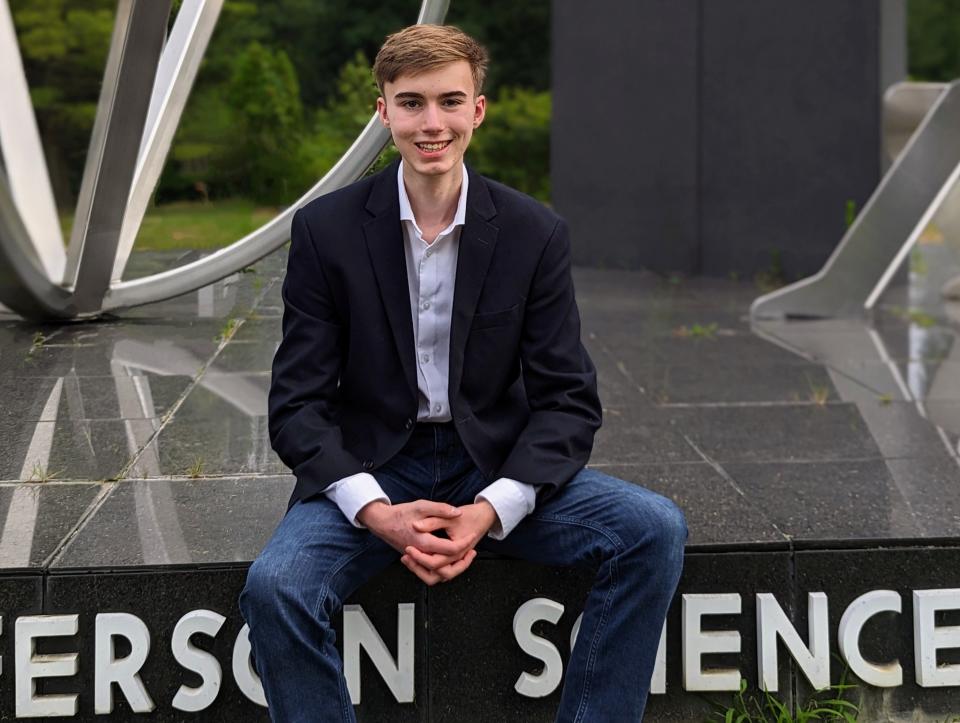

Can this high school student fix American politics?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

After emerging from his virtual pandemic year at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, Eli Tillemann was eager to meet people in person. He examined his club options: astronomy club, urban dance, Rubik’s Cube club.

But Tillemann, then 15, gravitated to politics and global issues and was looking to have conversations — to “discuss stuff,” he told me. He grew up with a Democratic father and a Republican mother, a combination that elicited vibrant debates in his household.

Perhaps that’s why it didn’t seem that strange for Tillemann to join both the Young Democrats and Teenage Republicans clubs at his school. And later, in his junior year, to run for president of both clubs — and win.

“This was very confusing to us,” Sarah Tillemann, Eli’s mother, told me, laughing. “Why don’t you just pick one?”

But for Eli, it was important to be exposed to a variety of perspectives at Thomas Jefferson, a top-rated public magnet high school in Alexandria, Virginia. And he found them in the clubs, meeting a self-proclaimed communist and students who were ideologically far right, among others. “Honestly, there was a lot of great discourse on both sides,” he said.

Now 17 and a rising senior at the helm of both Young Democrats and Teenage Republicans, he’s helping his peers get better at building consensus and disagreeing civilly and respectfully at a time when the whole nation could use this sort of lesson.

Could his example help lead the way?

A family tradition

To many Americans, the country’s biggest challenges feel abstract and insurmountable. But to Tillemann, issues such as climate change, the national debt, foreign aggression and bolstering democracy are concrete problems that we can do something about, even though they are often fraught with emotion.

“All of these things should be bipartisan issues. But these things are not bipartisan issues, and we’re just fighting over them,” he tells me on a Zoom call. “And that’s what I’m trying to change.”

Tillemann’s proclivity for activism was known to his parents from a young age. In second grade, he started his own civil society, polling the neighbors about the cause they cared about most. He started two newspapers, one of them a family paper he launched during COVID-19, recruiting siblings and cousins as writers.

Growing up on Capitol Hill, the firstborn son of two congressional staffers, he often accompanied his parents to events where they mingled with foreign dignitaries and politicians. Tillemann was a few months old when Sarah pushed him in a stroller to a North Korea human rights rally. As a toddler, Tillemann stole a muffin from the chair of United Nations Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon.

Sarah worked for Henry Hyde, a Republican representative from Illinois, and worked on the House International Relations Committee, covering East Asia affairs. (She also served a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Hong Kong.) Tillemann’s father, Tomicah Tillemann, worked for the then-little-known Democratic senator Joe Biden. He was also a policy advisor on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and then Hillary Clinton’s speech writer.

Sarah and Tomicah met as graduate students at the School for Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins while eating lunch in front of a giant piece of the Berlin Wall displayed in the courtyard. Both Latter-day Saints, they got married two weeks after graduation and went on to have five children.

In his parents’ conversations about the Arab Spring and tumult in the Middle East and North Africa, Eli recalls that Sarah and Tomicah weren’t always on the same page. “I definitely got to hear both sides of the spectrum,” he told me. “But what surprised me so often is that they agreed on so much.”

Early in their courtship, Sarah gave Tomicah a copy of Norman Rockwell’s illustration “The Debate,” which ran on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in October 1920. In the sketch, a woman and a man are seated back to back, holding newspapers, their faces unhappy. The illustration hung in the family’s home in Falls Church, Virginia, for years, until one of the kids accidentally knocked it off the wall.

The legacy of Tillemann’s paternal grandfather, Tom Lantos — a Hungarian Holocaust survivor and influential human rights advocate who served in the U.S. Congress — broadened the aperture on differences along party lines in the family and instilled in Tillemann a commitment to justice. “Eli’s grown up in a world where human rights is a big part of our family story,” Sarah said.

Steeped in this environment, Tillemann perceived early on that government was more accessible than it appeared. “The system can be changed through advocacy, through reaching out. There is a lot of impact that we can have,” he told me over Zoom, his face flushed with enthusiasm and resolve.

Tillemann speaks in a measured and deliberate manner, divulging opinions ranging from concerns about Defense Department spending and China’s relationship with Taiwan to the ongoing war in Ukraine. He compliments me on my questions before launching into responses that feel like he’s just been waiting to share.

American politics are kind of sad now, he tells me. The headlines these days, he says, accentuate the polarities: doomsday legislation passed by one side; some politician on the other side who is “destroying” America.

“Americans will read that, will believe that, and Americans will vote as a result of that headline,” he tells me. “We’re getting pushed further and further apart into these camps with some moderates left straggling behind in the middle.”

Equity and excellence

Tillemann’s school community has been embroiled in a controversy that began unfolding during his freshman year at Thomas Jefferson — or “TJ,” as it’s known in Fairfax County.

With the goal of expanding the number of Black and Hispanic students, the school canceled the standardized test and teacher recommendations, reserving seats for students from across the area’s middle schools, some of which serve lower-income communities. The decision sparked uproar from a parent-led group, which argued in a lawsuit that the policy discriminated against Asian American students, who made up more than 70% of the student body. Although a federal appeals court recently upheld the policy, the case is expected to come before the Supreme Court, which recently struck down affirmative action at colleges and universities.

Tensions ran high in the community in the aftermath of the changes, dividing students at the school, Tillemann tells me. Many students felt the policy wasn’t fair to them: they worked hard to get in. “But a lot of students also felt the new policy was important and wanted to see social change.”

Tillemann brought the issue to both the Teenage Republicans and Young Democrats clubs to openly talk about the controversy and what could be done.

“Will the administration listen to us? Probably not,” he told me. “But the exercise of debating the issue civilly has been very beneficial.”

Tillemann has been trying to make sense of the implications of the policy for himself. His brother, “a very gifted kid,” did not get into the school, and Tillemann suspects it’s partly because of the new geographical groupings. He believes a better solution lies somewhere in the middle. Instead of regional admittance caps, the school could help disadvantaged students by creating a separate low-income application bracket, he said.

“Debates around equity vs. excellence in education are increasingly polarized, and we shouldn’t have to choose between the two,” he wrote to me in an email.

Michael Miller, Tillemann’s English teacher this year, worked closely with his student on a research project Tillemann chose to do on the role of critical race theory in Virginia’s 2021 gubernatorial election. “When you speak to Eli, he’s bursting with ideas,” Miller said.

Invested ‘on a cellular level’

To help members of both of the Republican and Democrat clubs learn some hands-on strategies and even science behind civil discourse, Tillemann has enlisted the help of James Niels Rosenquist, an economist and practicing psychiatrist who teaches at Harvard Medical School, and Stuart Schulzke, an executive at a digital database of government documents. Years ago, Schulzke taught Hungarian to Tillemann’s father at the Latter-day Saint Missionary Training Center, in preparation for Tomicah’s mission in Budapest.

Close friends who often disagree, Rosenquist and Schulzke began thinking about what it is that can sustain a friendship knit tightly in spite of seemingly intractable differences. Their conversations led to starting Dialectic, a nonprofit that offers a framework and methodology for having more constructive and informed disagreements that are less dependent on emotion.

With the project, they set out to salvage civil discourse from catastrophic decline. “We’re trying to provide a set of mechanisms and best practices to prepare people to have emotionally fraught disagreements without letting emotion overcome the process of understanding where the other person is coming from,” Schulzke said. Without these skills, when people disagree vehemently, it’s a bit like sending Luke Skywalker to confront Darth Vader without any preparation, he added.

After filing a heap of paperwork with the school’s administration, Tillemann brought a series of in-person Dialectic discussions to joint meetings of his two clubs. The students talked about humans’ disposition for tribalism, the impact of social media on psychology and neuroscience behind it, and how to listen to opposing sides. The conversations have been non-partisan and “upstream” — less about a particular viewpoint on an issue, but about preparing the mind for scenarios when students have difficult conversations.

That’s a challenging thing to do, Rosenquist argues, partly because our minds are simply not prepared for “the unique cognitive challenges of the 21st century.”

“Our bodies are not adapted to a world in which we’re not communicating with each other the same way we evolved for millions of years to do,” Rosenquist said.

Learning to debate and disagree is like teaching basketball or martial arts to someone who is still mentally on the couch, he said. “If you don’t have the kind of mind training to prepare yourself for those kinds of conversations, you’ll invariably get sucked into this powerful emotional tug towards a tribal setting, which our ecosystem of Twitter and imperfect communication has led to,” Rosenquist said. “We are programmed to immediately get triggered into … intense emotions that overpower who we are.”

Teaching the dialectic framework to teens is particularly impactful while they are learning the modes of confrontation and forming their views of the world, Rosenquist says. They can use their cultural touch points to spread these ideas to other student populations, he adds. And Tillemann has been instrumental in that goal. “Eli is really invested in this on a cellular level in ways that go beyond things he’s doing for school,” Rosenquist said.

Work-life balance

Tomicah and Sarah continually remind Tillemann of the elusive work-life balance — telling him that he doesn’t need to take all the hardest classes and pursue every opportunity available; that solving big problems takes time. “His well-being is far more important than his achievements,” said Sarah.

At home, Eli builds Legos with his younger siblings and takes it easy on Sundays. “When he puts down his homework to do something with us, I’m like ‘oh, good’ — that’s called life balance,” Sarah says.

On the Friday that I spoke with Tillemann, he had just finished finals and the summer could now unfold in its fullness. In a few weeks, he would head to the San Juan Islands in Washington state to visit grandparents, hike and kayak, and take in views of the ocean.

Yet, there is a tinge of disappointment that comes through Tillemann’s voice that maybe he could have squeezed in more. He wishes he had time for an astronomy class. “I could probably have done more engineering or more biology classes,” he told me. “But right now, what I’m looking for is understanding.”