High grad rates, flat test scores: Is an ambitious overhaul of Kansas schools working?

Santa Fe Trail Middle School in Olathe was among the first to undergo an overhaul of Kansas’ public school system, creating seismic shifts in how students are taught and prepared for life after graduation.

Now, a few years later, students are job shadowing and taking courses where they solve real-world engineering and environmental problems. They have more access to counselors and lessons on social-emotional skills.

On “Exploration Days,” they are immersed in experiences and classes outside of the regular curriculum. And they are required to spend time volunteering or serving the community.

Other educators are noticing. On Wednesday, administrators from the Hutchinson school district visited the school to learn from Principal JJ Libal, who has helped lead the redesign under Kansans Can — an initiative launched by the Kansas State Department of Education to rethink what makes a student successful and prepared for postsecondary education or the workforce.

It meant Libal had to work with the district to secure resources, move around staff and create a class schedule completely different than other middle schools.

“Boy, did we learn a lot. It was a great experience. Personally, I love the fact that we can innovate in a school and do something different. But it is stressful and challenging,” Libal told the Hutchinson administrators about the redesign process.

Five years into the program, Kansans Can is transforming education across the state. The Board of Education and Kansas’s top education official, Commissioner of Education Randy Watson, have led a broad shift toward less emphasis on assessment scores and more on “soft skills” that are difficult to define but essential for modern life, like good citizenship and work ethic.

The change is part of a national movement to reduce the importance of standardized testing and encourage a more holistic view of what student success should look like. Kansas has been one of the most aggressive states in re-orienting schools around this new approach, education experts say.

Watson and the Board of Education have made Kansans Can their signature initiative, and they are under pressure from parents and legislators to show results. The changes schools make now could affect students for years to come if Kansas sticks to the program.

But key metrics of student achievement paint a mixed picture.

The proportion of students in the lowest-performing categories for math and English on state assessments has grown over the last five years. In science, the percentage of low-performers rose over three years.

The average statewide ACT score has also fallen, from 21.9 in 2015 to 20.4 in 2020, though educators attribute that to more students taking the test.

On the other hand, dropout rates are falling. Graduation rates are improving, including for students from low-income families, students learning English as a second language and those with disabilities. More students are seeking education after high school.

“We always try to emphasize test scores are important but it’s an incomplete picture,” said Mark Tallman, a longtime lobbyist for the Kansas Association of School Boards. “And our ultimate measure, we think, should be how many kids graduate because that’s kind of the gateway to post-secondary ... that’s really the gateway to jobs, employment, earnings.”

Declining measures are not what legislators had in mind, however, when they channeled hundreds of millions to schools over the past few years. The funding followed repeated state court rulings that Kansas hadn’t constitutionally funded its schools after the state bailed on previous commitments to boost education budgets more than a decade ago. The Legislature approved more funding, but Republicans have demanded more accountability — and in some cases, control — over how dollars are spent.

Some teachers also worry about finding enough time to develop soft skills in students while improving, or at least holding steady, academic achievement. The new approach was already demanding, and then the pandemic upended school life.

Its full effect on academic achievement isn’t yet clear, but educators have already warned that they expect a drop in performance. Higher education officials are bracing for students who will struggle with learning loss.

Watson and other top education leaders say Kansans Can is helping, even if it remains a work in progress. Watson and Deputy Commissioner Brad Neuenswander recently completed a weeks-long tour of the state called the Kansans Can Success Tour where they described the initiative in warm terms while soliciting feedback.

At three tour stops attended by The Star, Watson and Neuenswander, while acknowledging problems caused by COVID-19, painted the brightest possible overall picture. They spoke at length about how the state’s current 88% graduation rate is the highest in state history.

They largely steered clear of falling and flat assessment scores. In an interview with The Star, Watson didn’t have a firm explanation for the data.

“I think we all can speculate,” Watson said. “And I don’t want to get into that too much because the true answer is we don’t scientifically know.”

A vision for overhauling education

The Kansas State Board of Education hired Watson, the superintendent of McPherson USD 418, as commissioner in 2015. He soon set out on a statewide listening tour.

Neuenswander, who joined the road trip, would later recount hearing at stop after stop that the accountability system for schools was “out of balance” with the priorities of residents.

“Kansans can say they value all of the things that help a young individual become successful later in life, but if we only measure the success of a child or institution based on a standardized test score, then we will most likely ignore examining the rest of the important components of a successful educational system,” Neuenswander wrote in a 2018 dissertation for a doctoral degree at Kansas State University.

