From her Lexington backyard, poet Ada Limón’s latest book finds light amid despair

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Poet Ada Limón spends much of her work and leisure time on the screened-in porch behind her house in north Lexington, which looks out on the broad expanse of backyard that seems somehow familiar to anyone who has read her work.

Behind us is the “maroon crabapple,” the “tawny yellow mulberry leaves that are always goldfinches tumbling.” There hanging over the fence is the giant hackberry tree the sparrows flew into in the poem “It’s the Season I Often Mistake.”

That poem appears in Limón’s new book, “The Hurting Kind,” along with more trees and horses and flowers — and allusions and metaphors and visions — that begin in this backyard and then go far beyond.

Nature is “definitely what keeps me at ease and at peace, when I’m most untethered and in the depth of despair, and how can you not be?” Limón said. “We’ve reached 1 million dead from COVID? And with Ukraine and climate crisis and the recent racial killings in Buffalo. When I’m starting to get like I can’t even, I don’t want to be part of humanity, I can watch the birds, look at the size of the worm ... there’ s sense of continuation, there is a little bit of an ease that it brings that to me.”

This is her refuge from the national stage that is her professional home. “The Hurting Kind” is Limón’s sixth poetry collection and the first book since “The Carrying” in 2018 which won the National Book Critics Circle Award. The book before that, “Bright Dead Things,” was a finalist for the National Book Award. She’s won a Guggenheim among many other awards and speaks to hundreds of thousands in hosting American Public Media’s weekday poetry podcast The Slowdown. This new book has garnered interviews and articles in the New York Times, NPR and The Atlantic. On the day we spoke, she had just returned from readings in California, which is her first real emergence in the wake of COVID.

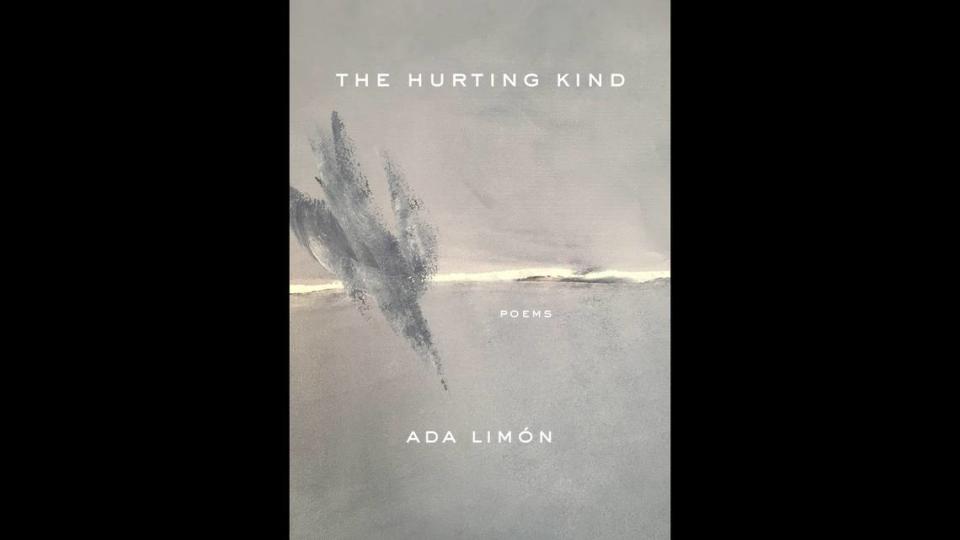

“It does feel like there’s a real longing to be in community and you can feel the isolation, so in that way it feels really refreshing — people in the book line are saying I need to tell you about the things happening to me,” she said. The book’s title and its arresting abstract cover of a black bird hurtling toward a gray sea assume it’s about two years of isolation, and it is. “But people are surprised that the book is so tender, that the book is full of good stories about family, even though it’s acknowledging all this grief and sadness and climate change and crisis, and the pandemic of course. But I think that even in its heaviness, they’re really surprisingly emotional that there’s some light in it.”

Light like the poem “Joint Custody” about her California childhood.

