How They Hid the Bomb: 75 Years After the Trinity Nuclear Test

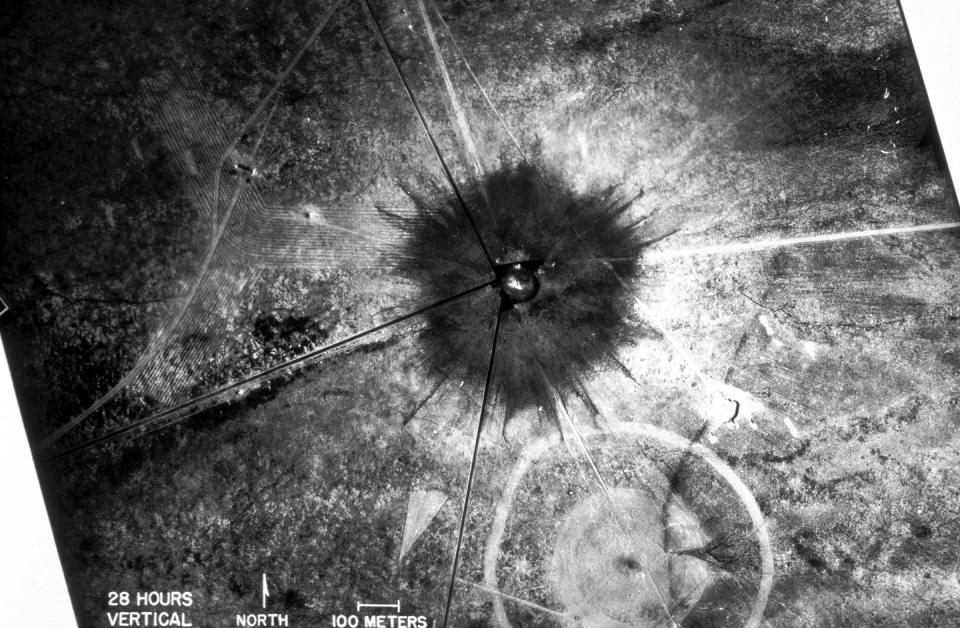

This story was originally published in the August 1985 issue of Popular Mechanics. It's been visually updated for the 75th anniversary of the Trinity Nuclear Test that took place on July 16, 1945. This test was the world's first look at the power of the nuclear bomb.

Fierce thunderstorms and unpredictable winds had kept Norbert Deare awake late into the sweltering summer night. He had helped batten down the filling station near Socorro, N.M., the night before, thinking there might even be an overnight flood. About 5:30 the next morning, Deare's worst fears seemed trivial as he was thrown out of bed by an apocalyptic explosion far more frightening than the worst thunder he'd ever heard.

"The state police said it was an accidental explosion at the Army camp," Deare told an interviewer in documents released to Popular Mechanics by the Defense Department under the Federal Freedom of Information Act. "But it seemed more like the end of the world."

That explosion, which took place seconds before 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, was, perhaps, the most significant event of the 20th century.

Yet it was almost a month later before the people who witnessed it, and the rest of the world, learned of its true importance. They had witnessed the explosion of the first atomic bomb.

Despite the fact that hundreds of scientists and thousands of support per sonnel had moved practically overnight into a sparsely populated part of the country, despite the strict security surrounding an enormous canvas-colored device that moved for days along the New Mexico prairie on a train; and, though the first A-bomb blast shook buildings all the way to El Paso, Texas, the War Department managed to keep the bomb a secret.

How they built the bomb is a story that will be told over and over again during this, the 40th anniversary of the atomic era. But how they hid the bomb may be an even more spectacular tale.

Even today, hundreds of documents relating to the first A-bomb test remain locked away under secret classification. Still unavailable are several documents relating the results of radiation tests following the test blast at what is now the White Sands Missile Range. Also still under wraps are correspondences that might shed light on how much information leaked during the weeks between the test and the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima in August 1945.

Among the startling facts uncovered in our investigation:

Dozens of documents that had been available to the public but were never used suddenly became classified sometime in the 1970s.

The governor of New Mexico in 1945 was not informed of the nature of the test until after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima the next month.

FBI agents visited the publishers of several major newspapers the day after the test to quash potential stories that might raise questions about the test.

Defense Department officials who have acknowledged that three different stories were prepared to explain the test to the public actually had prepared a half-dozen explanations. Among those not revealed until now was an explanation to cover civilian deaths in the Alamagordo, New Mexico, area. (In the end, the simplest explanation was released since no deaths were involved.)

The security set up around the A-bomb development and test had a very composed and easy appearance, from the front gate to the dozens of labs where the bomb was being built. Beneath the genteel surface, however, stood a hard-as-nails network to protect the secret. Dorothy McKibbin typifies this security network.

