Here's how Milwaukee can reach Mayor Cavalier Johnson's ambitious goal to grow to 1 million people

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood…”

When renowned Chicago architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham uttered those famous words more than a century ago, American cities were in a period of rapid growth.

Today, some cities in the south and southwest are seeing their populations soar. But more than a few proud American cities are shrinking, shedding thousands of residents. Milwaukee is one of them.

Mayor Cavalier Johnson hopes to reverse that trend. More than 100 years after Daniel Burnham’s exhortation, Johnson is making big plans of his own.

He wants Milwaukee to grow. A lot.

During his campaign for mayor, Johnson raised a few eyebrows when he talked about the city increasing its population to one million people, nearly twice its current size.

It is not just that Johnson wants Milwaukee to grow. He needs population and business growth to help relieve enormous pressure on the city’s long-term finances.

But you sense that Johnson’s moonshot for Milwaukee is about more than aspiring to grow; it is about inspiring a city to reimagine itself, to think differently about its future.

More:'We're at the most crucial time': With midterms over, Milwaukee leaders reignite push for sales tax

'The machine shop of the world' was once one of America's largest cities

Milwaukee’s past is a colorful one, filled with periods of industrial innovation and political experimentation. In the first half of the 1900s, the city was known as “the machine shop of the world” and elected three socialist mayors.

It was also, for a time, one of the largest cities in America. Fueled first by German and Polish immigration and later by the arrival of Black families from the south, Milwaukee’s population reached its peak in 1960, when census data showed a city of more than 741,000 residents. That made it the 11th largest city in America. Today, it is 31st. Since 1970, except for a slight uptick in the early 2010s, the city’s population has been steadily declining.

According to the Census Bureau, the city’s population fell 17,600 since 2010 to just over 577,000 in 2020.

In December, the city of Milwaukee filed a formal challenge to the 2020 census count, arguing the Bureau undercounted Milwaukee. It cited a number of reasons, including misplaced prisoners and 2,394 missed housing units. The Census Bureau has since agreed that about 800 incarcerated people were incorrectly counted outside the city, but they have not yet released on a decision on the housing units. After carefully reviewing the evidence, we conclude that a 6,000 person undercount is plausible. Serious concerns remain about undercounts of Black and Latino residents across the country, and it is possible that these Milwaukeeans were undercounted in both 2010 and 2020.

Nonetheless, even if the baseline counts are in error, the direction of population change is more certain. All the best data, including vital statistics and migration flows, points to a population decline in the city over the past decade.

Our review of data since the 2020 census shows that downward trajectory accelerated during the pandemic. From the census in the spring of 2020 to July of 2021, the Census Bureau estimates the city’s population declined another 7,900.

Interestingly, the metropolitan Milwaukee area’s population also fell during the pandemic period, with the Census Bureau estimating a decrease of 9,000 in the metro. That is the first decline in decades. It is unclear if the population loss during the pandemic reflects a temporary or more permanent change in how and where work is being done.

Still, the optics of Milwaukee’s population decline can be deceiving. In some places, it looks and feels like the city is growing. The city saw an explosion of new apartment buildings and condominiums in the last two decades. The apartment building boom continues. Right now, construction is underway on a 44-story tower near the Milwaukee Art Museum. A 31-story apartment building is rising on the northwestern edge of the city’s Third Ward.

The number of occupied housing units in the city increased by 5,000 in the last decade. So, how can our population be declining?

The answer lies in shrinking household sizes in Milwaukee. Most of the new housing units in Milwaukee were smaller apartments with one or two people living in them. Citywide, the typical household size fell from 2.5 in 2010 to 2.39 in 2020.

That change is largely the result of declining birthrates in the last decade. Birth certificate records show that 117,000 babies were born to Milwaukee mothers in the 1990s, falling to 112,000 in the 2000s, and 98,000 in the 2010s.

The shrinking size of the typical Milwaukee household points to the challenges of changing the city’s growth trajectory.

Cities shrink because of two factors: negative natural change—more deaths than births—or net migration.

For now, Milwaukee still has more births than death, although that gap is rapidly closing. But we lost tens of thousands of residents to migration in the last decade.

Many Midwestern cities experiencing population loss over decades

Milwaukee is not the only Midwestern city to lose residents. In the last decade, Cleveland’s population fell 24,000 to 372,000. Only 30 years ago, Detroit had more than 1,000,000 residents. In 2020, it had 639,000, losing another 75,000 in just the last decade. St. Louis’s population declined by 18,000 to 301,000.

Overall growth in the St. Louis, Cleveland, and Milwaukee metros was close to zero.

