Here's how 3 students and an abuse survivor changed Ohio State's medical school

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

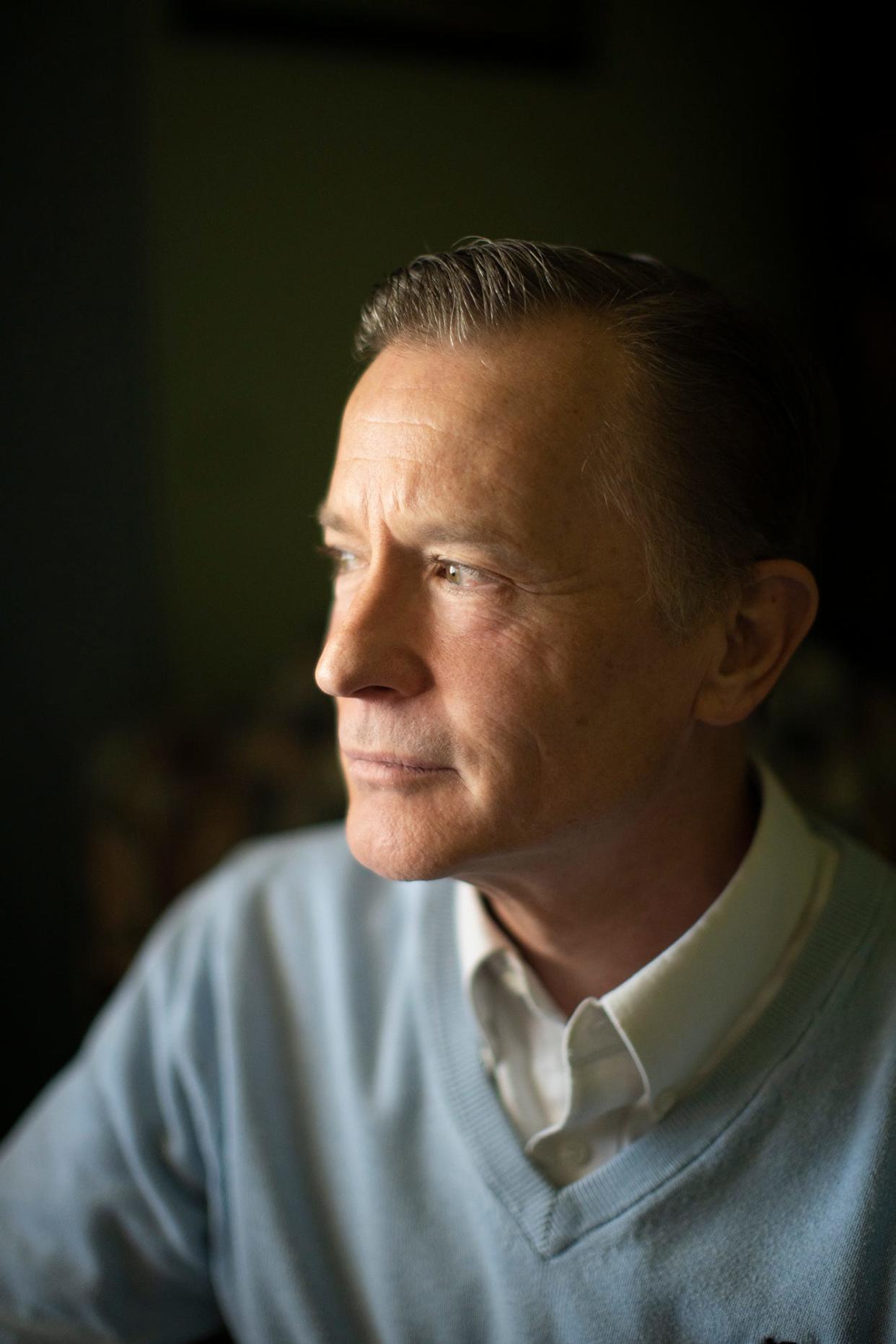

A few steps inside the front door of John-Michael Lander's home sits a wooden case of sports memorabilia faded just enough that visitors can tell the items inside are from a bygone era.

Dangling from red, white and blue ribbons are both gold and bronze medals that Lander won as a young up-and-coming diver while growing up in southwest Ohio. He brought home gold medals at the Norway and Danish cups and was expected to be an Olympic-bound athlete.

