From heroes to 'all of a sudden ... a villain': How online harassment turned to public health officials

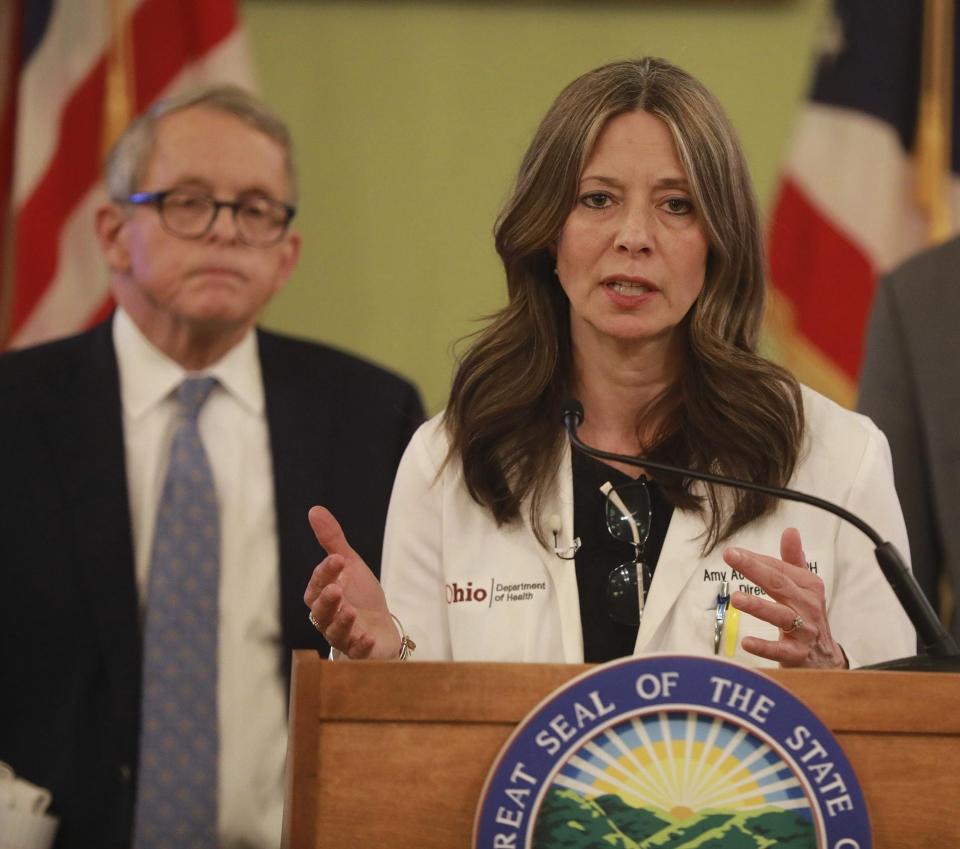

In the early months of the pandemic, amid the flurry of stay-at-home orders, learning social distancing and stocking up on groceries, former Ohio health director Amy Acton faced intense backlash after state guidelines were issued to close businesses and schools.

In June 2020, after lawsuits and protests, Acton resigned. Since then, she has spent time as the director of an initiative at the Columbus Foundation and has been honored by the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for her work during the pandemic.

Unfortunately, Acton's situation was not isolated. In the past year, public health officials have resigned, retired and quit in droves because of the pandemic and harassment that has come along with it – much of it online.

Mysheika Roberts, health commissioner for Columbus Public Health, said she was alarmed by the attacks on Acton and saw similar incidents with members of her staff and others she works with who have been heckled or had law enforcement shadow them because of concerns for their safety.

Roberts said she met with the police department to be prepared for any harassment she might face.

“Just the fact that I had to have that conversation with police made me a little nervous. I was very cognizant when I went places to watch my surroundings, and when possible not go alone,” Roberts told USA TODAY.

The pandemic and mental health: The pandemic changed how mental health is discussed and treated

Hospital workers, vaccine requirement: Over 150 Houston hospital workers are fired or resigned over COVID-19 vaccine requirement

The National Association of County and City Health Officials said that from the beginning of the pandemic until May 2021, it tracked more than 250 public health officials leaving their jobs. Another study showed 20% to 30% of health workers are considering leaving their job, citing additional pressures from the pandemic.

