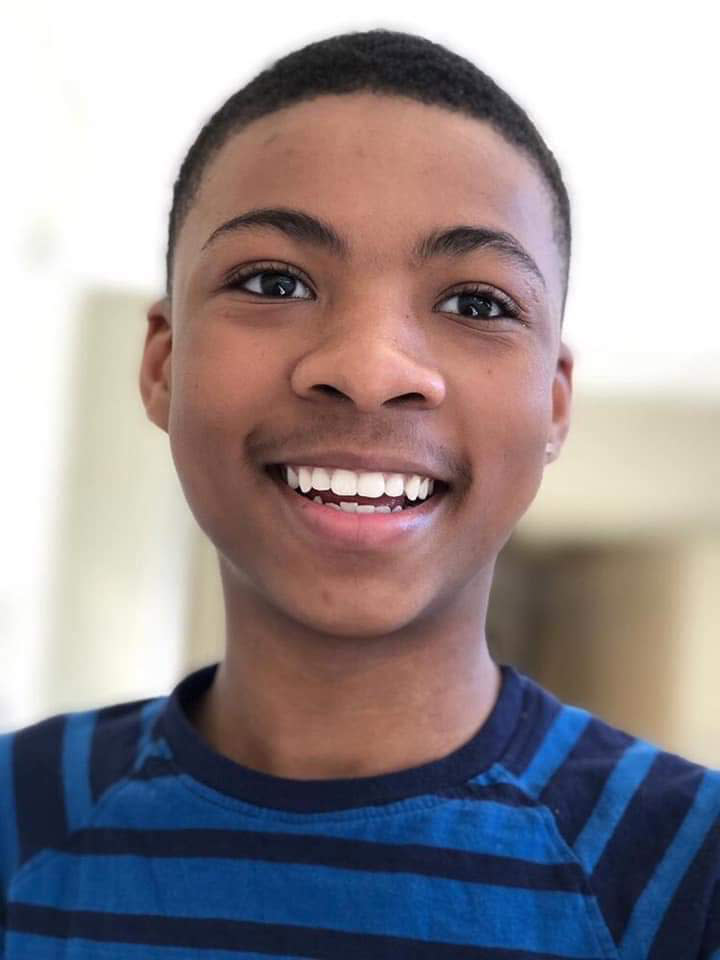

After her only son died by suicide, a mother wants other gay Black students to thrive

Four years after a gay Black teenager in Alabama died by suicide following an onslaught of bullying at school, his mother said she finally feels as though she can almost breathe again, now that the civil litigation against her child’s school district has been settled.

Camika Shelby and Patrick Cruz, the parents of 15-year-old Nigel Shelby, settled a civil lawsuit against the Huntsville City Board of Education and the high school’s then-freshman principal, Jo Stafford in March. In her first interview since the settlement, Shelby said she now wants to focus on keeping the memory of her only child alive.

“Nigel was loved at home, but that wasn’t enough, obviously,” Shelby said. “I just want kids of the LGBTQ community, Black kids, all kids really to be able to go to school and feel comfortable and not feel closed in, alone, alienated.”

As a result of the $840,000 settlement reached in March, the Huntsville City Board of Education is required to implement a number of policies aimed at ensuring the safety and security of LGBTQ students in the district.

“First and foremost, we continue to extend our thoughts and prayers to Nigel’s family, friends and school community,” Huntsville City Schools superintendent Christie Finley said in a statement, according to WAFF News. “While we understand nothing can replace the life of a student, it is our hope that the settlement will bring a sense of peace and closure for all involved.”

The agreement also calls for a districtwide electronic recording system where incidents of bullying can be monitored; the hiring of external consultants to advise on best practices and policies to investigate harassment; and the clarification of Title IX policies to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity or sexual expression. The board is required to provide Shelby’s counsel with annual reports for three years demonstrating compliance.

“These cases are not just about accountability. It’s also about trying to make a systemic change to change the culture of the school district,” said Adele Kimmel, Shelby’s lawyer and the director of Public Justice's students civil rights project. “That requires policy changes, training programs, climate surveys and then some way to make sure that all of these things are actually happening.”

Alabama’s anti-bullying policies do not include protections on the basis of sexual identity or gender orientation. As more state legislatures embrace policies that limit or bar gender-affirming care for transgender youth and other restrictive measures for LGBTQ youth, Kimmel said it was notable that an Alabama school district agreed to prohibit discrimination based on students’ sexual orientation, gender identity and sexual expression.

It is possible that future state legislation raises questions about the enforceability of this part in the agreement, Kimmel said, but the other protections of the agreement would remain in effect.

Nigel and concerned classmates approached school administrators about the harassment, which was happening both in school and online, according to the complaint. But, it was only after his death in April 2019 that his mother learned about the harassment her openly gay son had faced. Students allegedly told Nigel to kill himself repeatedly.

Shelby alleged that her child’s concerns were being ignored, according to the civil complaint, and that at one meeting, Stafford told Nigel that bullying was the price he had to pay for being gay and for making “adult” posts on social media about his sexual orientation, according to the complaint.

Nigel’s peers also relayed worries over suicidal thoughts the student was expressing, the complaint said. Stafford allegedly downplayed the serious nature of the conversation, asking reportedly if this was “another one of his episodes where life is getting too hard and things get tough and we want to kill ourselves.”

Stafford and spokespeople for the Huntsville Board of Education did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Shortly after the settlement was reached, school board member Ryan Renaud said “moving forward, I think it’s a process of rigorous implementation and a plan of strategic implementation and working with our staff and administration to make sure that that implementation is consistent across the district.”

It’s a scary feeling, Shelby said, being alone. At 19, she got pregnant with Nigel and left her mother’s house, where she lived with five other siblings. After that, she always had Nigel.

“For the first time ever in my life, it’s actually just me.” The pain of his death is everlasting, she added, but the solitude has sparked a new chapter.

Shelby is working toward a bachelor’s degree in business administration. She is also planning to write a book that grapples with the raw emotions she felt upon discovering her son the day he died.

“I’m Nigel’s mom, but I’m also a person too,” she said. “I was his mom for so long that I forgot who I was outside of that.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com