But much like Lander's awards from decades earlier, his diving career became frozen in time when an attorney introduced him to a physician who was supposedly one of the best for athletes in Ohio. It was Dr, Richard Strauss, a former Ohio State University doctor, revealed in 2018 by an independent investigation as a serial sexual abuser of students and athletes at the college.

Around 1979, when Lander was 14 or 15 years old, he said Strauss became his primary care doctor.

Lander said Strauss abused him in his medical office and on a few occasions invited him to his home where he sexually assaulted him. Although he was a strong and charismatic world-class athlete, Lander said he'd "go into freeze mode" every time Strauss abused him.

"Your body will take over and you can't move," he said. "It felt like it was an out-of-body experience. My body just departed from itself, and it was like I was watching from above and just watching the whole thing happen."

Strauss, who died by suicide in 2005, is thought to have abused at least 177 former students and athletes, according to university-commissioned investigation by the Seattle-based law firm Perkins Coie. The Perkins Coie investigation also found evidence that Strauss may have abused some high school-aged boys as well, such as Lander.

It's estimated that at least one in every six men have been sexually assaulted, according to the advocacy organization 1in6.

Strauss' abuse tormented Lander for years, even after it ended, he said. While he gave up on a promising career as an athlete due to all that he said he endured, he's turned his recovery into his purpose.

One way he's done that is by working to change the institution that employed the doctor Lander said abused him. A collaboration with three Ohio State medical students that started in 2020 helped Lander move on and has added detailed training on sexual abuse to the medical school's curriculum for the first time.

It's the kind of experience and change Lander said he never imagined he'd be a part of, especially after being abused by Strauss.

"These three women are really trying to break this kind of thing open," Lander said "They're opening the eyes of young medical students, so they realize that there's more than just a statistic in front of them."

For some Ohio State medical students 'enough was enough'

The #MeToo movement began not long after Kylene Daily started medical school at Ohio State in 2017.

Dozens of men had been called out as serial sexual assaulters and harassers across the United States, and it was becoming clear that the medical field wasn't immune to the scourge of sexual abuse. Yet despite the issue's rising notoriety, Daily said other than some brief mentions, training on it was nowhere to be found in Ohio State's medical school curriculum.

So on her own, Daily sought training from the Sexual Assault Response Network of Central Ohio (SARNCO) on how to treat and help victims of abuse. The training was so good, she approached Ohio State professors in 2018 about changing the school's curriculum to add lessons on treating survivors of sexual abuse.

The timing, Daily said, made all the difference as the movement was already forcing faculty to have conversations about how to add sexual assault training for their medical professionals in training.

"I was seeing and hearing from too many friends, too many loved ones that experienced sexual violence ..." Daily said. "Enough was enough for me, and I had a few friends that had very difficult interactions with their physicians, too, so I always knew that I was going to pursue something like this."

