Will this hidden gem become a tourist attraction? How park status could affect Chiricahuas

CHIRICAHUA NATIONAL MONUMENT — This crown of volcanic rock pinnacles rises above southeastern Arizona grasslands and oak-pine foothills, a largely unknown attraction far from the name-brand national parks that draw millions to the American West each year.

Now, there’s a plan to change its image by changing its name — and its status — from Chiricahua National Monument to Chiricahua National Park.

“I couldn’t believe it when I was here last night and there were (only) two other cars,” hiker Michael Boulter said, after stepping off the monument’s shuttle from a trailhead to the visitors center on a Tuesday afternoon in June. His morning ride up the monument’s eight-mile scenic drive had been on an otherwise empty van, and he had not seen another soul while enjoying nine miles of trail.

The relative seclusion within a 40-mile-long mountain range, once inhabited by the Chiricahua Apaches, remains a getaway mainly for those in the know, possibly numbering no more than 130,000 people a year, according to the National Park Service. For the sake of a burgeoning tourism economy in small towns around the mountains, Arizona politicians and regional boosters hope to draw more attention and traffic by redesignating the 12,025-acre wonder to make it America’s 64th national park. The change would help it stand out among 424 monuments, lakeshores, parkways and other sites managed by the National Park Service.

Visting Chiricahua was a far different experience than Boulter, a “view chaser” from Kalamazoo, Michigan, had encountered at Arches National Park, the previous destination on his western trip. That sandstone spectacle outside of Moab, Utah, was "so flooded with people" it required timed permits for entry. The story is similar at other famous sites adorned with the “national park” moniker far north of Chiricahua. Grand Canyon National Park, about a seven-hour drive from Chiricahua, attracted 4.7 million people last year.

If Congress approves, Chiricahua would become the first national park atop one of Arizona's Sky Islands, a chain of biologically rich and diverse mountain ranges that extend north from Mexico. Also called the Madrean Archipelago, these forested "islands" towering over a sea of desert grasslands are a mixing zone for migrating birds and mammals from the Rockies and Sierra Madres. They attract birders from across America, and at least one jaguar that has set off camera traps as it traversed the mountains in recent years.

The zone faces renewed pressure from mining companies and from a changing climate that could push some species off the mountains. Fire, including one that burned across most of the national monument a dozen years ago, is a constant threat to pine and spruce species living at the edges of their natural range.

Creating a park would require Congress to act

Putting Chiricahua on the national parks map could buoy gateway motels, restaurants and wineries 35 minutes away in Willcox.

“Obviously, you get more exposure when it’s a national park,” said Greg Hancock, a Willcox city councilmember. He moved from Safford to Willcox and bought neighboring motels that had previously closed, hoping to capitalize on the potential he saw when wine-tasting rooms and festivals energized the sleepy Interstate-10 town. He refurbished one motel and is working on the second, both of which stand opposite empty warehouses and near an empty car showroom. “I’d like to see the town grow,” he said.

New crowds streaming to Chiricahua might also deter solo wilderness seekers like Boulter.

“It’s beautiful,” he said, just as it is. “One of the things I really like about it is it flies under the radar.” He said he would prefer national park designations to prioritize preservation, not profit.

Unlike national monuments, which presidents can create on their own under the Antiquities Act to protect landmarks and landscapes of historic or scientific interest, national parks require congressional authorization. The U.S. Senate approved a Chiricahua National Park bill last year, but the House did not act on it before that session ended.

Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Arizona, announced in March that he had reintroduced the bill with cosponsor support from Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Arizona. Rep. Juan Ciscomani, R-Arizona, introduced companion legislation in the House. All three touted a national park’s ability to boost tourism in the region. If approved this year, the legislation would create Arizona’s fourth national park, after Grand Canyon, Saguaro and Petrified Forest.

Dedicated in 1924 and still featuring rock trail work completed by the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps, Chiricahua National Monument protects wildlands and a broad sprinkling of rhyolite columns and balanced rocks, also known as hoodoos, eroded from the tuff deposited 27 million years ago by a volcanic explosion. A chartreuse layer of lichens clings to the taupe pillars. More than eight-tenths of the monument is congressionally designated wilderness, meaning roads and mechanized travel are generally forbidden beyond the scenic drive, a campground and a visitor center.

