Here's a look at how RI started celebrating the Fourth of July all the way back in 1777

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

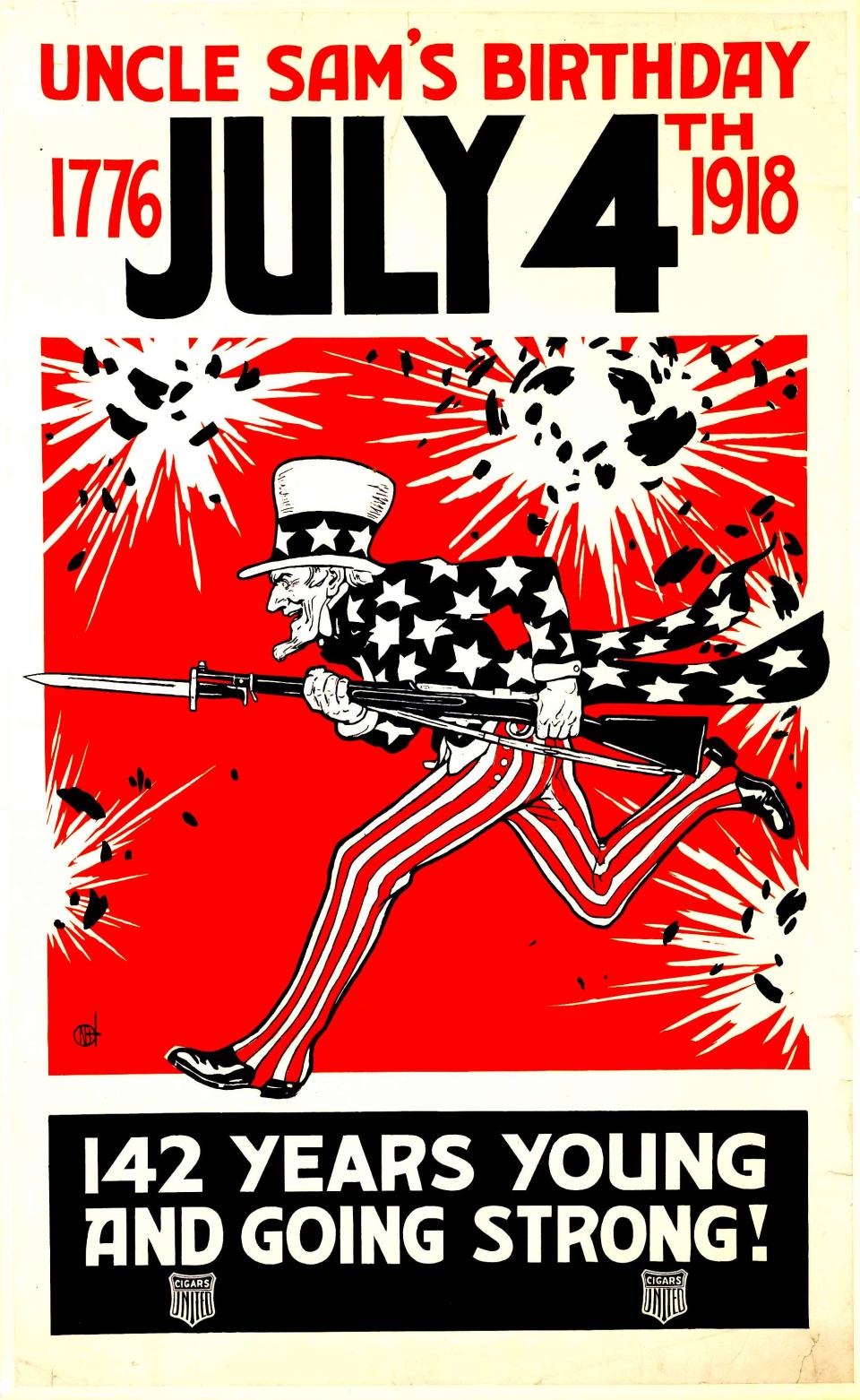

July 4 is not really a military or veterans' holiday. But let’s not forget that our ability to celebrate our independence at all is thanks to those who fought and died to gain it, and then to keep it.

At every military base nationwide, a salute of one gun for each state called a "salute to the union," is fired on the Fourth of July at noon.

Even the earliest July 4 celebrations had a distinctly military flavor, with military bands usually leading the parade. Local military units marched with pride, decked out in their finest garb. Naval ships and shore-based cannons would fire 13-gun salutes.

Little has changed. Consider the famous Bristol Fourth of July Celebration, started in 1785 and acknowledged to be the oldest continually celebrated Independence Day event in the nation. Today’s Bristol parade features floats, high school bands and numerous other participants, but the military provides its beating heart. The Navy has historically arranged for an active duty ship to make a port call, and the ship’s company marches as honored guests in the parade.

All branches of the active military, along with members of the National Guard and Reserves, are represented in the line of march, as are numerous veteran groups.