While Watson and Neuenswander have emphasized the role public opinion played in the development of Kansans Can, they were also influenced by research underscoring the importance of schools teaching non-academic skills.

In his dissertation, Neuenswander cited a 2005 study by Harvard University, the Carnegie Foundation and the Stanford Research Center that found 85% of job success was dependent on employees having well-developed “soft skills and people skills.” He referenced Hart Research Association interviews with employers that found interest in effective communication, critical thinking and analysis.

A 2006 report by several business groups suggested that “despite their foundational importance, skills like reading and mathematics are not of primary concern to today’s employers,” he wrote.

What emerged from the tour was Kansans Can, a vision for education focused on preparing students for life after high school. To be successful in postsecondary education or the workforce, a high school graduate needs not only “academic preparation” but also technical and “employability skills”

The Kansans Can School Redesign Project followed. Under the program, districts applied to redesign individual schools around the Kansans Can vision.

To underscore the image of a bold, trailblazing venture, the project was branded after NASA’s space program, with each successive wave of districts named after chapters in the nation’s race to the moon: Mercury, Gemini I, Gemini II, Apollo I, Apollo II, etc.

In total, 71 districts out of more than 300 are participating, including some of the largest and smallest across the state. The largest district — Wichita USD 259 — has redesigned an elementary school and an alternative high school. Liberal USD 480, in southwest Kansas, appears to be redesigning more schools than any other district: five elementary schools, two middle schools and a high school.

“When the state board said we want to lead the world, they were likening it to when President Kennedy said we’re going to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade,” Neuenswander said at a Success Tour event.

While only a fraction of districts are formally participating in the redesign, educators at all levels say the concepts and philosophy of Kansans Can have spurred change across the vast majority of schools. In part, that’s because KSDE’s school accreditation system has incorporated elements of the Kansans Can vision.

“I visited a lot of school districts. I haven’t been to one that is not doing something directly related to those things,” said Jim Porter, who chairs the Kansas State Board of Education.

Hesston USD 460 Superintendent Ben Proctor said that while his district didn’t apply, educators have spoken over the past few years about how the district’s vision aligns with Kansans Can. It has built a “framework” that contains many of the same principles, he said. For example, Hesston uses individual plans of study for students, mirroring one of the core components of redesign.

Still, the district isn’t using some of the learning platforms, such as Summit Learning, that some redesign schools have deployed. Summit is an online site that allows schools to offer personalized lessons, in theory enabling students to learn at their own pace. It’s supposed to be a way for educators to provide the individual plans of study that are key to Kansans Can.

Parents and students in some districts with Summit have criticized the program, however, saying it forces children to spend too much time with screens. In 2019, about 50 middle school students in McPherson walked out of class to protest the program.

“There’s some separation, but I think you would find a lot of those core tenets of redesign in our vision as well,” Proctor said.

The Kansas City, Kansas, school district was not among the 80 that first joined the redesign. That hasn’t stopped Wyandotte High School teacher Sheyvette Dinkens from bringing many of the changes to her own classroom. Dinkens, a business teacher, has been moving away from traditional academic standards for the past few years.

She said students in her class are not required to take tests. Instead, she challenges them to come up with solutions on their own, to become critical thinkers and problem solvers. And she personalizes assignments depending on students’ skills and needs.

“Some kids cannot write that well and it stresses them out. So I let them video record assignments with their answers. And they love it. Sometimes kids want to work in groups, and sometimes they don’t,” she said. “The kids drive their own education.”

Dinkens believes that the statewide shift in Kansas’ educational structure is inevitable and necessary.

Across the country, educators are rethinking their reliance on test scores. Some colleges and universities have dropped standardized testing as an admission requirement. Last year, the University of Missouri-Kansas City, announced it would stop requiring ACT and SAT scores for admission. And last month, the University of Kansas said it will no longer use standardized test scores for admission or merit-based scholarships.

Dinkens said her class aims to prepare students for the workforce. And she believes that social-emotional learning is an important step toward getting there.

That could include lessons on team building and developing relationships, improving self-awareness or teaching the importance of perseverance. Many schools are surveying students, to measure their progress in self-regulating emotions, or to make sure they feel comfortable going to a teacher or staff member if they need support.

It also means, Dinkens said, teaching students tools to help overcome challenges.

“We can give students tests and want them to perform, but if we’re not addressing barriers to their education, they’re never going to perform. And they face a lot of barriers, like homelessness, mental health and family employment loss,” she said. “They’re never going to reach their greatest potential unless we help provide solutions to their situations.”