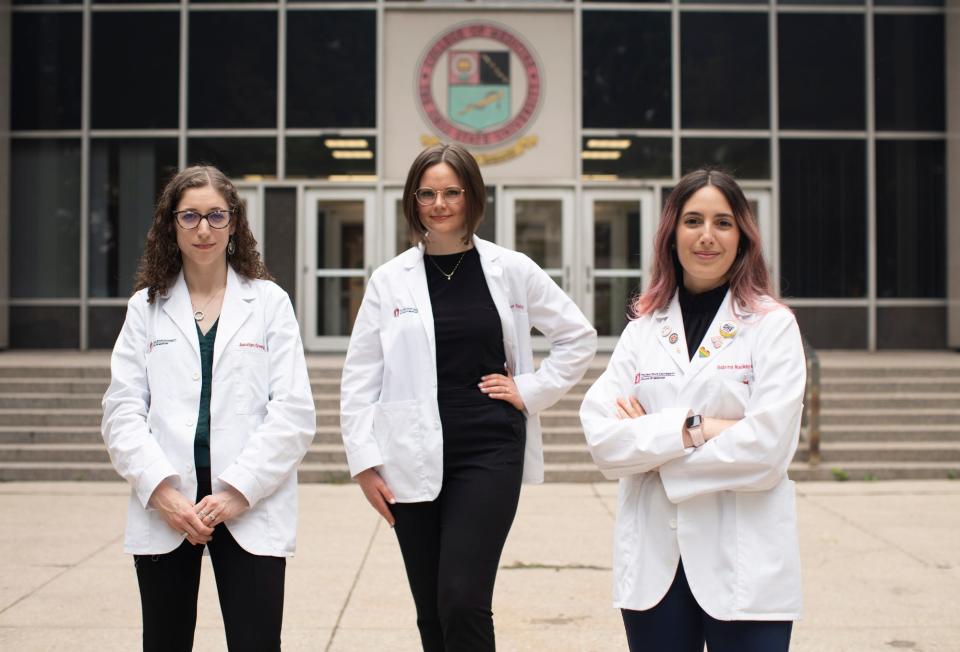

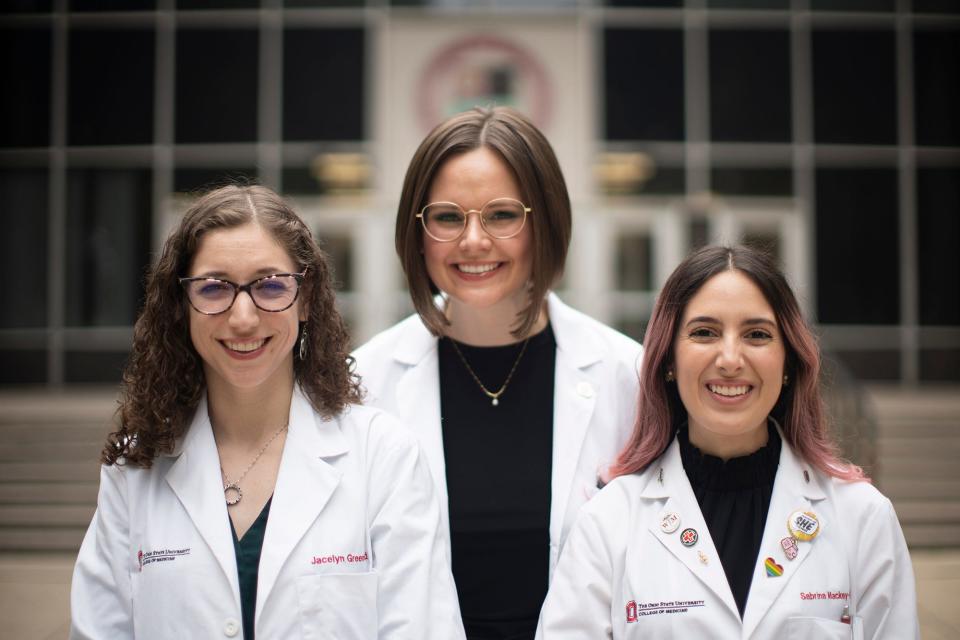

Eventually, Daily met two other medical students who like her were studying to become neurologists: Sabrina Mackey-Alfonso and Jacelyn Greenwald. Like Daily, the two also took an interest in sexual assault awareness and got training through SARNCO.

By 2021, through working with medical school professors and leaders, the trio was able to get many of the curriculum changes they were seeking to be implemented at Ohio State.

The changes include educating students about how common sexual assault is, an examination of cases that went wrong, an exploration of how differences in power affect doctor and patient relationships, and a role-play session where medical students practice standing up to a physician who is accused of wrongdoing.

It also includes conversations with patients, such as Lander, who talk about how they sometimes feel retraumatized by medical professionals who don't believe them or who have little experience and training to treat sexual abuse survivors, Greenwald said.

"We like to keep survivor stories in our curriculum, and we think it's really important for students to hear from them so they can understand the impact that this could have," Greenwald said.

Although the three students were successful at implementing the curriculum updates at Ohio State, they aren't stopping there. The trio is pushing to get other medical schools to adopt the practices so that students at all of the nation's medical schools get the necessary training when it comes to sexual assault.

So far, they've found Ohio State isn't the only university that didn't include the training in its medical school studies. Most others did the same, they said.

"This really was born out of this gap that we saw that we just wanted to fill," Mackey-Alfonso said. "It really was due to our own determination to do this that got it done."

'Not everyone's on board' even after #MeToo movement

Although Daily, Greenwald and Mackey-Alfonso were able to make the changes, they ran into some resistance along the way.

Even after the #MeToo movement, the three said some students openly questioned the need for training on the subject. It was clear, Daily said, that some students were still uncomfortable learning about sexual abuse.

It took a lot of time for most faculty and students to warm up to the idea of a curriculum that included sexual abuse training, Daily said.

"All three of us can still attest that not everybody's on board with this curriculum yet," Daily said. "Faculty has come around, but there are still students that will ask us: 'Why are we learning this?'"