Local families who had sought monument status to drive tourism called this part of the mountains the “Wonderland of Rocks.” The Apaches called it the “Land of Standing-Up Rocks,” according to the National Park Service.

Congressional support: Sen. Mark Kelly, Rep. Juan Ciscomani team up to make Chiricahua National Monument a national park

A new level of protection for the landscape

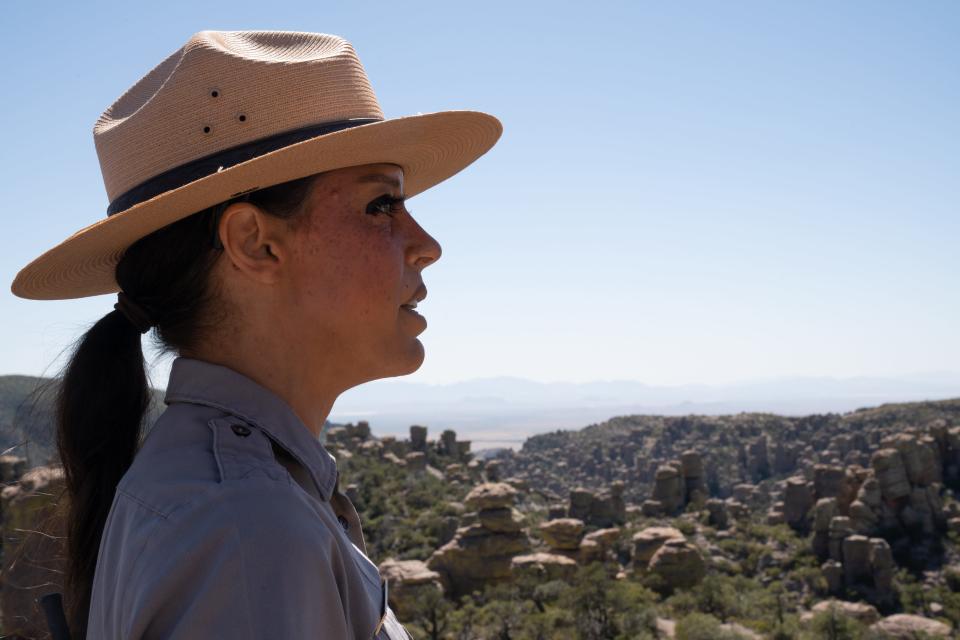

The monument is a “hidden gem” among the national parks and monuments systems, said Tiffany Powers, head of interpretation, education and visitor services for the National Park Service’s Southeast Arizona Group. Only 50,000 to 65,000 people pass through the visitor center in a given year, she said. The monument does not charge an entrance fee or track every visitor, though, and managers assume at least another 50,000 to 65,000 people enter the park but skip the visitor center.

Most of those visitors come in February and March, Powers said, coinciding with the region’s busy birdwatching season. “You can have the park to yourself the rest of the year,” she said.

While the National Park Service takes no official position on the legislation, Powers said, she and others on the monument’s leadership team would welcome the chance to greet more visitors. “What are we preserving this for if people can’t come here and enjoy it?”

Park status would also confer a greater level of protection to the land, Powers said. Management priorities wouldn’t change, but dissolving or shrinking a national park would require an act of Congress. Though reductions to national monuments are rare, former Republican President Donald Trump downsized two Utah monuments that Democratic presidents had created.

Not much is likely to change immediately if Congress redesignates Chiricahua as a park, Powers said. The legislation does not increase funding for the monument or increase its staff of 33. That could change over time if more visitors hear about and visit the park, causing the agency to redistribute funds to keep up.

There’s little developable area to make significant changes. Managers plan to upgrade camp and picnic sites, but don’t have room to add or widen roads. That could change if private lands nearby become available for sale, Powers said.

Where to travel: Top 10 state and national parks around Arizona that aren't Grand Canyon

Not everyone wants a national park nearby

The monument’s compact stature and limited development are reasons some neighbors are skeptical of a park designation. Doubts appear strongest on the east side of the Chiricahua Mountains, opposite the monument’s west-side entry. There, around clusters of homesteads for birdwatchers and night-sky aficionados at the hamlets of Portal and Paradise, some believe they already have their hands full with visitors. It’s a place where people consider the lack of cellphone service an amenity.