The KCK district — with 53% of students Hispanic; 26% Black; and 81% considered economically disadvantaged, per state data — has different challenges than its rural, whiter counterparts. She also worries how such broad changes can be implemented when some teachers are instructing dozens of students, who all have different needs and are learning at different levels.

“The big question is with the teacher shortage, how do they plan to make this happen?” she said. “That’s the biggest hiccup now. Now that we have this great teacher shortage, how do we execute this plan?”

Mixed metrics

The Kansas shift follows larger national trends. The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, which required a focus on test score growth and academic progress, led to a backlash that led to its replacement in 2015 by the Every Student Succeeds Act.

The new law still requires standardized testing but hands states significantly more freedom in setting goals.

Jennifer DePaoli, a senior researcher at the Learning Policy Institute, a D.C.-based education policy think tank, said an understanding took hold after NCLB that schools needed broader metrics of what constitutes a successful student and a successful school.

“Kansas is one of the very few states that has taken on something of this magnitude at the state level and especially in the areas of personalized learning, building around relationship-centered schools and making sure students have that experiential learning,” DePaoli said.

But after five years, Kansans Can is having a gut check moment.

Watson grabbed headlines on the Success Tour promoting an 88.3% graduation rate — the best in state history. He also touted a what the department calls “postsecondary effectiveness,” which tracks the percentage of ninth graders who entered college or who earned a postsecondary degree or certification two years after high school.

According to KSDE, the 5-year rolling average for the effectiveness rate is 48%, up from 44% when Kansans Can began.

But questions about academic achievement are growing. Top lawmakers on Wednesday authorized a special education committee to meet this fall to study academic achievement, including KSDE’s priorities coming out of the Success Tour.

“From the Legislature’s point of view, I think achievement is our number one priority,” said Rep. Kristey Williams, an August Republican who chairs the House K-12 Education Budget Committee. “We want our kids, of course, to be healthy, secure — physically, mentally — but we also want high achievement standards.”

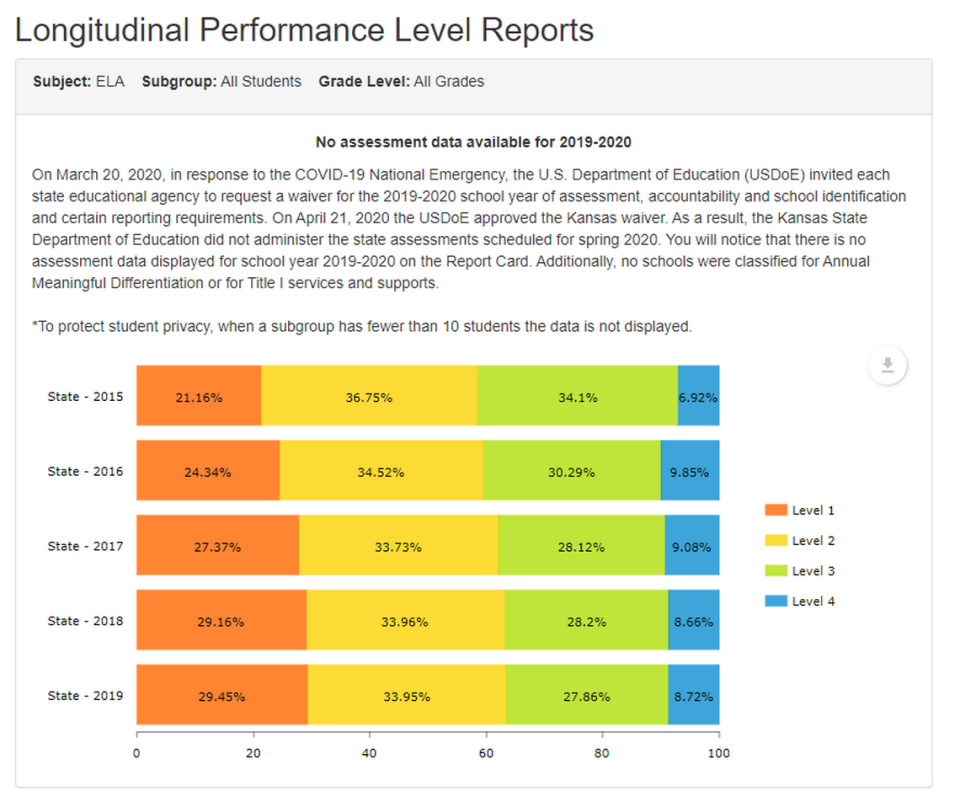

In 2015, 23% of students were in the lowest level of math performance measured by state assessments, according to data posted by KSDE. That number rose to 29% in 2018 before dipping slightly to 28% in 2019. Assessments weren’t conducted in 2020 because of the pandemic.

English is a similar story. About 21% of students were in the lowest-performing category in 2015, compared to more than 29% in 2019.

“That’s the challenging piece, right, because the community is still going to look at those test scores, the administration is still going to look at those test scores,” said Rep. Fred Patton, a Topeka Republican who was on the Seaman USD 345 school board for more than a decade before resigning earlier this year.

“Even if you say you’re not emphasizing them as much, everyone’s still going to look at those,” he said.

Watson predicted Kansas should begin to see rising academic scores, along with other areas of achievement.

“We should not come to accept that we’re going to have flat or inconsistent academic scores,” Watson said. “But what I think we can say is in Kansas, we don’t only just teach the test. We don’t just test prep. Especially when time is of the essence and we want to make sure that kids have other skills, too.”

While cautioning that educators truly don’t know the reason for flat scores, Watson suggested in the interview that while No Child Left Behind pushed schools to aggressively prepare students for tests in core areas and that many posted good scores, it came at the expense of other areas and subjects.

Education officials now look at more measures, he said.

“Dual enrollment is up. AP exam scores over the same period are up. Postsecondary is up. And our remedial rate is down,” Watson said. “Now that makes us look at those test scores and go, ‘why aren’t they moving also?’ And I don’t have an answer for that.”

One measure favored by KSDE is the graduation rate. As Watson noted on the tour, 88.3% of students are now graduating on time, up from 85.7% in 2015.

Students from low-income families, students with disabilities and students learning English are also improving. While they still graduate at a lower rate than the state as a whole, those categories of students have been improving more quickly than their peers and are closing the gap.

All three groups had graduation rates of less than 78% in 2015. In 2020, they had all broken 80%.

Williams questioned whether rising rates are indicative of lower standards, however. “If graduation rates are rising, my question is: are standards dropping?” she said.

For their part, Watson and others are actually cautioning that the rise in graduation rates is likely to slow. Many of the students who don’t graduate on time or at all face significant barriers.

“It’s just going to be very difficult to make significant progress quickly,” said Sen. Brenda Dietrich, a Topeka Republican and former superintendent of Auburn-Washburn USD 437.

The state Board of Education has set a statewide graduation goal of 95%, which would vault Kansas to the top of the nation. Dietrich and others warn it will be difficult to achieve.

“That doesn’t mean anybody has given up, it’s just the progress will be a little bit slower,” she said.

Hoping for a ‘rebound’

At Santa Fe Trail Middle School, academic achievement remains one of three areas of focus, along with social and emotional support, and civic engagement.

The school has created a new course, called project-based learning, for students to explore their interests and tackle societal or industry problems. In classes, Principal Libal said, some students have learned how to design flexible schools with modern technology. Others advocated for the district to equip schools with refillable water bottle stations.

The goal is to get students thinking outside of the classroom, and to see the connection between lessons learned and future careers.

The efforts have been hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic. This school year, only 8th graders will participate in project-based learning. It was previously available at all grade levels.

The pandemic upended the final part of the 2019-2020 academic year, when Gov. Laura Kelly became the first governor in the country to order schools fully remote for the remainder of the semester. Many districts juggled in-person and remote learning the following year.

Now in the third academic year of the pandemic, districts are under a new state law restricting remote instruction. Amid the delta variant, buildings are again struggling with quarantines of large numbers of exposed students. Some districts have even suspended classes for periods of time.

Research shows that students lost months of learning last year, as they shifted from online to in-person classes. Kansas Board of Regents President Blake Flanders said Wednesday that universities are preparing for students in the future who will have learning loss.

Watson said the trauma of the pandemic is still present and he is bracing for a decline in academic performance. He said educators have already seen a drop in attendance and post-secondary enrollment, especially in trade schools where students were resistant to virtual learning.

“We hope that rebounds back,” Watson said.

Libal’s not willing to fully turn the focus away from traditional academic achievement standards.

He said he felt it was important to ensure that sixth and seventh graders have additional time and support this year to catch up in reading. During the redesign, the school has set aside more time for “academic intervention,” where teachers work one-on-one with students to reteach and remediate with students who need it.

“We really want to focus on what our kids need. And when we have students who are not at grade level, project-based learning is great and we love that, but we also need to make sure our students are achieving and doing well,” he said. “So we try to incorporate both.”