That mentality is one that's existed in the medical field for a long time, said Dan Skinner, an associate professor of health policy at Ohio University's Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine in Dublin.

Nationwide, Skinner said there is little included in medical school teachings about treating victims of sexual abuse, let alone victims of predatory medical professionals.

Like Daily, Skinner said it's baffling that such a topic wouldn't be mandated by now given the wave of abuse scandals that have become public in recent years from doctors like Strauss or Larry Nassar to priests accused in the Catholic Church.

Too often sexual abuse education has historically been relegated to the background rather than being front and center, Skinner said.

One way to change that would be for knowledge of sexual assault training to be included in board examinations for future medical professionals. Doing so would push medical schools to teach about sexual abuse to ensure their students are passing state exams required to become doctors.

Either way, Skinner said it's time for medical schools to begin addressing sexual assault by medical professionals in a "clear headed and honest way."

"If I were a patient — and I am a patient, obviously we all are — I would want to know that this is central to medical education, not just extracurricular," Skinner said.

But, in order to ingrain lessons on sexual assault in medical school education, Skinner said universities need to acknowledge that abusive physicians like Strauss can no longer be considered "one offs" or one of "a few bad apples."

Following the investigation into accusations against Strauss, Ohio State's Task Force on Sexual Abuse, which included a Strauss survivor, researched ways for the university to bolster its support for sexual assault survivors, said spokesman Ben Johnson. Changes include but are not limited to the creation of a new office that focuses on the prevention of harassment and misconduct, enhanced credentialing for Wexner Medical Center employees and required training for faculty and students.

Ohio State's medical school made the changes pushed by three of its students because it's important for future medical professionals to be able to provide trauma-informed care, said Dr. Carol Bradford, dean of the College of Medicine.

"No matter their specialty area, every physician can benefit from training and resources that will help them provide better, more compassionate care and support to vulnerable patients such as survivors of sexual assault," Bradford said in a prepared statement. "I’m proud of these three students for passionately leading this effort.”

Abusive physicians like Strauss are not outliers, a USA TODAY Network investigation published in February found.

From 1980 through 2022, the State Medical Board of Ohio disciplined at least 256 Ohio doctors for sexual misconduct, which is the umbrella term the board uses to describe both abuse and harassment. Of those doctors, 199 sexually abused or harassed at least 449 patients, The Dispatch found in an examination of tens of thousands of medical board records.

After the USA TODAY Network's Preying On Patients investigation published, Skinner said the series should be required reading for medical school students.

"There is no easy way to predict which physicians will become predators," Skinner wrote. "But Ohio’s medical schools can make clear to their students what is expected of our state’s physicians and the consequences for those who violate their oaths."

'A full-circle thing'

When Lander steps foot on Ohio State University's campus, both a sense of unease and triumph wash over him.

He began working with Daily, Greenwald and Mackey-Alfonso in 2020 and came back on campus in 2021 to speak with students as part of a panel. He's done it a few times since then and while the visits give him some anxiety, Lander said they've helped him move on as well.

"It's been like a full-circle thing. ... It was healing for me if that makes sense," he said.

And there was a lot of healing that needed to take place for Lander, who said he's suffered sexual abuse at the hands of Strauss, but also by others.

Lander moved away to attend college at the University of California at Irvine. It was an attempt to distance himself from the pain he suffered in Ohio, but it didn't work.

While out West, Lander attempted to take his own life. Decades later, he'd attempt suicide again after struggling with guilt over the abuse, questioning his own sexuality and reconciling everything with growing up in the Catholic Church, he said.

It's taken years for Lander to get comfortable talking about the abuse. Even now, he sometimes struggles to open up to people about what happened to him.

Still, Lander said he's continued to push himself to open up to help himself recover and to make others more comfortable in coming forward.

He's spoken about his abuse to crowds of people at TEDx conferences. He's written about his struggles and offers himself up for interviews, despite the pain that resurfaces every time.

And he's donated his time to serve as a board member of the Army of Survivors, a Michigan-based nonprofit group dedicated to raising awareness about athletes who are sexually abused.

Nothing though has compared to the kind of catharsis he's experienced by returning to Ohio State to help Daily, Mackey-Alfonso and Greenwald change the medical school.

"To be able to go to the same location where this all happened, and to be able to talk and be heard was beyond any (closure) I could ever think of ..." he said. "When I left, I just felt healed because they heard me. They understood me."

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Strauss victim, 3 Ohio State students worked to change medical school