“Why did I never see it for what it was:

abundance? Two families, two different

kitchen tables, two sets of rules, two

creeks, two highways, two stepparents

with their fish tanks or eight-tracks or

cigarette smoke or expertise in recipes or

reading skills. I cannot reverse it, the record

scratched and stopping to that original

chaotic track. But let me say, I was taken

back and forth on Sundays and it was not easy

but I was loved in each place. And so I have

two brains now. Two entirely different brains.

The one that always misses where I’m not,

and the one that is so relieved to finally be home.”

At one of her readings, a woman in her 30s thanked her for the poem because she’d always been embarrassed to have four parents turn up at school events. “It was so beautiful,” Limón said. “Society tells me I’m supposed to be embarrassed about it so I’m embarrassed about it, but it’s so silly right? What is it society’s stories do for us? I think the book is for me questioning those stories. What are the stories that have been put on us that we don’t have any use for anymore?”

One of the stories that she has no more use for is about Kentucky. She moved here 11 years ago to be with her now-husband, Lucas Marquardt, a racing journalist who now owns a video marketing business for race horses called ThoroStride.

“I can’t tell you how fiercely defensive I have become about Kentucky,” she said with a laugh. “When you go somewhere and people say ugh you live in Kentucky, and I want to say, you don’t know! I am hundred percent a champion of Kentucky — how many people have a backward view of it? I take a deep pleasure in writing about Kentucky’s views and its people.”

And its horses. In “Bright Dead Things,” she wrote the poem “How To Triumph Like a Girl,” which won the 2015 Pushcart Prize.

“I like the lady horses best,

how they make it all look easy,

like running 40 miles per hour

is as fun as taking a nap, or grass.

I like their lady horse swagger,

after winning. Ears up, girls, ears up!

But mainly, let’s be honest, I like

that they’re ladies. As if this big

dangerous animal is also a part of me,

that somewhere inside the delicate

skin of my body, there pumps

an 8-pound female horse heart,

giant with power, heavy with blood.

Don’t you want to believe it?

Don’t you want to lift my shirt and see

the huge beating genius machine

that thinks, no, it knows,

it’s going to come in first.”

In the new book in the poem “Foaling Season,” she writes:

“of foals, mare and foal, mare and foal,

all over the soft grass there are twos ....

Everywhere doubles

of horses still leaning on each other, still nuzzling

and curious with each new image.”

Still later in the poem, she drops in “I will never be a mother,” a reference to a now accepted struggle with infertility that was made more difficult and intense while living in a place literally devoted to the business of breeding.

“It’s very weird — when I was going through fertility treatments, I was like this feels like too strong of a metaphor, it feels too obvious,” she said breaking into her frequent burble of laughter. “It feels like a cosmic joke. Now I think being child free is what I was meant to be, but it’s so interesting to think I’ll never have that moment, especially if you’re watching 20 mares and foals... It’s like this almost relentless image that comes up.”

Limón’s conversational style is part of her universal appeal, said Jeremy Paden, a poet and professor at Transylvania University, when I asked about her popularity. “She can be funny, and it not be mean-spirited, as humor and irony are more often directed toward herself or toward highlighting societal problems and ignorance rather than used as ad hominems. She does not shy away from hard and painful topics, but explores them with tenderness. While using her experiences as the source for the stories she tells, her poems are not self-indulgent vignettes that say, ‘Hey, this happened to me.’ Instead, they hone in on the emotions at play and in order to explore universal experiences. She also has a great ear for language, a control of the line, and strong, vivid imagery.”

Limón spent years in New York working non-stop at magazines like Martha Stewart Living, and she counts part of her success as the ability to live the life of an artist, but a balanced one, with plenty of time for friends and gardening and birdwatching with her constant companion, a queenly pug named Lily Bean. She teaches in visiting professor gigs at places like Columbia and Stanford, jobs that allow her a much-needed freedom to read and write and simply be.

She writes in her journal every day but takes time between crafting poems.

“It’s a little bit like how can we listen and receive the world if we’re always talking to the world? she said. “I feel like I need to listen and to just be and then eventually poems will come when I’m sort of ready to make space for them.”