Here's why jury selection will have major role in Austin police officer's murder trial

When an Austin police officer was charged with murder for an on-duty shooting, an initial attempt to seat a jury proved to be chaotic and unsuccessful.

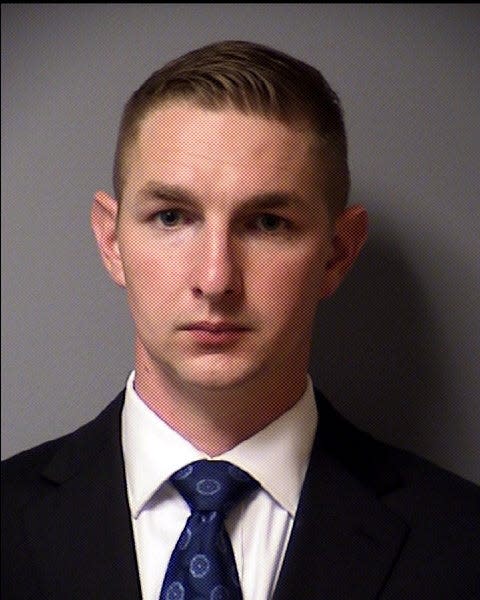

The May jury selection process for the trial of Christopher Taylor was hampered by a shortage of potential jurors, after an entire panel was dismissed when courtroom doors were illegally locked to the public. More potential jurors were dismissed for summer travel plans. After flyers about the case were placed on the cars of some potential jurors — leading to allegations of jury tampering — District Judge Dayna Blazey ultimately declared a mistrial.

On Monday, the court will embark on a second attempt to seat a 12-person jury. Blazey confirmed that three panels of 100 potential jurors — an unusually large pool — would be summoned for the October trial. One week has been set aside for jury selection.

Taylor is on trial for the April 2020 shooting death of Michael Ramos in a Southeast Austin apartment complex. Officers were responding to a 911 call reporting that a person possibly involved in a drug deal had a gun. Police said that after Ramos did not comply with their instructions, an officer shot him with “less lethal” bean bag ammunition.

Ramos got into a car and started driving, police said, and Taylor shot three times into the moving vehicle.

Police later confirmed that Ramos did not have a gun.

Ramos, who was Black and Hispanic, became the local face of Black Lives Matters protests in Austin.

Taylor’s indictment is believed to be the first time an Austin police officer has been charged with murder for an on-duty use of force. The conduct and practices of the Austin Police Department have come under the scrutiny of the office of Travis County District Attorney José Garza, who has secured an unprecedented number of officer indictments.

This is the first of two murder indictments Taylor faces. He, alongside fellow Austin police officer Karl Krycia, has also been indicted in connection with the 2019 shooting death of Mauris DeSilva.

Defense lawyers and prosecutors declined requests to comment on this story, citing a pending motion for a gag order.

Jury selection when an officer is on trial

Jury selection in the case came under further scrutiny when defense lawyers for Taylor filed a motion to move the trial out of Austin, arguing that a fair and impartial jury could not be assembled in Travis County. In September, Blazey denied the motion.

Experts who spoke to the American-Statesman said that, during jury selection, lawyers will try to determine how potential jurors feel about the police as an institution.

“Because it is extremely rare for a police officer to be tried for a crime, there are particular concerns,” said Candace McCoy, a professor at the City University of New York, who has studied how jurors regard police officers.

McCoy said that during selection, prosecutors will likely look for jurors who are “willing to look past the initial trust that a citizen has in a police officer.”

“The likelihood that a person is going to believe what a police officer is going to say on the witness stand is profoundly affected by the attitudes of the family and the community around them,” McCoy said.

In May, the prosecution and defense were each given 10 preemptory strikes, which allow them to excuse jurors without explanation.

Some potential jurors will be excused by the court for extenuating circumstances, such as scheduling conflicts, child care and medical problems. Lawyers can make motions for cause, asking the court to remove a potential juror for bias without using one of their preemptory strikes.

“It’s called jury selection, but in reality, it’s jury de-selection,” said Kacy Miller, Dallas-based jury and trial consultant. During the process, lawyers might contemplate how “experiences and attitudes” might impact a juror’s worldview, rather than “strict demographics,” Miller said.

A mistrial and a motion for venue change

May’s jury selection process was rife with problems, including a shortage of jurors and allegations of jury tampering.

On the first day of jury selection on May 22, members of the public — including reporters and lawyers representing the family of Michael Ramos in a civil suit — were barred from entering the courtroom. Court officials said that the doors had been locked accidentally. Blazey, the judge, dismissed the entire 80-person pool of potential jurors, as public access to trial proceedings is protected under the U.S. Constitution.

The next day, another 80-person panel was called, but those potential jurors had not been told about the duration of the trial, which would likely run for several weeks. Twelve jurors were selected, but four were released due to scheduling conflicts and one was released due to medical hardship.

On the third day, 50 potential jurors were called. Envelopes with flyers inside were found on the cars of three potential jurors. The flyers depicted both Taylor and Ramos, and described the shooting as a murder. No jurors were seated from this pool.

Defense lawyers filed for a mistrial, arguing that there weren’t enough jurors to form a jury. Blazey granted the motion and reset the trial for October.

In July, defense lawyers filed a motion — which ultimately failed — to move the trial out of Travis County, arguing that “pervasive and biased” media attention would make it difficult to empanel a fair jury.

Under Texas law, a defendant is entitled to a change of venue if, in that county, there is “so great a prejudice against him” that he cannot obtain a fair trial.

The motion discussed the dissemination, through social media, of police body camera footage of the shooting. Defense lawyers argued that “thousands upon thousands” of Travis County residents had likely seen the video, alongside “enraged comments” and “charged political speech.”

Former Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore, whose office empaneled the grand jury that indicted Taylor, wrote a statement in support of the motion to change venue.

“In my opinion, if Mr. Taylor were to be convicted by a Travis County jury, there would always be a question of whether he received a fair trial,” she wrote in the declaration.

Prior knowledge of the circumstances doesn’t automatically disqualify a potential juror, according to Patrick Metze, a law professor at Texas Tech University.

“What disqualifies them is if they’ve already made up their mind about guilt or innocence,” he said.

In their response to the motion to change the venue, prosecutors argued that in May, the failure to seat a jury was “unrelated to bias or publicity.” Then, 43 out of 186 prospective jurors said they were familiar with the case. Only 13 said they knew about the case and could not be fair and impartial.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Why jury selection matters in Austin police officer's murder trial