But population loss is not inevitable for older, Midwestern or industrial cities. After decades of declining population, places like Cincinnati and Buffalo experienced growth in the last decade. Cincinnati added 12,000 residents. Buffalo, 17,000.

Population growth—both city and metro—was even greater in Kansas City, Indianapolis, and Columbus. Looking at just the cities (not the metros), Kansas City added nearly 50,000 residents in the last decade. Indianapolis grew by 67,000. The city of Columbus added more than 110,000 residents.

All three of those cities have several things in common. They have modest gains from international migration. With the possible pandemic-related exception of 2021, they have positive natural change (more births than deaths), although that is slowly dwindling.

What sets them apart from Milwaukee, Cleveland, and St. Louis is domestic migration. While thousands of residents left Milwaukee, Cleveland, and St. Louis in the last decade, thousands more Americans were moving to Kansas City, Indianapolis, and Columbus.

Milwaukee population loss, and growth, varies across the city

Still, the story of population loss in Milwaukee is more nuanced than you might think. It is not a city-wide phenomenon.

We looked at population growth and loss by aldermanic district in Milwaukee (we did this by aggregating census blocks from 2000 into the district boundaries drawn earlier this year). In the last two decades there was significant population growth in three aldermanic districts, the 3rd (east side), the 4th, (downtown) and the 13th (far south side).

The 3rd and 4th districts grew because of strong demand for new housing units being built there. The 13th district grew by increasing its typical household size, likely the result of immigrant families moving into neighborhoods. Together, these three districts added more than 12,000 over the past 20 years.

Another three districts saw modest, but noticeable growth. They were the 5th (northwest fringe), the 8th (near south side), and the 11th (far southwest side). Together, these districts grew by about 4,500 residents over the last 20 years, in large part due to an increase in household sizes.

The 9th (far northwest side) and 14th (greater Bay View) stayed about the same in terms of total population.

The city’s remaining seven districts, all but one on the north side, account for all the city’s population loss. The 15th lost 23% of its population in the last two decades. The adjacent 6th district saw a population loss of 18%, followed by a 15% decline in the 7th, 10% in the 1st, and 8% in the 2nd.

Both the 10th and 12th districts declined 5%.

All told, these seven districts lost 12% of their population since 2000, a decline of 37,700 people. It is the result of shrinking household sizes and decline in the total number of households. Even among the remaining housing units, there are sky high vacancy rates.

The city argues that the 2020 census undercounted housing units in the 6th, 7th, and 15th districts on the near north side. If true, this still would not change the long-term trend. Our analysis shows that the population in these neighborhoods has been declining for decades—down by nearly 55,000 since 1980.

The dueling narratives—population growth and loss—tell us something about the opportunities for growth in Milwaukee, as well as the obstacles to achieving it.

There are plenty of ideas for how Milwaukee can grow again

So, how could the city begin growing again? Here are some ideas popular with leading urban planners, designers, and policy experts. A number of them are already being pursued or explored by Milwaukee’s policymakers.

The city can start by continuing to encourage development where people want to live. Low vacancy rates indicate demand is still strong for housing in the downtown, east side, Walker’s Point, and Bay View areas.

When possible, the city should encourage refugee and immigrant settlement. Parts of the far south side have seen population growth, in large part because of higher birth rates among immigrant families. For example, Buffalo attributes some of its recent population growth to new international arrivals in the city. Given shrinking household sizes among native-born Americans, immigration by larger families is the main way neighborhoods can grow without building more houses.

Milwaukee can increase domestic migration by offering newcomers a city that is more pedestrian and bike-friendly, with more public spaces and easy access to transit options. Zoning changes can increase density in areas that have experienced population loss because of shrinking household size. Where housing is in demand, more of it should be built. At the turn of the 20th century, Milwaukee was one of the most densely populated cities in America. A return to its roots—with better planning—might be in order.

But even doing all those things, important as they are, still will not address the primary cause of Milwaukee’s recent population loss — depopulation of neighborhoods across the north side.

The community, including the broader metro, must reduce racial disparities. The city could stem much of its population loss if more residents — increasingly those of color — chose to remain in Milwaukee. Public investment should be prioritized for neighborhoods that have experienced decades of disinvestment and population decline.

The city should continue to build on the recent decisions by Fiserv and Milwaukee Tool to move their corporate headquarters and hundreds of jobs from the suburbs to downtown Milwaukee. Their relocations and Northwestern Mutual’s recent decision to move jobs from its Franklin campus to downtown serve as a powerful reminder of Milwaukee’s built-in recruiting advantage with today’s employers; the city is more attractive to a younger, diverse workforce, some of whom will want to live in the city, close to where they work.

More:Northwestern Mutual will redevelop an 18-story building by razing most of it. Here's why.

And Milwaukee can play to its other strengths. Our climate and access to abundant freshwater may blunt some of the worst effects of climate change. The quality of life available to middle class families is superior to that in many of the fastest growing cities, where cost-of-living increases outstrip the wages of most workers. For example, a recent study found that Milwaukee was among the most affordable metros for starting teacher salaries.

Still, serious obstacles to population growth remain.

At the top of the list is public safety. The city has seen an epidemic of reckless driving and just recorded its third straight year of record homicides. Perhaps not surprisingly, the areas hit the hardest by the violence in Milwaukee have seen the greatest population decline. While some growing cities such as Kansas City and Indianapolis also have higher rates of violent crime, public safety plays an important role in why people choose to live in a city. It is worth noting that three of the most dangerous cities in America — Baltimore, Detroit, and Memphis — experienced some of the greatest population loss in the last decade.

Without new sources of revenue, Milwaukee will find it difficult, if not impossible, to provide quality services and amenities. And if basic services decline, Milwaukee is a less attractive place to live for current and potential residents who already pay one of the highest property tax rates in southeastern Wisconsin. Many other large cities have more revenue streams available to them.

While Milwaukee offers a variety of educational options for families—public, charters, and vouchers—too many of the city’s schools struggle to meet basic academic achievement standards, a disincentive for families considering where to live.

And finally, is there enough economic growth in Milwaukee to create population growth? As we have reported, metro Milwaukee recovered from the last recession more slowly than some peer cities, with many of the new jobs created in lower-wage occupations. As part of “The American Growth Project,” a recent study from the Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise at the University of North Carolina ranked the 50 largest cities (metros) by speed of economic growth in 2022. Milwaukee finished last.

When we first wrote about stagnant population growth in metro Milwaukee a couple of years ago, some readers wondered whether growth was the best way to measure the vitality of a city.

It is a fair question. In the 2020 census, Pittsburgh was a city of about 300,000 people, less than half the size it was in 1950. It has reinvented itself as a major technology hub and ranks highly in surveys that measure quality of life. A smaller city, the argument goes, does not have to be lesser city.

So, which path should Milwaukee take?

Mayor Johnson is betting on growth. One million Milwaukeeans.

Call it a bold vision for the future or an impossible dream. But if Daniel Burnham—the author of “make no little plans”—were alive today, you suspect he just might be smiling.

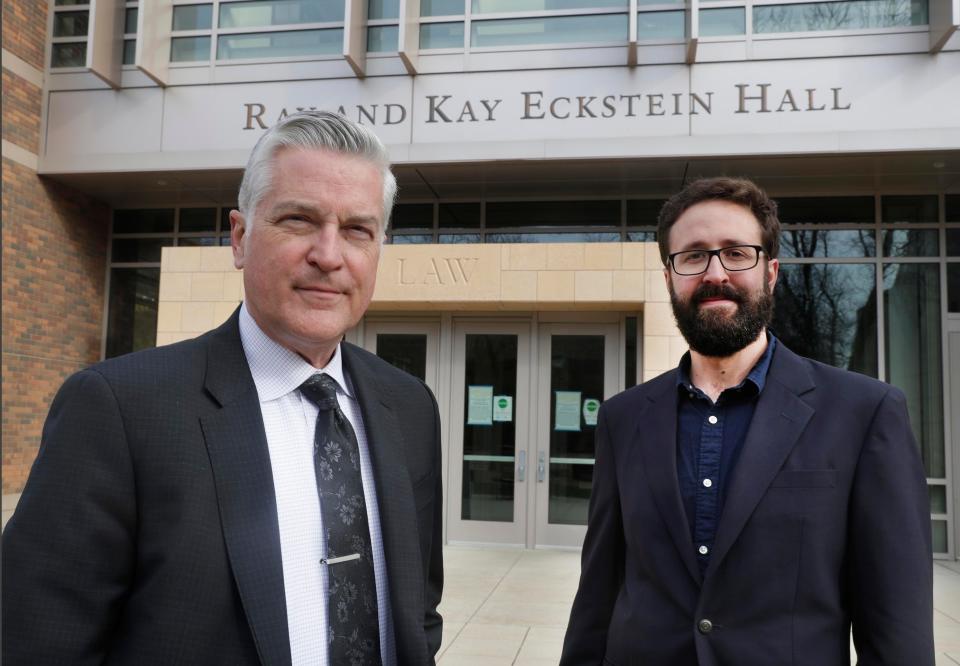

Mike Gousha is a senior advisor in law and public policy at Marquette University Law School. Email: michael.gousha@marquette.edu. John D. Johnson is research fellow at the Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education at the Law School. Email: john.d.johnson@marquette.edu.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: What's path for Milwaukee to reverse population decline, grow again