“I don’t need any more business,” said Reed Peters, who bought a Portal lodge catering to birdwatchers shortly after he came birding himself in the 1990s. Called Cave Creek Ranch, his business rents rooms and cottages under a canopy of oaks and sycamores in a habitat favoring numerous birds rare to the U.S., including the elegant trogon, a red-white-and-green birder magnet that’s more common in Mexico and Central America. His outpost at the base of Cave Creek Canyon is connected to the monument’s entrance via a narrow gravel road that winds over the mountains through Coronado National Forest and closes in winter.

“The thing that might save us is that the road is so bad,” Peters said.

Local Cochise County services such as EMTs also are scarce in the area, he said, and hiking trails on the U.S. Forest Service lands surrounding the monument are in rough shape. The creek grows algae in summer, he said, nourished by human waste because there are inadequate restrooms. “Nobody here has the staff to deal with more people.”

Mostly, Peters said, the monument itself doesn’t have space to handle more people.

“It’s totally inappropriate for the scale of the place. It works very well the way it is.” He mentioned Massai Point, a commanding viewpoint over the rock spires, and the place most roadside visitors stop for a look when the monument road tops out.

“You can’t expand the mountaintop,” he said. “That’s all there is.”

Still, “You can love an area to death,” said Rick Taylor, a naturalist, author and birding guide. He moved to the east side of the Chiricahuas after he fell in love with the mountains while working as a fire lookout in the 1970s. Through various jobs he held at the monument, he had an arduous but enjoyable daily commute via dirt bike, hike and bicycle left chained in the forest. It was the kind of place he could leave a bike chained to a tree and no one would notice or take it. Making it a national park could change the intimate place he loves, likely disappointing some of the newcomers because there’s no room for upgrades within park boundaries, he said.

“I’m sure we’ll get spillover visitation to this side of the mountains,” he said, noting the likely effect on Peters’ lodge. “It’ll just mean there’s a longer waiting list at Cave Creek Ranch.”

'There's not a lot up there'

Across the mountains in Willcox, though, local officials are all in on the park idea. They began writing to the congressional delegation to press their case two years ago, City Manager Caleb Blaschke said. Having built a tourism reputation on wine grapes and the throng of sandhills cranes that descend on a nearby playa each winter, he said, Willcox is ready for the next step. “We think we’ll get increased visitation to our community.”

“Most people associate the word ‘monument’ with something small,” Blaschke said. But when people arrive and “see all those pillars and start hiking see all the wild turkeys and deer, it’s a totally different thing than you thought it was going to be.”

Some locals who enjoy the Chiricahua Mountains say they’re eager for the business but not necessarily new traffic to their favorite campsites.

“I love Turkey Creek,” said George Burkert, referring to a recreation zone south of the monument. His wife, Janet, agreed, but said she has little use for the monument, especially because there are few campsites and they cost more than camping on the nearby national forest.

“There’s not a lot up there. To us, the monument is: Drive up the road and look,” she said. "It's not my place to go to."

If a national park attracted more people, though, it could benefit the couple’s buy-sell-trade shop, Willcox Traders, which occupies a prominent downtown corner on the intersection where motorists turn south toward the Chiricahuas. The shop sells everything from greeting cards to dishes, books, used vacuum cleaners and live chicks. The couple said a tourist once bought a young goat from them and rented a truck to get it home.

The rock formations are worthy of national park preservation, hiker Dayton VanAcker said while passing through the monument’s Echo Canyon Grottoes, where shaded recesses in the rhyolite open onto dramatic views of the spires. But the rocks alone aren’t what had drawn the young man from Mesa to Chiricahua 13 times and counting.

“I come looking for the rattlesnakes,” he said. An amateur herpetologist who also studied reptiles in college, he enjoys photographing snakes. VanAcker spoke after just missing his chance to photograph a banded rock rattler: He and the snake had startled each other on the trail.

The Chiricahuas have a unique assortment of animals, VanAcker said, including not just reptiles, but birds like the trogon and mammals like the coati. They’re among the nation’s most biodiverse mountains, and he said he hopes park designation will help keep them that way.

“Places like this should be preserved,” he said.

Brandon Loomis covers environmental and climate issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com. Reach him at brandon.loomis@arizonarepublic.com or follow on Twitter @brandonloomis.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

You can support environmental journalism in Arizona by subscribing to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona politicians seek state's fourth national park at Chiricahua