Hidden for decades, Bergen soldier's concentration camp relics now on display in New York

Salvatore and Frances Distefano found the cherry wood double dresser at a North Jersey furniture showroom soon after their wedding in 1952.

Over the course of a 62-year marriage, the dresser would be a fixture in their Ridgefield Park home. It was where Sal stuffed his undershirts and Frances stashed her jewelry and porcelain doll collection and where the Distefanos' only daughter, Nina, posed for photos on her own wedding day.

It was also a holder of secrets.

The bedroom dresser had a hidden compartment, under the middle set of drawers, where Salvatore stored the relics of his Army days, a time he rarely spoke of.

Distefano, a Jersey kid from West New York, served as a medic in the 120th Evacuation Hospital unit with Gen. George Patton's Army during World War II. The 120th helped free Buchenwald, the first and largest concentration camp in Germany, where the Nazis killed more than 56,000 Jews and other prisoners.

More:Woodcliff Lake teacher suing over suspension after Hitler lesson, 'discriminatory acts'

Buchenwald was a hell on earth for the 280,000 detained there, a place of starvation, torture and disease. The Americans found a ghost town of emaciated survivors and corpses. "Nothing has ever shocked me more," Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote after reaching the camp.

Salvatore spent three months at Buchenwald after its liberation in April 1945. To his family, it was a black hole in his life, barely mentioned.

But he kept artifacts from his time at the camp, hidden for decades in that cherry wood cabinet in the house on Teaneck Road. Discovered by chance four years ago, the collection of photos and mementos went on display this summer in the Museum of Jewish Heritage in lower Manhattan, part of an exhibit chronicling the horrors of Nazi concentration camps — and the soldiers who freed them.

"His exhibit paints a picture of what it was like to be a liberator," said Rebecca Frank, a museum curator.

'It was a horror scene'

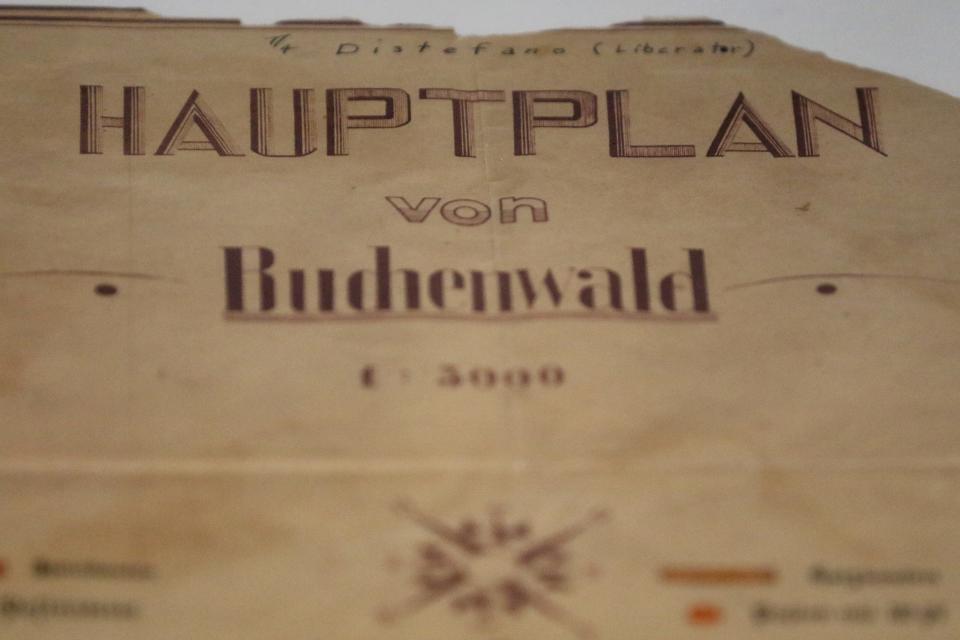

Among the items Distefano stored in his bedroom was a working map of Buchenwald, which listed guard positions around the camp. There was also "Buchenwald and Beyond," a 1946 book retelling the experiences of his unit. Distefano is credited as one of its photographers.

Dozens more photos were in the secret drawer, including one of Distefano sitting on a fence in Buchenwald, shoulder-to-shoulder with his army buddies, his helmet cradled in his hand. The picture, blown up to life-size, is on display at the museum.

