Hidden from the Nazis as a baby, this child of the Holocaust found a home in Fort Worth

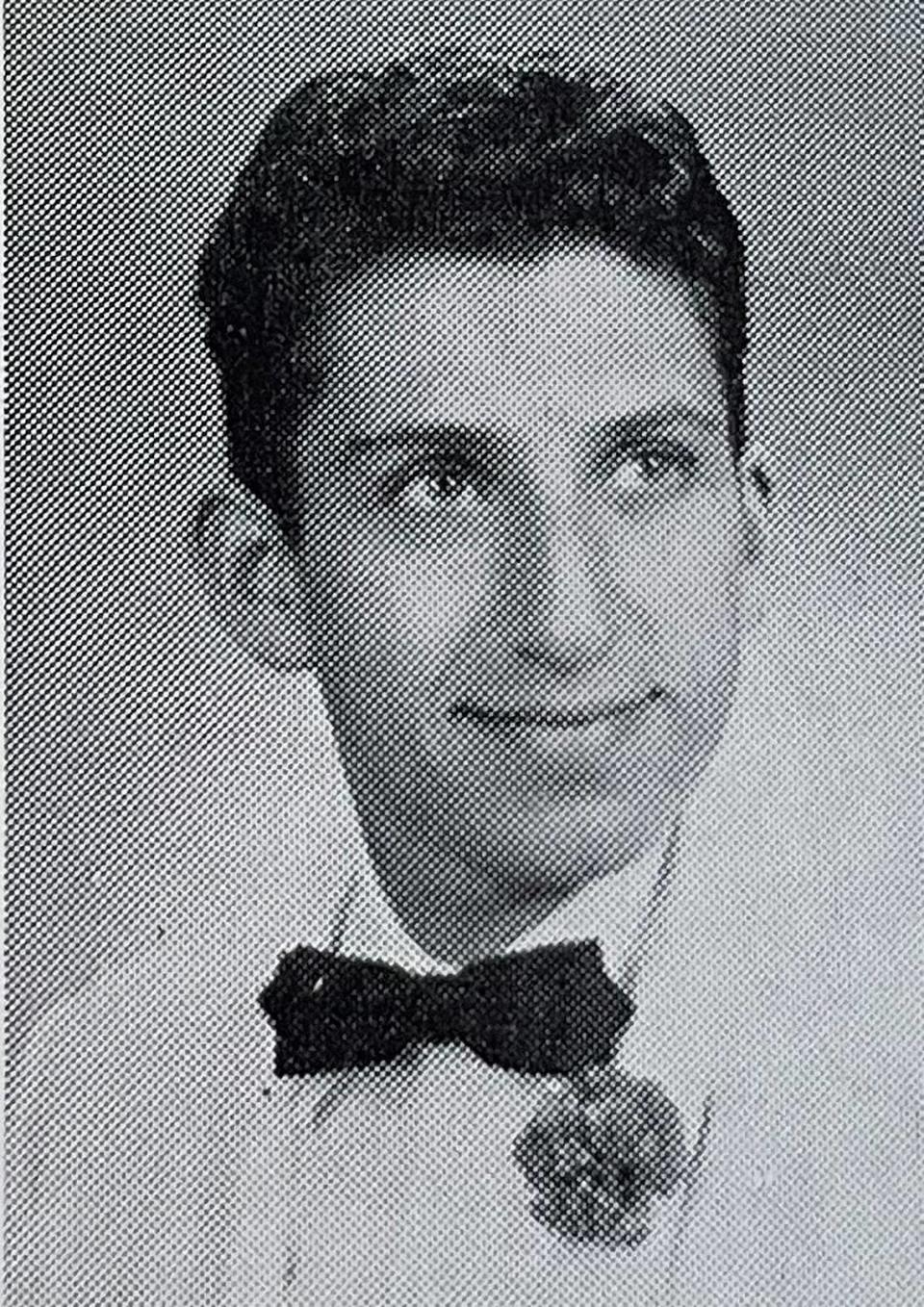

Harry Pila, an athletic teenager, spoke fluent French, Flemish, and Yiddish, plus a smattering of Polish. But Harry barely knew a word of English when his immigrant parents, Holocaust survivors with concentration-camp numbers tattooed on their arms, enrolled him at Rosemont Junior High in 1954.

To his embarrassment, 13-year-old Harry was held back, placed in seventh grade with younger students. They laughed at his accent, especially his use of a French word for “seal,” which sounded like a curse word.

Rosemont’s football coach needed a kicker. Certain that a boy raised in Western Europe could play soccer, he recruited Harry as the varsity team’s kicker. The lad was soon “living the dream as a kicking specialist at a football-obsessed ... school.” Within two months, he spoke English fluently and became a popular student.