“This shift of your role as a public health official is pretty jarring and probably emotionally a huge step. Being a hero and then all of a sudden you're a villain, that shift was kind of overnight,” said Beth Resnick, assistant dean for practice and training at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Cases of doxxing and harassment

There have been several cases of public health officials being doxxed or otherwise facing online harassment since the pandemic began. Officials in Santa Cruz and Kansas received messages wishing for their death or the loss of their job.

Doxxing – when personal information, like a home address or phone number, is publicly exposed for the purpose of causing harm – has become a grave issue in the era of online "cancellation."

In December, public health officials in Colorado were doxxed by a GOP leader who posted their names and home addresses in a Facebook group along with the message: “Take this information and make your own decisions.” The post was later deleted.

In an August article about doxxing and attacks against public health officials, Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean for public health practice and community engagement at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, noted such incidents have grown rapidly in recent years.

Sharfstein said things got worse in the past year.

“Health leaders have had to fight the pandemic and protect themselves at the same time. That’s been very hard,” Sharfstein told USA TODAY.

Though cases of doxxing aren’t as common, public health workers tend to face a constant, low-level stream of harassment daily on social media, according to Resnick, who said she recently surveyed public health departments across the country.

“In reality what we found from the survey, and talking to people, is that it’s more a low-level type of threat, like ongoing with social media and nasty comments and things like that, versus a much smaller number of people actually going to people’s homes or doxxing them.” she told USA TODAY.

Social media policies

Both Facebook and Twitter, where a bulk of online harassment takes place, have policies that prohibit doxxing and harassment.

Facebook’s privacy policy states that it removes content that shares someone's personally identifiable or private information. According to Facebook spokesperson Jeanne Moran, Facebook uses a combination of technology and teams of people to find and remove content that breaks the company's policies.

Twitter's policy also specifically addresses violent threats, abusive behavior and hateful conduct. Spokesperson Elizabeth Busby said Twitter uses machine learning to take action against abusive content.

Eva Galperin, director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said the origins of doxxing are important in order to understand how it functions and is used today. Doxxing can be traced back to the late 1990s, and Galperin noted that it was originally often used to target marginalized groups and has existed on most social media platforms.

Disparities in harassment

Brooke Torton, senior staff attorney at the Network for Public Health Law, said she saw disparities in her work, with harassment disproportionately affecting women and people of color in the public health field.

“Some of these race-based comments and threats are happening all over the place, and it’s almost like it doesn’t seem as serious as some of those other threats,” Torton said.

After receiving inquiries from public health workers who had been receiving harassment online, Torton and the Law Network created a 50-state survey of existing laws that apply to public health workers and could help protect them.

Torton said some laws are broad enough to cover online harassment and doxxing, but there are still many states that don’t have any laws that protect public health workers.

Combating doxxing and harassment

For Galperin, while most social media companies have policies against doxxing and harassment, she said the extent to which they are followed and content is moderated can vary.

The responsibility to prevent or respond to doxxing and online harassment shouldn’t be on the person who has been attacked, Galperin said, adding that employers should supply more support and anti-harassment training.

“We need to make employers more aware when their employees are likely to be targeted because of the work that they do,” Galperin said.

What's happening now?

A recently passed law in Colorado made doxxing public health workers illegal, other anti-doxxing laws were passed in Nevada and Oregon, and West Virginia is considering a similar law.

Resnick said that anti-doxxing laws are a step in the right direction but that they still leave room for other types of online harassment.

To help prevent harassment, Roberts said there needs to be more education around what public health officials do.

“Our intention is to prevent disease and prevent death, and you cannot have a thriving economy, you cannot have a thriving community if people are sick and dying everywhere," Roberts said. "Ultimately, I hope the endgame is the same for everyone: We want a thriving, vibrant community, and in order to do that we need to be healthy and safe.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Doxxing, harassment, threats: Public health officials targeted online