High-quality child care is too expensive. Government subsidies are too low to help.

This story about child care subsidies was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — Layoni Haskins, 3, had been asleep in the back seat of her mom’s car for almost an hour. In the strengthening morning light, Imari Haskins checked her youngest daughter’s sleeping form in the rearview mirror and decided to let the girl rest a while longer.

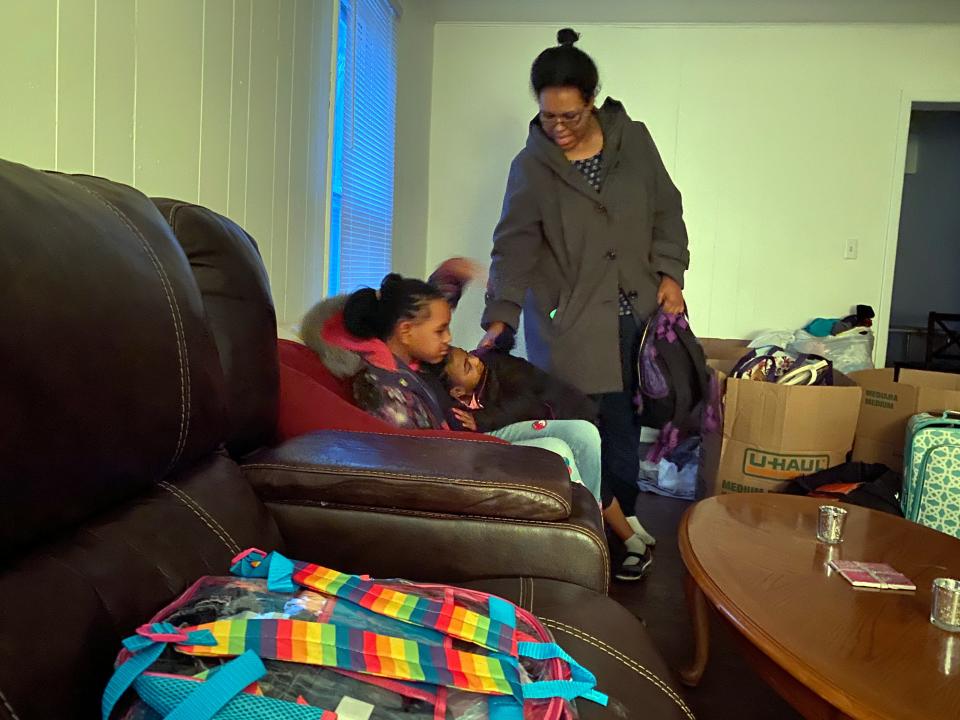

It was 8:38 a.m. on a February morning and Haskins, 32, had pulled up in front of the duplex where she lives with Layoni and Jaslynn, 9. The family had just moved and had to wake up earlier to make the half-hour drive across town to Jaslynn’s elementary school, which is in their old neighborhood. This morning was especially rough because no one had fallen asleep until after 1 a.m. the night before.

Haskins, a single mom, works around 70 hours a week as a certified nursing assistant at a local elder care facility. She picks up as much overtime as she can, which often means working pretty late. Last night, it was 11:30 p.m. before she was able to pick up her sleeping girls from the woman who watches Layoni full-time and takes Jaslynn after school. By the time they’d woken up, climbed in their mom’s car and driven across town, both girls were “wired” and it took them a long time to settle down.

To find child care she could afford and that would accommodate her unpredictable work schedule, Haskins ended up with an unlicensed provider who charges about $600 a month. That’s nearly a quarter of the $31,000 she earns in annual take-home pay, but still less than the price for most licensed care in Michigan. Like the majority of parents in her income bracket, Haskins gets no government help covering that cost.