Early history

As schoolchildren, we were taught that the Fourth of July marks the anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence – arguably the launch point for the United States. Strictly speaking, that is incorrect, because the document was not signed on that day.

The Continental Congress met to discuss independence on July 1, 1776. Congress voted to declare independence on July 2. It was not until July 4 that the final document could be printed and prepared for the signature of John Hancock, president of the Congress.

Although the 56 delegates all eventually signed the document, the date that each person signed is murky. We do know, however, that only Hancock signed on the Fourth.

Some of the more prominent signatories were not even in Philadelphia that day. History shows most delegates signed on Aug. 2, and those who were not present added their names later.

After the July 2 vote for independence, John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail:

"This day will be most memorable in the history of America … I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival ... It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade ... bonfires and illuminations [fireworks] ... from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.”

He was certainly right about the fireworks, but he was wrong about the date. Adams believed so strongly that July 2 was the correct date on which to celebrate the birth of America that he reportedly turned down invitations to appear at later July 4 events in protest.

Early celebrations

There were no fireworks in 1776, but there were the following year.

On July 18, 1777, the Virginia Gazette reported a celebration in Philadelphia that included an official dinner for the Continental Congress, 13-gun salutes, parades, troop reviews and fireworks. Ships in port were decked with red, white and blue bunting.

Roger Williams University Library holds a diary of Mrs. Mary Gould Almy, a Tory (British sympathizer) of Newport. She wrote the following for July 4, 1777.

"This being the first anniversary of the Declaration of the Independency of the Rebel Colonies, they ushered in the morning at [Bristol] by firing 13 cannons, one for each colony, we suppose. At 12 o’clock the three Rebel Frigates that lie at and near Providence fired 13 guns, and at one [o’clock] 13 guns were fired from their fort at Howland’s Ferry [Tiverton]. At sunset, the Rebel Frigates fired another round of 13 guns each, one after the other. As the evening was very still and fine, the echo of the guns down the bay had a very grand effect…”

In 1778, Gen. George Washington authorized a double ration of rum for his soldiers on July 4.

The celebrations grow

Local celebrations took place starting in the early 1800s, and major events were scheduled to coincide with July 4 activities.

According to the website “My Military Benefits,” President Thomas Jefferson announced the Louisiana Purchase to the American people on July 4, 1803. Similarly, the start of work on the Erie Canal (1817) and the groundbreaking ceremonies for the first railroad in the US, the Baltimore and Ohio (1828) took place on July 4. Later in the century, France gifted the Statue of Liberty to the United States on July 4, 1884.

However, average Americans' observance of Independence Day became commonplace only after the War of 1812. In those early years, veterans of the Revolutionary War were the guests of honor, and local newspapers all over the country would name those veterans in their coverage of the event. (In Providence, 29 veterans of the revolution took part in the 1838 procession).

Fourth of July in Rhode Island

In 1785 Rev. Henry Wight of the First Congregational Church in Bristol organized "Patriotic Exercises" in that town. Wight, a soldier in the Revolution, led a procession of townspeople (including a number of military men) to the church. He asked all to remember the veterans who won the war and to express appreciation for the new nation’s freedoms. This activity marked the first Bristol Fourth of July Celebration, which has continued for almost 240 years.

In 1826, four men who participated in the capture of the British armed schooner Gaspee rode in a barouche in a Providence celebration – that’s a fancy carriage that is the equivalent of today’s convertible limo.

The 1853 Providence parade made national news. The Journal reported “ … no object in the procession attracted greater attention than the French carriage which [was] used by General Washington on his visit to Providence.” A 90-year-old Revolutionary War veteran, Abel Shorey of Seekonk, rode inside.

“The carriage is a very curious affair in these days and apparently … had not been used for 50 years.” It was driven by Captain Sharpe, dressed in a full Continental uniform, white-topped boots, buff vest and cocked hat.

What happened to the HMS Gaspee: First blood of the American Revolution or petty revenge?

Observation

The meaning of July 4 is colored by who we are, where we live, and what memories we have from that day.

As an example, consider the residents of Vicksburg, Mississippi. After a long siege, the Union Army finally captured their city on July 4, 1863. Vicksburg did not celebrate the Fourth of July for 81 years after this loss.

Meanwhile, a little over 1,000 miles to the northeast, exhausted Union soldiers contemplated the carnage of Gettysburg, the scene of 50,000 casualties in the previous 72 hours.

On that Independence Day in 1863, our nation was bitterly divided, pitting neighbors, former friends and even family members against each other. Sound familiar?

It pains me greatly to see my friends, brothers and former comrades in arms going at each other like 10-year-olds at recess.

I am saddened that the polarization afflicting our nation has divided us in a way not seen since the Civil War.

This holiday, whether you’re soaking up rays at one of our beautiful beaches or grilling with friends in your backyard, please take a moment to reflect on where we are as a country.

Commit to at least try to focus on those elements of our American life that bring us together rather than the issues that polarize us.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: A history of Fourth of July celebrations in RI