'Hey, hey, they're subversive': Micky Dolenz sues for release of Monkees' FBI records

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Last week, The Monkees’ Micky Dolenz filed a lawsuit to retrieve his records — and not the wax kind that spin on a turntable.

As the Washington Post reported Aug. 30, Dolenz has sued the Justice Department to have his and The Monkees’ unredacted FBI files and any related files made public — a redacted version came out 10 years ago.

Yes, J. Edgar Hoover and his mid-’60s G-Men surveilled The Monkees back in the day because they thought the band was subversive.

They were correct.

From 1966-68, The Monkees commanded the two most important media platforms of their era: radio and television (plus a whole lot of Tiger Beat covers).

And they made use of the opportunity to — in today’s parlance — groom children (and some teens and adults) with progressive political philosophy.

Predictably, online reaction to Dolenz’s lawsuit drew the standard derisive and dismissive comments Monkees fans such as me have become accustomed to hearing and rebutting. This time, the haters scoffed, too, at the notion that The Monkees were in any way political.

But the redacted file released a decade ago describes The Monkees as “four young men who dress as ‘beatnik types.’” It describes their concerts as using video to project “subliminal messages … depicted on the screen which, in the opinion of (redacted), constituted ‘left wing innovations of a political nature.’” These included anti-war and pro-civil rights messages.

For what it’s worth, here’s yet one more attempt to defend my “first band,” most of which is drawn from a column I wrote in 2006 when “The Monkees” television show reached its 40th anniversary.

Santa Claus is retiring:Peyton Manning wants to take over and 'rub it in Brady's face'

‘Talented singers, musicians, and songwriters’

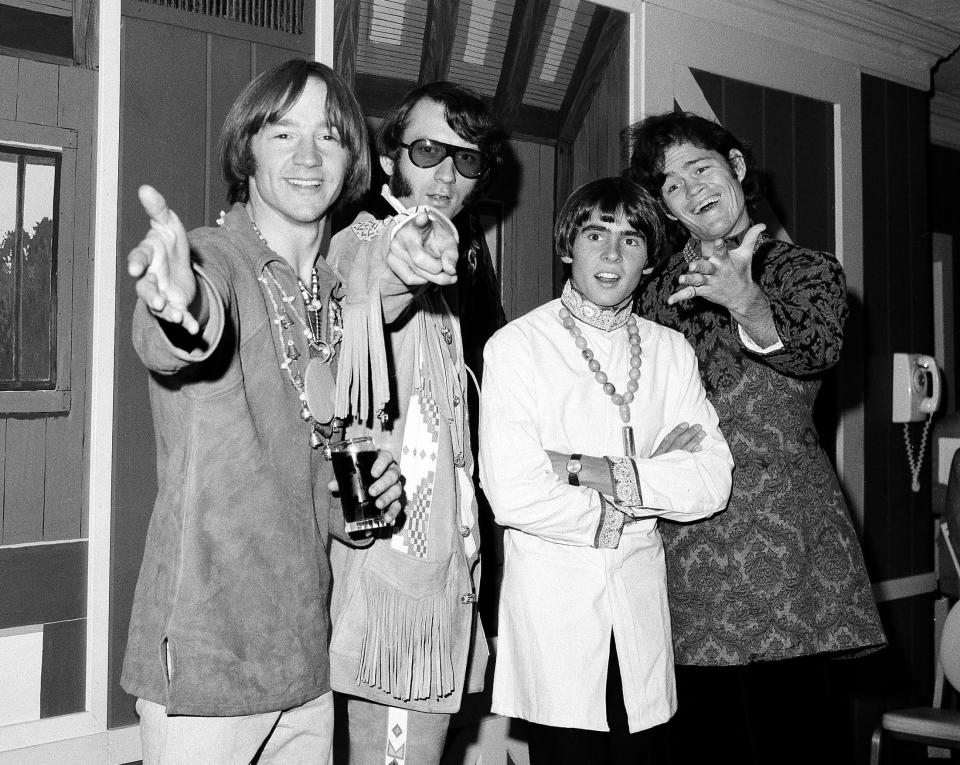

As Eric Lefcowitz points out in “The Monkees Tale,” there were two “Monkees” — the characters on the television show and the musical quartet made up of the real-life Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Michael Nesmith and Peter Tork.

Beginning in the 1960s, some critics and members of the public scorned The Monkees because studio musicians played on their albums and singles, including providing virtually all the musical backing for the first two albums.

This ignores the fact that contemporaries such as The Grass Roots, The Association, The Mamas & the Papas, Sonny & Cher, and The Beach Boys all drew from the same stable of session musicians for some of their recordings.

The good news is that a re-evaluation of The Monkees’ music has occurred since I wrote this column in 2006.

The respected All Music Guide, for instance, has changed its tune. Back then, it wrote, “It would be foolish to pretend, however, that they were a band of serious significance, despite the occasional genuinely serious artistic aspirations of its members.”

Now, The Monkees’ entry says, “The Monkees were talented singers, musicians, and songwriters who made a handful of the finest pop singles of their day (as well as a few first-rate albums) and delivered exciting, entertaining live shows.”

Different drum:Monkees’ Nesmith pivotal to country-rock

As innovators, they were the first pop band to use a Moog synthesizer, and Nesmith’s Monkees songs and productions contributed to the creation of country-rock as a genre. Eventually, The Monkees wrote their own songs, played their own instruments and toured as a credible rock band.

And they had hip taste: The Monkees booked The Jimi Hendrix Experience to open for them on their summer 1967 tour. Alas, Hendrix was too much for The Monkees’ young fanbase, and he played only seven shows before dropping out of the tour.

‘Monkee vs. Machine’

The television show always has fared better with critics. John Lennon was a fan, comparing its humor to that of the Marx Brothers, and the series won two Emmy Awards in its first season, for outstanding comedy series and for directing in a comedy series.

“The Monkees,” however, was marketed as a children’s show (worked on me when I found the show in syndication in the ’70s), but its humor and visual techniques often broke ground for the medium.

“The Monkees” broke the fourth wall and allowed characters to address the audience directly, for example, improvisation played a large role in the filming of the scripts, and most pop culture historians credit the show with inventing the music video in its weekly “musical romps” — short films set to a Monkees song.

Thematically, the show’s humor provided teenagers and adults with political and social commentary, beginning with the sampler that hangs on the wall near the front door of their “pad”: “Money is the root of all evil.”

The plots regularly put The Monkees in the position of defending what was right, which usually pitted them against authority.

In “Monkee vs. Machine,” for example, Tork foils the attempts of an efficiency expert to replace an old toymaker with automation to improve profits at the expense of quality and creativity.

‘We’ve got something to say’

To be sure, the majority of The Monkees’ songs belong to the love song genre, but a subversive perspective also carried over into The Monkees’ music and was present from the beginning: On “(Theme From) The Monkees,” Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart write, “We’re the young generation, and we’ve got something to say.”

The Monkees’ song choices and original material would back that up time and again.

A year before The Beatles told the world “All You Need Is Love,” Tork co-wrote “For Pete’s Sake,” a hippie anthem with the same message. The song became the closing theme for the television show during the second season and perfectly encapsulated The Monkees’ pro-youth point of view: “In this generation, in this lovin’ time, in this generation, we will make the world shine.”

Despite such optimism, however, The Monkees also acknowledged the confusion that social change wreaks, with Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil’s “Shades of Gray”: “I remember when the answers seemed so clear. We had never lived with doubt or tasted fear.” Tork’s plaintive delivery of the final line of the chorus, “Only shades of gray,” vividly captures the song’s sense of uncertainty teetering on despair.

Gerry Goffin and Carole King’s “Pleasant Valley Sunday” kicks off with a classic guitar riff — played by Nesmith — and then deconstructs the malaise of “life” in “status symbol land” — the suburbs: “Rows of houses that are all the same, and no one seems to care. ... Creature comfort goals, they only numb my soul and make it hard for me to see.” (Personal historical note: Goffin and King wrote the song after they moved to my hometown, West Orange, N.J., and named it for one of the main roads, Pleasant Valley Way. It was a much better place to grow up than how they portray it, and, frankly, the song is more relevant in today’s world of look-alike suburban sprawl subdivisions than it was in 1967.)

In concert, The Monkees encountered the sort of adulation and screaming that The Beatles experienced, and with “Star Collector,” they cut celebrity worship to pieces by exposing how “young celebrities” view their groupies: “How can I love her when I just don’t respect her? ... It won’t take much time before I get her off my mind.”

In other self-referential songs, The Monkees agitated in favor of themselves on Nesmith’s “Listen to the Band,” but also satirized themselves on “Ditty Diego — War Chant,” from the “Head” soundtrack: “You say we’re manufactured. To that, we all agree. ... Hey, hey we are The Monkees. We’ve said it all before. The money’s in, we’re made of tin. We’re here to give you more.”

“The Door Into Summer” delivers a double whammy, one against war profiteering and one against avarice in general: King Midas sits “in his counting house where nothing counts but more,” counting the “fool’s gold” he’s made from “a killing in the market on the war.” Outside his window, “the echo of a penny whistle band” forces him to realize “he pays for every year he cannot buy back with his tears.”

On the television show and on their records, The Monkees made several oblique and direct references to the war in Vietnam. Throughout the television series, for example, Tork’s character advocated pacifism with lines that appear in hindsight aimed at the escalation of the war in Vietnam.

Although some confusion exists over what Boyce and Hart knew when they wrote “Last Train to Clarksville,” they intended it as an anti-war song. One account says Clarksdale was the original name of the town, but the two songwriters changed it to Clarksville before they recorded it. Later, they learned Clarksville, Tenn., is home to Fort Campbell, an Army base from which soldiers shipped out to Vietnam. Even with that bit of serendipity on their side, the key line in Boyce and Hart’s song addresses the anxiety of soon-to-be-deployed soldiers: “And I don’t know if I’m ever coming home.”

“Zor and Zam” tells the story of two kings who agree to have a war, and through all their preparations, it looks as if it’ll be a really splendid war. Instead, “The war it was over before it begun. … Two little kings playing a game. They gave a war, and nobody came.”

On Dolenz’s “Randy Scouse Git,” the narrator adopts the voice of authority and sings, presumably to a counter-culture youth, “Why don’t you hate who I hate, kill who I kill to be free?”

The Monkees’ most strident socially conscious song, however, is Dolenz’s “Mommy and Daddy,” where the writer and singer lets loose with a series of questions he wants his preteen listeners to ask their parents: “Ask your mommy why everybody swallows all those little pills. Ask your daddy why that soldier doesn’t care who he kills. ... Do you think I’m too young to know, to see, to feel, or hear? My questions need an answer, or a vacuum will appear.” It’s about as far from bubble gum as you can get, and that’s the tame, released version.

By then, however, no one was listening. After the television show was canceled in 1968 and left the air that September, The Monkees never hit the Top 10 again and their records sold fewer and fewer copies. A shame, because The Monkees did in fact have something to say and they still do. Go ahead and listen to the band.

And while you’re at it, FBI, release the full file on The Monkees.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: FBI should release Monkees files, finally prove band was subversive