In fact, the federal government provided child care subsidies to just 1 in 6 children eligible to receive them in 2015, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The vouchers that are provided are rarely sufficient for parents to cover the cost of high-quality care. And the eligibility guidelines are so tight that millions of families who could benefit from assistance get nothing. Ultimately, by offering the poorest families insufficient assistance to access excellent child care and by denying help to millions more low-income families, the federal government is effectively lowering the quality of child care available to a huge segment of the American public.

Parents want affordable child care: Why can't they get it?

With tens of millions of Americans now out of work and more than half of child care facilities at risk of closing for good, the instability and insufficiency our child care “system” has been laid bare. Even as many centers re-open this summer, concerns about sustainability persist. With current federal funding running dry and many states calling for smaller class sizes to lessen the chance of a large coronavirus outbreak, child care centers stand to lose crucial revenue that could force closures even among businesses that survived the initial crisis. And while the pandemic is unprecedented, the problems faced by child care providers are not new.

Not enough money to 'ensure quality care'

A Hechinger Report review of hundreds of pages of child care inspection and incident reports from three states over the past year found frequent staffing issues, routinely inadequate facilities and too little attention paid to health and safety. Although many of the child care options available to parents on a tight budget were able to provide a generally safe environment, the problems we discovered reveal how lower-income families are forced to gamble with their children’s well-being.

“Child care is not funded to serve all children who are eligible, and it’s not funded to provide rates that ensure quality care for all eligible children,” said Karen Schulman, the child care and early learning research director at the National Women’s Law Center, which advocates for gender equity.

Haskins used to benefit from a child care subsidy program, commonly referred to by parents and providers here as DHS, shorthand for Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services. Like child care assistance programs in every state, more than half its funding comes from the federal government.

When she was earning her nursing assistant certification, Haskins had fully subsidized care.

“Once I started working, DHS started cutting me off a little bit at a time,” she said. “They started off doing 100% and then it went down, then down again. I had to keep paying more and more. It got too expensive for me.”

The primary federal source for child care subsidies is a $5.83 billion program known as CCDBG, or the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Federal coronavirus aid through the CARES Act added $3.5 billion to that fund, an amount advocates say is far too little to meet this year's need. The annual amount in the program has grown very slowly over the past two decades, barely keeping up with inflation and serving fewer families now, in real numbers, than it did in 2000.

“If you look at where we are and where we need to go in terms of the families who need help, we are not talking about small, incremental increases,” said Hannah Matthews, the deputy executive director for policy at the Center for Law and Social Policy, a nonpartisan organization focused on policies that help low-income people. “This is a major investment that the country should make in terms of supporting early childhood and access to child care.”

All told, 1.3 million children, about two-thirds of whom are 6 or younger, enrolled in child care with the help of federal subsidies in fiscal year 2018. About 11 million more were eligible to receive the money, but didn’t, according to the latest numbers from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Many states do not even keep track of who is eligible and can’t be served, Matthews said.

“In some states, waiting lists have tens of thousands of families on them,” she said, while others “simply close enrollment, effectively turning away eligible families.”

It is even more difficult to estimate the number of families who don’t qualify for government subsidies, but who make so little that assistance covering child care costs would make a big difference to them. Families who earn more than poverty-level wages but still live on a subsistence budget account for about 33 million American households, according to Laura Bruno, a spokesperson for United for ALICE, a research and advocacy organization focused on America’s working poor. United for ALICE doesn’t have data for how many of these families have children or how many qualify for aid.

Child care subsidies fall short for a simple reason: Congress doesn’t determine how much money it allocates based on the number of families in need or on how much good child care costs.

This is mostly because when the child care money was first approved in 1990, it was not imagined as an entitlement for everyone who needed it but rather as a tool to get low-income women to work, said Schulman from the left-leaning National Women’s Law Center. The law was set up this way for two main reasons, according to a report by the center: prejudice against the mostly black and brown mothers who needed subsidized care and a devaluation of the work of caring for children, which was (and is) considered a woman’s natural role. The lack of female representation in Congress at the time — of the 535 people in Congress in 1990, only 31 were women — likely didn’t help.

What is systemic racism? Here's what it means and how you can help dismantle it

What subsidized child care looks like

To discover what it is like to run a business on the amounts that are offered to providers, reporters from The Hechinger Report knocked on the doors of more than a dozen home-based day cares in western and northern Michigan. All of them had received at least one citation for violating regulations. Many of the homes were empty when we arrived, but about half of the providers we sought were available and willing to speak with us.

Wendy Tilma, 42, came to her door with three big friendly dogs at her heels and a handful of kids tagging along behind them. Tilma is a home-based provider in Byron Center, a small town south of Grand Rapids. She was happy to talk and invited us to spend a day at her home day care in early March, before coronavirus nearly shut her down.

Tilma said she lives comfortably but only because she works enough extra hours to care for 15 kids on a staggered schedule, instead of the maximum of 12 she can have in the house at one time. Four of those 15 children are covered by state subsidies.

“I’m losing money every month” on the subsidies, she said back before coronavirus became everyone’s primary concern.

Her day care was already on the brink: Then coronavirus struck.

Tilma earns nearly $200 more per month from each family that pays her directly than she does from each family that receives child care subsidies. She’s allowed to ask families on subsidies to make up the difference but doesn’t because, she said, “they’re on state assistance for a reason.”

She lost the majority of her business in late March due to coronavirus. But by late May she was back up to seven kids on her roster and was waiting to hear about a state grant that would help her cover the cost of her lost enrollment.

Neither Tilma, nor Haskins, nor any of the other providers or parents interviewed for this story mentioned the federal government when sharing their gripes about subsidy amounts. Their ire was reserved for the state, which they saw as the primary source of subsidy money. And while Michigan has made several choices that make it a difficult state for those who rely on subsidies, it is ultimately constrained by what the feds offer, according to Schulman.

“States are making choices, but it’s not real flexibility because they’re weighing trade-offs,” said Schulman.

States must spend their own money to qualify for the federal grants. How that amount is calculated is complex. Essentially, a formula determines the sum each state must pledge to child care spending to get the full amount of child care assistance offered by the feds. Partly for this reason, exactly how much subsidies are worth varies greatly from state to state. In 2019, only four states were offering the recommended amount.

“It’s not up to reflecting the market,” Schulman said of the child care block grant. “And the market doesn’t reflect what’s needed to provide the necessary wages.”

Child care workers, who earn an average of $24,230 a year, often live near the poverty level themselves. Just over half are eligible for some form of government benefit. The stress caused by these tight circumstances can also affect the quality of care they provide.

When the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act was last reauthorized in 2014, it came with new rules requiring states to uphold certain quality standards in order to get federal money. Those standards are still fairly weak. For example, states must have age-based rules about how many children can be watched by a single adult. But the federal law does not mandate what those ratios should be. Also, Congress did not provide the money to make the required quality improvements until 2018 when it approved an additional $2.4 billion for the Child Care and Development Fund, the single largest increase in the fund’s history.

Given how little money is actually passed on to providers, though, many find the quality standards difficult to meet.

'She'd shut me down'

Despite requesting data from three different state agencies in Michigan on which providers receive subsidies, we were unable to find an answer. None of the agencies we contacted were able to provide the information we asked for or correctly direct us to an agency that tracked it. However, public records of violations examined by The Hechinger Report reveal that among licensed child care providers in Michigan, many routinely face problems because of their shoestring budgets.

Enrolling too many children was especially common. One provider’s husband ran out the back door with a kid (to visit the local park) when an inspector arrived. In a text to the parent who had contacted the state child care licensing division, the provider wrote, “I live week to week. ... I can’t afford to not have as many kids as I’m allowed to. [My husband] works at salvation army [sic]. If I miss one person I can’t pay the bills.” In a follow-up text referring to the state inspector she wrote: “I’m over kids and she’d shut me right down.”

Another provider, in a more urban area, was also investigated for watching too many kids by herself, which she explained she had done because her assistant did not have her own transportation and was late in arriving. Similar issues with employees unable to keep reliable schedules were noted in several of the records examined by The Hechinger Report.

Tilma has been cited for a number of violations over the years, including peeling paint on her front door in 2006, not keeping accurate attendance records in 2011 and letting her now ex-husband supervise kids while she took a child to a dance class in 2017. Tilma saw these violations as irrelevant to her ability to care for children in a safe and loving way.

She’s also been cited multiple times by state inspectors for being over capacity or for having too many kids for each adult. She thinks her experience — nearly 20 years running a home-based day care — should earn her the right to care for more children.

“I’m always playing the numbers game,” she said. If the state paid better, she said, “then we wouldn’t need as many kids to take care of to make ends meet.”

Like Tilma, many of the child care providers cited in the inspection reports examined by Hechinger were home-based. These providers tend to have less formal education, according to the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley. And though exact data is hard to collect, home-based providers also generally earn less than those who work as centers, said Marcy Whitebook, director emerita of the center. Children who attend home-based care also lag behind in reading and math skills by the time they start kindergarten compared with their peers who attend high-quality center-based care.

Yet home-based providers account for the majority of licensed providers in more than 20 states, according to Child Care Aware. And many families prefer the home-based model.

“Home care is more loving, more hands on,” Tilma said.

On a chilly day in early March, Tilma was watching five children in the living room of her modest ranch home. She opened the day with circle time, teaching the kids their numbers, letters, shapes and colors. She didn’t raise her voice all morning. When she told a child who was not following the rules that it would soon be time to “take five,” the girl changed her behavior. Tilma made chicken quesadillas for lunch, with canned carrots and pears on the side. The kids cleared their own dishes after eating and put toys away when asked. They knew the routine.

But Tilma didn’t change either of the toddlers’ diapers between nine and noon and her outdoor space was unusable that day because there was too much dog poop in the play area. Recently, she said, she got in trouble for not turning in her paperwork on time.

“They’re not going to take my license away,” she said. “There are not enough good providers.” And even if the state did revoke her license, she added, “these kids will still show up to my house.”

'They won't help you'

Nationally, state regulations set a low bar for quality. Nearly anyone can qualify as a child care provider in the majority of states. As of 2018, 41 states had no minimum education requirements for home-based providers, according to an analysis by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. At the same time, many rules that do exist can seem illogical or overly burdensome. A rule that calls for changing diapers only in the bathroom, for example, could also mean leaving some children unattended. (Day care centers are generally designed with no-door bathrooms to accommodate this common rule.)

Like most states, Michigan does some things well and other things poorly. In 2018, the state served about 40,000 children, a typical amount for a state of its size. It is one of just a handful of states that has historically failed to spend the amount the federal government has deemed necessary for it to qualify for its full federal grant. As a result, money originally earmarked for Michigan has been redistributed to other states. And yet, like 42 other states and territories, Michigan used the recent increase in Child Care and Development Fund money to serve more families and boost its payments to providers. Michigan also joined 28 other states and Guam in increasing the number of children served.

Michigan also has a relatively low cut-off for who gets subsidies. All states offer subsidies to families at or below the federal poverty level ($21,720 a year for a family of three), but only 15 continued to offer assistance to families at or above 200% of that level, even though that is considered the bar for self-sufficiency by economists. Haskins is somewhere in between but, as a Michigander, she is cut off from financial aid for child care once she earns more than $26,556, or about 125% of the federal poverty level for a family of three in 2019.

“If you’re working and making a certain amount, they won’t help you,” Haskins said. “So you’re stuck.”

In some other states, Haskins would get at least some child care assistance, though she’d likely still be required to provide a co-pay. (In 26 states, co-pays for families at 150% of the federal poverty level end up costing more than the 7% of family income considered an affordable amount to pay for child care, according to a state policy report by the National Women’s Law Center.)

Haskins considers herself middle class, but there is nothing comfortable about her budget. Out of the approximately $2,600 a month she takes home each month, $995 goes to rent, $600 goes to child care, $400 covers her car payment and another $150 to $200 goes to utilities and gas for her 2016 Jeep Patriot. That leaves about $400 a month for food for three people and anything else that might come up. She pays for karate for Jaslynn. She’d like to add basketball but isn’t sure she can. She gets most of the girls’ clothing secondhand and she counts on the free breakfast and lunch Jaslynn gets at school to make things work.

Haskins has looked into center-based care, which she thinks might be higher quality and better run — on average, that’s true — but most centers can’t accommodate her work hours, and they cost more than she can afford.

“The way things are going in terms of how expensive they’re getting, you can’t afford to pay for child care and pay to live,” Haskins said.

Meanwhile, problems abound with the way the subsidy money is distributed to families. Some states are less likely to give subsidies to parents pursuing an education instead of working or looking for work. Others will give money to student parents but only to finish high school, not college, even though a college degree is more likely to lead to financial independence.

Many states stop paying providers if a subsidized child is absent for a certain number of days. In these states, if a child exceeds their number of allotted absences, the provider is not compensated, even though she’s reserving space for that child.

Parents who earn even a small raise at work can find themselves no longer eligible for benefits and suddenly unable to afford something they had covered when they were earning less, turning their raise into a pay cut. (Federal law now requires states to offer a gradual decrease in subsidies when family income increases, ideally eliminating the sudden transition to self-pay, but in many cases it only slows down the same process.)

And there can be seemingly nonsensical rules like one in Michigan that requires applicants to have both a job and a provider lined up before being approved for child care assistance. But few providers are willing to take a child whose parent may or may not be able to pay. And few employers paying $10 an hour or less are willing to make a job offer and then wait to fill the position while the applicant finds child care.

Ultimately, the American child care system has survived almost solely on the backs of low-income women, many of them women of color, who care about children enough to do their best despite very low wages. Ironically, their hard work has made their plight easier for society to ignore.

“Who needs and offers child care and how little we invest in it are not disconnected,” Schulman said.

A handful of elected officials in Washington have begun to recognize the problem.

“Access to high-quality child care and education during the early stages of a child’s life should not be a privilege reserved for the children of the rich,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren told a crowd last year at the annual gathering of the National Action Network, a civil rights organization founded by Rev. Al Sharpton.

Warren has proposed, both in Senate legislation and on the campaign trail for her failed presidential campaign, a universal child care system like those found in other developed nations. (So far, presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has said only that he would push to expand the child care tax credit to up to $8,000 for some families from a current max of $6,000.) Now, Warren, along with Minnesota Sen. Tina Smith and Washington Senator Patty Murray, both Democrats, and a growing coalition of advocates, is helping to lead the fight for more coronavirus relief funding for child care.

Parents ask: Who will care for kids as my job reopens?

At the end of May, another group of Democratic lawmakers introduced the Child Care Is Essential Act, which calls for $50 billion to stabilize the child care sector thought a grant program that would be open until September 2021. The money could go to providers regardless of the income level of the families they serve. The fate of this bill is unclear in a Congress that has quickly retrenched into partisan debates, though in recent weeks several Republican lawmakers have spoken out in favor of at least some additional federal support for child care.

But so far, despite the effects of the pandemic making the system’s weaknesses more apparent, despite growing attention from high-ranking politicians, despite broad public approval for spending more taxpayer money on child care, and despite bipartisan agreement that helping families afford care is a good idea, the money to make child care high quality and easily accessible in America has simply never materialized.

And since mid-March, the need for federal intervention to shore up our nation’s child care system has gone from pressing to dire.

Reporting contributed by Jackie Mader and Sarah Butrymowicz.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Daycare cost: Best child care centers too pricey for people on subsidy