The next school year, because his family had bought a house on Trail Lake Drive, Harry enrolled at McLean Junior High, where he skipped eighth grade. Finally, he was in classes with his peers — age-wise and culturally, for he already knew lots of McLean kids who attended his synagogue, Congregation Ahavath Sholom at Eighth Avenue and Myrtle.

“Harry adapted more easily than kids who had moved to Texas from New York,” recalled boyhood friend Arnold Gachman, who leads a century-old Fort Worth metal recycling enterprise founded by his immigrant grandfather. “Harry had a sense of humor. He was a personable guy. We played a modest game of poker.”

Harry knew how to roll with the punches.

In his recently published memoir, “The Journey of a Hidden Child,” part of Amsterdam Publishers’ series “Jewish Children in the Holocaust,” Harry Pila, now 82, candidly describes the twists and turns of his boyhood. With co-author Robin Black, he meticulously researches the “war-time footprints” of his birth father, who perished weeks before the Nazi surrender; the traumas of his mother Rose, who was painfully sterilized during medical experiments at Auschwitz; and the fortitude of his stepfather, Max Pila, whom he adored.

Born March 15, 1941, to Jewish parents in Nazi-occupied Belgium, Harry’s arrival was fortuitous yet “ill-timed.” The Germans were tightening “the noose,” formulating plans to exterminate Belgium’s 56,000 Jews. His parents’ best friends, a Catholic couple, agreed to raise the infant when he was 6 weeks old. Concerned that the birth of a baby to a woman who had not looked pregnant would arouse suspicion, his wartime “Maman and Papa” decided to raise the infant “in plain sight.”

They dressed the child like a girl, with frilly skirts and long hair adorned with ribbons. They did not change the child’s name. Rather they addressed the toddler with “terms of endearment” akin to honey and darling. This way, although their child was circumcised, it was doubtful the Nazis would pull down a little girl’s panties to verify religious identification.

Meanwhile, Harry’s biological mother Rose survived half a dozen death camps and miles of death marches in the snow. She returned to Brussels in 1945 when her son was 4. “With love and sensitivity,” she and the boy’s wartime parents transitioned him from one household to the other.

Harry remembers going to lunch with his birth mother at the Socialist Bund when Max Pila, a waiter who recognized Rose from before the war, flirted with her and brought extra desserts to their table. “Max was a great deal of fun, and I liked him immensely,” he writes.

“Shared grief drew Rose and Max together. Old social rules and norms went out the window. In less than three months, Max moved into our apartment, much to my delight.”

When the couple married in 1948, Max adopted 7-year-old Harry.

Max received vocational training to design and stitch ladies’ leather purses and shoes. With this skilled occupation, he traveled to the United States in 1952 and moved in with Rose’s half-brother in Brooklyn. Max “hated New York,” especially Brooklyn where streets were “packed with people” and piled with garbage.

One week, Max attended a Manhattan trade show. There he met Nathan Rakoover, the factory owner of Texas Sandal Manufacturing Co. on Fort Worth’s Northside. Rakoover offered Max a job making moccasins. The job came with transportation to Texas for him and his family, courtesy of the Jewish Federation of Fort Worth.

Cowtown suited Max. “It was just a little town,” he used to say. “ If you looked on the map, you couldn’t find it. ... It was a very quiet, clean, and the pace of life in Texas wasn’t too rushed.” In the fall of 1954, Harry and Rose joined him from Belgium.

“Our arrival was big news ... many people came and brought us food, clothes, and other items.” In time, Rose became the caterer at Ahavath Sholom. Max assisted her and became the shamas, which rhymes with promise and means the caretaker or sexton of a synagogue.

Among Harry’s lifelong friends are Harry Bailin, a fellow student in Paschal High’s Class of ’59. Bailin remembers visiting Harry’s home on Trail Lake and watching his parents sew beaded moccasins, trendy footwear in the 1950s. Coincidentally, Bailin spent his professional career in the shoe business.

Harry was accepted at Rice and Tulane universities but chose to attend the University of Texas, where in-state tuition was affordable at $50 per semester. He graduated in 1966 with a degree in international business and began climbing the global ladder in the import-export field. He and his spouse Susan, who have two children and four grandchildren, lived and worked in Fort Worth, Europe and Asia. These days they have homes in Boca Raton, Florida, and Florham Park, New Jersey.

The hidden child concludes his memoir on a triumphant note: “Hitler and his henchmen tried to kill us all. But we have the last laugh, as we are thriving.”

Hollace Ava Weiner, an author and archivist, is director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives.