He's been on TV for three decades. Here's the side of Phil Williams you don't know.

She saw him at a walk to raise money for Alzheimer's research.

She thinks it's funny now that she had never seen him before. She didn't recognize the white hair, the intense eyes, his direct manner of speaking.

The first time they actually met was online.

Their first date was in 2016 at a Catholic Mass. He was in so much pain then, and he was in need of some spiritual inspiration. So church was the perfect place.

It wasn't too long before he invited her to dinner. They went to the San Antonio Taco Company in Nashville.

They walked in together, and the people in the restaurant began to chant.

"They were saying 'Phil, Phil, Phil,'" Cheryl Williams said. "What is happening? I'm a private person, and this was not private at all."

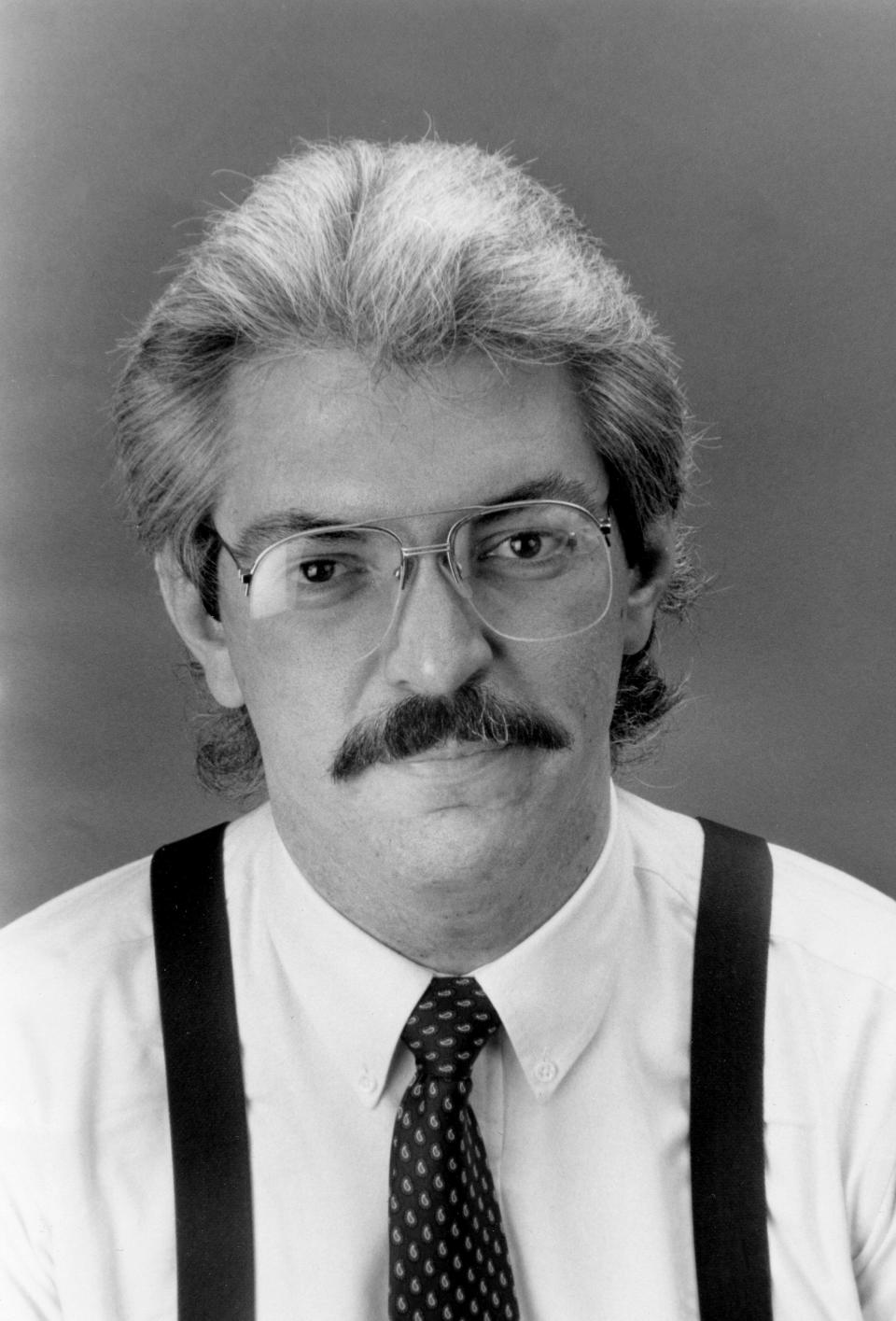

Public attention is part of the package these days with Phil Williams, a confrontational investigative television reporter who has become somewhat of a lightning rod in Middle Tennessee. In November, Williams was honored with the John Chancellor Award for Excellence in Journalism at Columbia University. He's been in Nashville since 1986, including the last 25 years at NewsChannel 5.

Williams, 62, a Pulitzer Prize finalist as a young reporter at The Tennessean, has been the target of public affection and public scorn.

In his house, he's got a poster-sized card that says "A VERY BIG THANK YOU! PHIL" signed by some of the residents of Franklin, where he did recent reporting on the mayoral race, including stories about candidate Gabrielle Hanson's unfounded and controversial comments about the Covenant shooting, her connections to white nationalists and her use of social media images of "supporters" Williams discovered she didn't know.

Sitting at his kitchen table, he plays a voice message: "Phil, you're an enemy to the people. You're a propagandist. You're a left wing progressive (expletive), who lies and manipulates people's minds to further your (expletive) stupid left wing agenda. You're a piece of (expletive), Phil. People like you need to be eradicated. We're done with people like you. You're an enemy to the people. You're an enemy to this country, and an enemy to our freedom, Phil. We will deal with you eventually."

His life has been a life full of trauma, so death threats aren't as intimidating as some of the situations he's endured.

In the midst of turmoil, he says he's healthier now than he's ever been.

And he gives a lot of thanks to Cheryl, who suggested therapy and convinced him to convert to Catholicism.

"She doesn't live in my world," he said. "She's not a news junkie. She's not a political junkie. She keeps me grounded."

Their lives have become a test of compatibility, public vs. private.

Growing up poor

Phil Williams grew up knowing something was wrong.

His father, Roy, was a taxi driver with a temper. His mother, Faye, was a stay-at-home mom with a temper.

"There was a lot of yelling in my home," Williams said. "It was a dysfunctional environment."

When the taxi salary couldn't sustain the family, Williams' dad went to see the local political boss in Columbia, Tennessee, where Williams was born and raised. After their meeting, Roy Williams was given a job as a prison guard.

"He slipped him (the political boss) a little cash," Williams said. "I had a sense of this isn't right as much as a child can have that sense."

When Williams was 10 years old, both his grandfather and uncle drank themselves to death in a three-month period. Their deaths launched a lifelong battle with alcohol, although Williams, himself, has only been a social drinker and said he never had a personal problem with the bottle.

Looking back on the traumas in his life, alcohol seemed to haunt him.

His interest in journalism began in the early 1970s.

"I was a child of Watergate," Williams said, recalling that he watched television coverage of the scandal that led to the demise of the presidency of Richard Nixon. "I was absolutely enthralled by the Watergate hearings."

Depending on the kindness of strangers

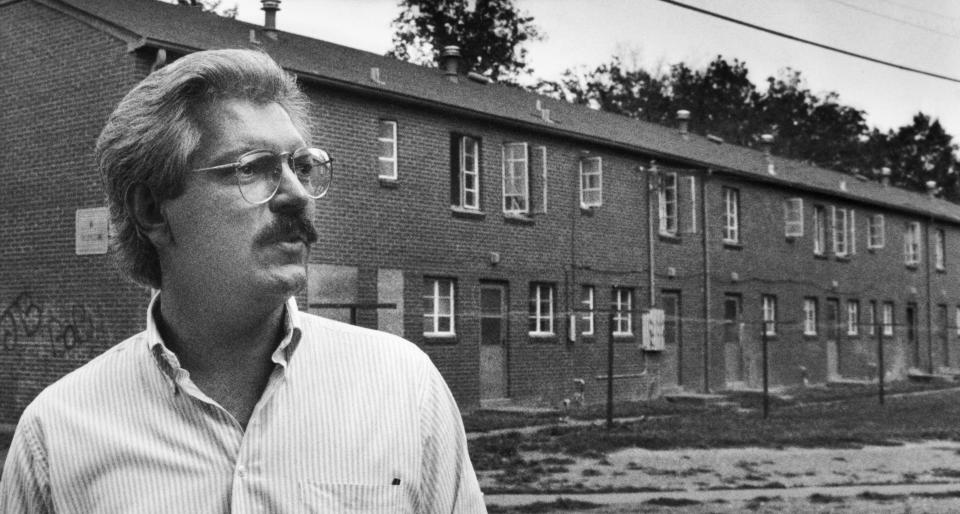

The Williams family moved to Nashville in 1979, into what he called "the worst housing project in the city."

The Sam Levy Homes were not safe, and he said he was known in his teenage years as "the poor kid." He said he was jumped by a group of kids selling dope.

"They knocked me down and started kicking me," he said. "I ran down the street crying the whole way."

He remembers going to local churches and asking for food.

"There were times I was not sure where a meal was going to come from," said Williams, who later wrote about the Sam Levy Homes in a moving story in The Tennessean. "We ate a lot of pinto beans. It took me many years to be able to eat pinto beans again."

Williams felt so embarrassed about his family's poverty that when he asked for rides from high school friends, he would walk blocks away from his real home and be waiting on the porch of a nicer place to be picked up.

"Poverty is my No. 1 fear," Williams said.

Still, he was valedictorian at McGavock High School, and he became editor of the school newspaper.

In quick succession after high school, he got a job as a bank teller and got married at age 19. In 1981, after two years away from school, he started at Middle Tennessee State University, where he worked on the college newspaper.

As would become a theme in his young life, while he was thriving as a journalist, his personal life was falling apart.

"When you marry that young, neither of you know who you are," Williams said.

The marriage ended after six years.

A journalism career begins

In January 1986, Williams was on his way to work as a reporter at Florida Today in Cocoa Beach when he saw the Space Shuttle Challenger explode in the sky above him.

Suddenly, the young journalist was thrust into one of the biggest stories in U.S. history.

One day, he "got his butt kicked" on a story by a competitor because, he said, he didn't ask the right question.

He vowed to always put effort into his questions from that point forward. And those direct, sometimes uncomfortable questions, have become part of his reporting style.

Williams started at The Tennessean in 1986, jumped to television at WKRN in 1992 and then went across town to NewsChannel 5 in 1998. The jump to television was a surprise because as a newspaperman, Williams had criticized TV news for years.

Still, Williams said, he was drawn to the power of television. "I had become what I despised," he said.

The recent John Chancellor Award was for his cumulative achievements. His notable stories have included:

A Tennessean investigation in 1989 into the world of charity bingo games which revealed political corruption, organized crime and a multi-million dollar scam. His work on the investigation with colleague Jim O'Hara was a finalist for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize in Public Service.

Confrontational interviews when he exposed employees playing slot machines in the breakroom of the Davidson County Clerk's Office (on St. Patrick's Day).

An investigation into state police allowing drug smugglers to enter Tennessee and distribute drugs, while waiting to arrest them so they could seize (and keep) the drug money on the way out of town.