The Distefano siblings — Dan, Nina and Paul — always knew that their father served in Germany during the war. They knew he assisted in surgeries. But they didn't know much more, because their soft-spoken father rarely mentioned his experience.

"Whenever I asked him to talk about it, he said `No' and that was the end of that," said Dan Distefano, a musician and public school music teacher who lives in Englewood.

Nina, a retired nurse now living in River Edge, heard about her father's wartime activities only when she was an adult. "Winds of War," a 1983 television mini-series, triggered a rare outburst, she recalled.She remembered a "fairly graphic" scene of Nazis marshaling people into gas chambers.Her father grew agitated. "That's exactly what it was like!" he exclaimed. Nina was shocked, and urged her dad to say more, but the silence returned.

More:NJ man's daring escape from Nazi slave labor is the subject of a documentary

There were other moments when Distefano revealed bits and pieces of his war days. German prisoners "looked like skeletons. It was a horror scene," his daughter recalled his saying. "He told me once, `It was so horrendous that your eyes are seeing it but your brain can't comprehend it.' It wasn't something he wanted to think about."

"There's so much power to unpack here about how liberating Buchenwald impacted his life," said Frank, the museum curator. "This idea of not wanting to speak about the experience is widespread among liberators as well as survivors. A lot of it is about trauma."

A secret compartment

When Salvatore died in 2014 at age 90, the Distefanos assumed their father's wartime stories were gone with him.

But that changed in 2018. An assisted living facility where Frances was living asked Dan for his mother's living will. Frances suggested her son check the "secret compartment" in the dresser. It had an extra space "where we always hid things," she told her son.

A surprised Dan checked the dresser and discovered the stockpile of his father's artifacts. "It was my dad's time capsule, hidden from 1952 so that it could finally tell the story he had been unable to tell."

Dan immediately called his siblings. "We all agreed that we should donate them to a museum so that people could learn from them," he said.

More:‘Moved to tears’: Paterson educator describes workshop at Japanese internment camp

They were most struck by the map, which their father had torn down from a headquarters at Buchenwald.

In the upper righthand corner, he had written in his neat handwriting in pen, "Technical Sergeant Fourth Grade Distefano."

One word followed: "Liberator."

"That was how he saw himself and his role in history," said Dan. "He wanted people to know that he was there and what he saw and that he helped end that reign of terror."

Growing up, Salvatore had planned to become a doctor. He started college but was drafted in late 1943, at the age of 20. His unit entered Buchenwald on April 4, 1945, and, after spending time there, moved on to Cham in eastern Germany. Disfefano treated American soldiers there as well as concentration camp prisoners who'd been sent on "death marches" as the war neared its end.

Returning home, Distefano abandoned plans to pursue a medical career. "Maybe it was because he was traumatized by his experience," his son said. Instead, his father earned an engineering degree, working first for American Standard, the plumbing company. He met Frances at a dance around 1949. Three years later, they were married.

'He was just a kid'

On a recent day, the Distefano siblings ambled through the exhibit at the museum, viewing the various displays. When brother Paul spied the cabinet, he stopped in his tracks, His hands flew up to his face.

"It's an amazing thing to see something you grew up with in a museum," he said, tears welling in his eyes.

Nina stood in front of the oversized photo of her father, transfixed by the smiling young face that stared down at her from a wall.

"He had to be 21 years old there," she said. "I can't get past the fact that he was just a kid when this happened."

She gestured to the American flag folded neatly into a triangle that the family had donated to the museum. "He was always very proud of his service," she said, as her daughter, Kristin Picone, wrapped her arms around her. "He knew that he did something important."

More:In wake of controversial Hitler essay, Tenafly unveils Holocaust education program

Several months ago, Nina posted Salvatore's photo on Facebook, noting proudly that her father was a liberator of Buchenwald. A friend she's known for more than 40 years soon called her and revealed something he had never mentioned.

"My father was a prisoner in Buchenwald," the friend said in a choked voice.

"If it wasn't for your father, I wouldn't be here."

Deena Yellin covers religion for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to her work covering how the spiritual intersects with our daily lives, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: yellin@northjersey.com; Twitter: @deenayellin

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NJ soldier's Holocaust artifacts now in New York museum