be easy at all.

Fighting for what's best for your child can be daunting, especially when dealing with health insurance and coverage of services, according to the DeChenes.

At times, Elizabeth DeChene says she's found herself holding back from asking for help, not wanting to be a "burden" on others. But looking back at the past nine years, that's one of the things she advises fellow parents of children with rare diseases not to do.

“My one piece of advice would be to trust your instincts," she said. "The few times we have not advocated as actively for Cassie and we’ve kind of tried to hold back and wait, we always wished we had said something."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Delaware girl with rare genetic disease inspiring others with progress