'Heroic' True Crime Sleuths Helped Identify Hiker Years After His Gruesome Death

This is an excerpt from our true crime newsletter, Suspicious Circumstances, which sends the biggest unsolved mysteries, white-collar scandals and captivating cases straight to your inbox every week. Sign up here.

A true crime filmmaker said she was inspired by the “heroic” efforts of online sleuths who spent years trying to identify a hiker after his emaciated corpse was found alone in the woods.

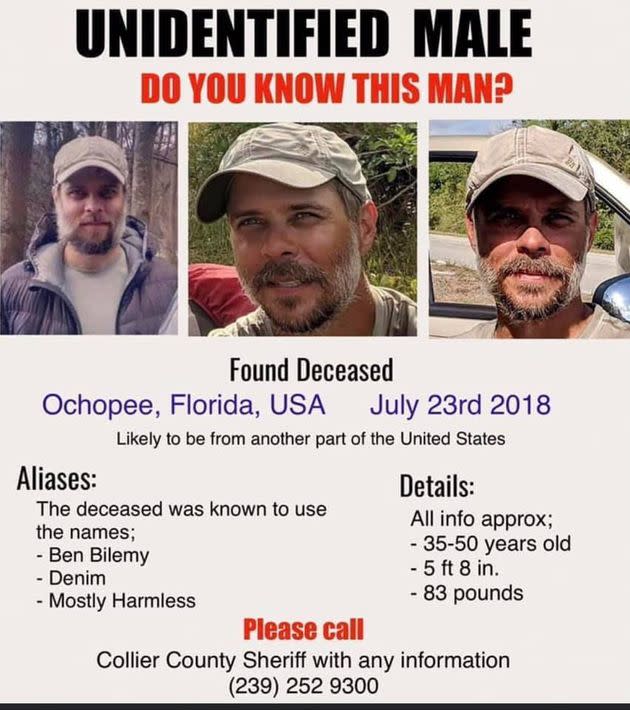

Emmy-winning director Patricia Gillespie’s new documentary, “They Called Him Mostly Harmless,” opens with the finding of a man’s body in a tent near the Florida Everglades in July 2018. There were no obvious injuries or evidence that he had used drugs. It looked like he might have starved to death, but he had snacks on hand and $3,600 in cash — along with two notebooks that seemed to be filled with an indecipherable code — in his backpack. He didn’t have identification, credit cards or even a cellphone.

Facebook sleuths located and circulated a growing number of photos of a hiker who was found dead in Florida without identification.

A growing army of amateur sleuths got to work, sharing a missing flyer and gradually gathering photos shared by hikers who had encountered the man on the trail. Their numbers grew after Nicholas Thompson’s 2020 Wired article on the “internet mystery” went viral. The hiker never shared personal details or his name — most knew him by his “trail name,” Mostly Harmless. He turned out to be anything but, which the Facebook moderators featured in “They Called Him Mostly Harmless” discovered after devoting two years trying to find the name of a John Doe who didn’t want to be found.

Gillespie told HuffPost in an email interview that she was fascinated by the determination of online sleuths to identify Does. She also explained why she chose to center “Mostly Harmless” around two Facebook group moderators, Christie Harris and Natasha Teasley. Despite their contentious relationship and warring Facebook groups, Gillespie was struck by the “generosity” and “endurance” both shared in trying to solve this case.

How did you find Christie and Natasha?

The short answer is — I Facebook-stalked them. The longer answer? I work a lot in what’s commonly referred to as the “true crime” space. Truth be told, I’ve always bristled at that label — which is a longer conversation — but a few years ago, I started asking myself why.I began to pay attention to a lot of the discourse surrounding the genre — and a large share of it was critical or diminutive. What really got under my skin was not that they were criticizing us — the makers — but they were criticizing our audience. I felt that was really out of touch, and if I were to be honest, a little sexist. The “true crime community” is overwhelmingly female — and I think, like a lot of things women gravitate to — that somehow makes it easier to dismiss. There’s an attitude that “true crime girlies” (another label I don’t love) are somehow lacking in empathy — that they’re morbid, intellectually lame, shallow, or — paraphrasing something our protagonist Christie once said to me — “fat sad old ladies with nothing better to do.”