''When newcomers arrived, it was my job to make them feel comfortable, get them located and not answer any questions," Mrs. McKibbin told us in a brief interview. In the two years before the first A-bomb was exploded, she was the official greeter at Los Alamos, the northern New Mexico mountain town where the A-bomb was developed. Mrs. McKibbin's job was to greet personnel arriving at the research camp and direct them to their quarters. Anyone arriving without orders was to be directed away by Mrs. McKibbin, now in her eighties.

Keeping a Secret

To get an idea of how hard it was to keep the secret, consider the speed at which the Los Alamos compound grew. When the Army took over the 54,000acre site in 1942, the local population was under 250, including the faculty and students of the Los Alamos Ranch School. By the time the bomb was ready to be tested, the Los Alamos population hovered around 7,000. Directly or indirectly all worked for the Manhattan Engineering District, an Army unit whose name evolved into The Manhattan Project.

Besides Los Alamos, the district itself also included uranium-processing facilities in Tennessee and Washington state. The two areas combined had fewer than 30,000 residents before the Manhattan Project, but by August 1945, nearly 90,000 people lived and worked around the two facilities.

Under the direction of General Leslie Groves, who headed the Manhattan Project, security gradually came under the control of a special detachment headed by Major John Landsdale. The FBI, which had worked closely with the War Department's Counter Intelligence Corps in the first year of the project, began working directly with Landsdale in 1943, when security became his responsibility. The CIC had poor communications with the FBI, according to newspaper reports written over the past 20 years.

In addition to sheer numbers, Groves had to contend with scores of expatriate German scientists and with some American scientists who had shown sympathy to the Soviet Union.

Groves was under White House orders to develop the bomb quickly. The Manhattan Project did, in fact, yield a nuclear explosion less than three years after it was organized. To work at such breakneck speed, normal security checks would not be possible. Not only that, but it was impossible to check deeply on scientists who had escaped Nazi Germany. Groves settled on the simplest solution to each security problem, reasoning correctly that the more elaborate the security, the more attention would be drawn to Manhattan Project activities.

Standard security forms were used on new personnel. These would reveal names of friends, associates and organizations to which the applicant belonged. The FBI provided the Manhattan Project security people with backgrounders on all incoming personnel. Jobs were separated as much as possible so that no one person working on the project would know what another person was doing. For the most part, there were no security breakdowns. But the one that got away was explosive.

German-born and English-educated physicist Carl Fuchs was arrested, after the bomb was developed, for passing secrets to the Russians. Neither court records nor documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act shed light on what Fuchs told the Russians, and he never publicly revealed his activities.

Keeping the press out of the picture was a major headache. Probably because there was a war on, the press was more cooperative than might be expected. Words like "atomic energy" were banned successfully from news stories. If a local Texas newspaper picked up a story that might reveal something about the A-bomb project, it stopped there. A Chicago newspaper, for example, would be barred from reporting the news to its readers.

On the day of the blast at Trinity Test Site in New Mexico, a Chicago resident was traveling through New Mexico by train. He felt the blast and saw the sky light up. At the next stop, according to one published account, he raced to a telephone and called a Chicago newspaper. The traveler thought he had witnessed the fall of a giant meteor. The reporter wrote a brief article and filed it with the city editor.

The next day, when she returned to work, FBI agents were waiting for her in the publisher's office. They explained to her that she should forget the story, and it never appeared.

Explaining the Blast

Any accounts of the blast on July 16 were based on the terse news release finally issued by Los Alamos. It read:

"Several inquiries have been received concerning a heavy explosion which occurred on the Alamogordo Air Base reservation this morning. A remotely located ammunition magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics exploded. There was no loss of life or injury to anyone..."

The true story would eventually be told, but only after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. To help provide the public with a credible account, the Manhattan Project allowed New York Times reporter William Laurence to live on the Los Alamos compound in the months leading to the blast. He kept the secret and wrote a celebrated series in the Times after Hiroshima.

In the days before the blast, Jumbo a 180-ton steel container for testing the A-bomb-had to be moved under canvas wraps across the New Mexico desert to the Trinity Test Site. It rode on a specially designed, 200-ton freight car. Even the military policemen riding with the train knew nothing of its contents. They were told that it would be used to store high explosives.

However, the container's unmistakable ballistic shape showed through the canvas, and many legends emerged. The most preposterous had it that the Army was working on a secret submarine in the desert.

How the government hid the A-bomb in New Mexico from even those who lived next door already is an intriguing story. When the remaining documents are released, it may prove even more exciting.

You Might Also Like