A three-year investigation at NewsChannel 5 into former Tennessee Gov. Don Sundquist and millions of dollars in state contracts that went to the governor's friends. That investigation won the Peabody Award, one of three he won.

And, most recently, several stories about Franklin alderman and mayoral candidate Gabrielle Hanson, which drew the attention of television host John Oliver who praise Williams as "Nashville's nosiest (expletive)."

Many of Williams' most memorable television moments involve confrontation.

Once, he exposed a judge who was working at another job at a funeral home while people were waiting for hours in his courtroom.

"He came running across the parking lot, and I thought what the hell is happening," said Judge Gale Robinson, who found himself confronted by Williams. "I ain't perfect. Y'all ain't perfect. I admitted I was wrong."

Robinson said he received a "private reprimand" from the judiciary, and he no longer works at a second job during court hours.

And he respects Williams.

"He has a job to do," Robinson said.

Robinson's wife died in 2023, and he got a call from Williams.

"He asked me how I was doing," Robinson said. "He said, if you ever want to talk, give me a call."

William's former reporting partner at The Tennessean, Jim O'Hara, described him as "dogged."

"He does it with old fashioned shoe leather," O'Hara said. "He is always watching. He would see something and start digging. The lawmakers realized they couldn't snow Phil."

O'Hara, who retired from a government job in 2016, said Williams brings value to his community.

"Nashville is better for him still doing reporting the way he and I were brought up to do it," O'Hara said.

Al Tompkins, a teacher at the Poynter Institute and former TV news executive in Nashville, said Williams is fearless.

"Fantastic to Phil and Channel 5 for not being intimidated," Tompkins said.

He said Williams never chooses "style over journalism." With Williams, "the substance overwhelms the style," Tompkins said.

Tragedy at home

In the mid-1990s, Williams met a "young and attractive" attorney, who was doing some work for an agency he had been investigating.

Her name was Peggy Nance Catalano, and they were married in 1997.

She was fun and smart, and she had a serious drinking problem, Williams said.

"Being a child of alcoholics, I was inclined to believe I could fix her," he said. "You really want to save the next alcoholic in your life. At her best, people loved her. At her worst, she hated herself."

He said she stayed sober during her pregnancy. Jackson, their son, was born in 1999.

"Four days after he was born, she fell off the wagon," Williams said. "I remember rocking my son, crying myself, trying to figure out how I was going to get through this."

She began getting drunk driving convictions and was fired (for public drunkeness) from her job as the executive director of the Registry of Election Finance.

It wasn't long before Phil Williams' detractors began ripping him for his wife's problems.

"You're battling at home to save someone you love," Williams said. "Then you're attacked in public for standing by that person."

He remembers when his wife told him she wished she had cancer.

"People understand cancer," he said.

By January 2016, they were still married, but living separate lives.

She would pick their son up on weekends to take him to piano lessons.

One Saturday, she didn't show up.

Williams went to her house and found her dead.

"I reached a rock bottom emotionally," he said. "I was sitting at my desk, crying at work."

'All the difference in the world'

A few months after she died, Cheryl Williams' grandmother also died after suffering from Alzheimer's disease.

She had been her grandmother's caregiver. So she went to a walk in Nashville to raise money for research.

That's when she saw and later met Phil.

Cheryl Williams, 49, knew quickly he had "a tragic past." She said he was suffering from PTSD, and she suggested a therapist.

"I thought there's no way he could be this good and wholesome," she said. "But he was. Therapy has made all the difference in the world."

She went with him as he converted to Catholicism.

She is his third wife, and she's now comfortable with his public persona. "Although, I don't always watch him," she said with a laugh.

"I think his job is noble," she said. "It's tied into my faith. It's doing the right thing no matter the cost."

She agreed with him that he's healthier now than he's ever been.

"He's my hero and my confidant," she said.

"He's my everything."

Reach Keith Sharon at ksharon@tennessean.com.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Phil Williams at NewsChannel 5: Williams talks trauma, career