Christie Harris moderates a Facebook group that helped identify the man featured in "Mostly Harmless."

I know for a fact that’s not true. When I am making a film, my goal is not to tell the story of “a crime” — but rather to tell the story of people engaged in the struggle to become the heroes of their own lives in extreme circumstances — a crime or a mystery is often that “extreme circumstance” — but the real story, the thing that grabs me, is an examination of how we as people can look into the face of something bleak or tragic or “evil” and maintain our goodness, our humanity, our fight. I think the true crime audience, by and large, feels that too — and despite what others may think — their engagement with “true crime” is an exercise in empathy. It’s deeper and more sophisticated than meets the eye.

I wanted to make a film that celebrated that community, that looked at what was motivating them. Who better to examine than people who are so committed they choose to be not only spectators — but actively try to help. The research period for this film was remarkable in that you could look back through these Facebook Groups and almost travel back in time to watch the case unfold. You could see what people were feeling or doing on a daily basis. It was in this phase it became very clear to me that Christie and Natasha were both leaders. These are very hardworking women, with big responsibilities, who nevertheless donate their time to try to help people — because the tragedy of the unidentified moves them. They want to live in a world where the unidentified get to come home, and they’re fighting to see that world. To me that’s heroic, and fascinating to explore what motivates their generosity, their endurance.

When did you realize Christie and Natasha’s adversarial relationship would become sort of foils/narrative centers — at least in my interpretation; please let me know if you disagree — around which much of the film would revolve?

It’s interesting you use the word foil. One of the things that really grabbed me while I was making the film was how much these women had in common — not just that they were two individuals who donated their time to solve unidentified persons cases, but similarities in terms of their socioeconomic class, tight family structure and mental health. And yet, the internet had somehow pitted them against each other. I think what we tried to depict in the film is less about a conflict between them, and more about what it’s like to live online. What we can and cannot see about each other in the digital space.

Natasha Teasley, who moderated a Facebook group trying to identify a dead hiker, said "it was a gut punch" when the online sleuths found out his true identity.

Can you clarify who “solved” the mystery? In the film, it seems like Christie received the first photographs and shared them with police but Nick Thompson wrote in his second Wired piecethat he received a tip that Rodriguez had been identified. Or did it all play out sort of simultaneously?

As Natasha says, this case was solved by the collective effort of thousands of people. The people we featured in the film were surely leaders of that effort. “Who solved it” is an unanswerable question in my opinion. I really do believe the distinct efforts of Christie, Natasha, Nick, [DNA lab] Othram and the CCSO [Collier County Sheriff’s Office] were all needed to identify him. But yes, multiple people “hit” on the same day.

We’ve seen how dangerous internet sleuthing can be in terms of misidentifying and harassing innocent people and their families (and in the case of Mostly Harmless, people who are alive and obviously not him). Your film highlights something I’ve never thought about before — how potentially harmful it can be for the sleuthers themselves, particularly as it relates to their mental health. Do you think these harms outweigh the benefits (e.g., crowdsourcing/crowdfunding) of internet sleuthing?

I think sleuthing is, ultimately, an act of altruism — I don’t think it’s at all harmful in and of itself. The type of things you see Christie and Natasha going through are not connected to “sleuthing,” in my opinion, so much as the internet being a nasty place. People feel a certain liberty to behave cruelly or irresponsibly online, and that can do legitimate harm. There’s a feeling it’s not “real life” — but as we all increasingly live our lives online, we have to realize — it is. You can do real harm there. So in summary: yes, of course the benefits of sleuthing outweigh the harm, but it’s important to take care of yourself out there while you try to do something good. And of course, important not to be an a**hole.

To simplify/follow up on that: From your perspective, is internet sleuthing ... mostly harmless?

I think it depends on who’s at the keyboard.

“They Called Him Mostly Harmless” premieres Feb. 8 on Max.