These high school students were afraid to dream bigger. A Stanford class is changing that

Jennifer Cisneros, a 10th-grader at Birmingham Community Charter High School with a 4.2 GPA, said she “never really thought about” applying right away to her dream universities, USC and UCLA. She planned to go to community college first because she felt it would be easier to adjust to the rigors of college courses.

But this semester she enrolled in a college-level computer science course taught by Stanford professor Patrick Young — and her plans are changing.

“In the beginning, I was really struggling," she said. "I was going to drop the class,” which involved more independent study than she was used to. But her high school teacher, Lindsay Humphrey, encouraged her to stay.

“This class made me realize that I could probably handle the workload that’s given at universities like Stanford or known schools,” she said. “And I think that’ll help in my future.”

Computer Science 105 is offered as part of a program by the National Education Equity Lab, a New York-based nonprofit founded in 2019. The organization partners with elite universities across the country to offer college-level courses to high school students. The curriculum is not toned down, but students receive added support from high school teachers, university faculty and teaching fellows.

Leslie Cornfeld, a former federal civil rights prosecutor and founder of the Ed Equity Lab, said that in speaking to school administrators and students she realized that education equity is “the civil rights issue of our time.”

Research has indicated that high-achieving students from low-income families don’t apply to selective universities at the same rate as students with equal test scores and grades from high-income backgrounds. The Ed Equity Lab aims to tackle the trend, called "undermatching."

“We would travel to Title I, underserved high schools and even the most talented students didn’t believe they were college worthy and couldn’t get on the radar of competitive universities despite best efforts,” Cornfeld said. At at a Title I school, at least 40% of students come from low-income households.

The nonprofit hopes to bring its program to 25% of Title I school districts throughout the U.S. in the next three years.

Los Angeles schools Supt. Alberto Carvahlo had worked with the Ed Equity Lab when he was superintendent of the Miami-Dade County school district. In his August back-to-school address, he announced that the program would be part of his strategy for college readiness.

In the spring, the courses offered through the program in Los Angeles Unified schools will more than double, from nine to possibly more than 25, Carvalho said.

Classes offered through the Ed Equity Lab are taught by professors via pre-recorded videos. Students watch the videos weekly on their own time and then meet in class with a high school teacher who offers college readiness tips and support. Teaching fellows, who are students and alumni of the universities, offer live support via Zoom.

The classes range from core algebra and writing courses to liberal arts classes, such as the University of Pennsylvania’s “Grit Lab: The Psychology of Passion, Perseverance and Success” and Spelman College’s “The Education of Black Girls.”

The Birmingham high class has inspired a newfound enthusiasm among many students for computer programming. Others have ruled out coding as a career but have gained confidence that they can complete a university level course.

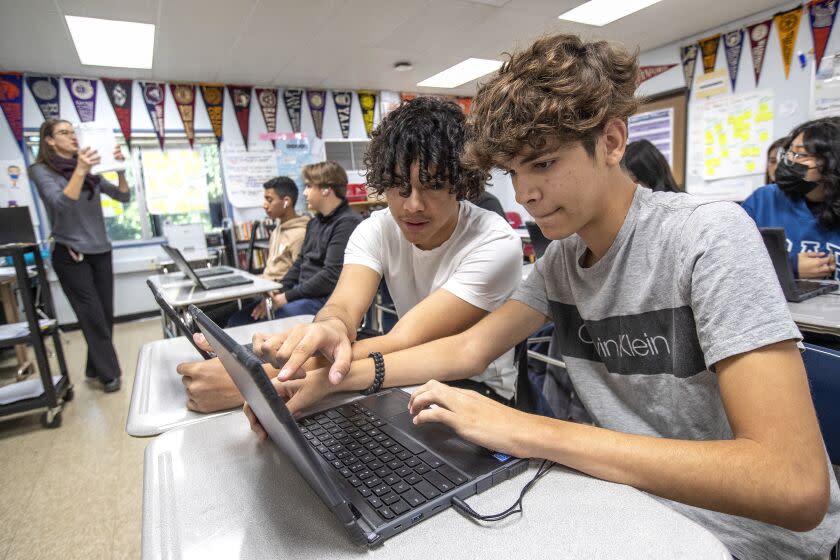

During a recent class, Jennifer and her partner, Vianney Silva, worked together as they were introduced to Python and interacted with Stanford teaching fellows, who infuse lessons with positivity.

This assignment was more challenging than the HTML and CSS courses they had completed in previous weeks. The girls started their assignment correctly, but quickly met a roadblock.

When teaching fellow Zach Barnes jumped into their Zoom breakout room, he asked the students if they needed help. The girls were quiet for a few moments before Vianney declined.

Quietly, she said “We don’t have any questions.”

“Are you sure? I can help you with anything you need,” Barnes pressed patiently as the girls seemed to decide whether to speak up, too shy to turn their cameras on. The girls flipped through their notes and whispered to each other before Vianney took him up on it.

“So we make a For Loop right?” she said, referring to a coding process that would allow them to go through the information from the files they were working with.

The students shared their screen and Barnes affirmed their instincts were correct — and the girls went back to work.

The soft-spoken Vianney said she was "a little bit" intimidated speaking up, because Barnes is a Stanford graduate and an adult, but this class has taught her the importance of asking for help. She's become a regular in office hours, offered daily by teaching fellows.

Vianney said "it's pretty amazing to me" to be taking the same class as Stanford students. The 15-year-old loves problem-solving and math, and wants to study computer science and engineering in college.

In another breakout room, two students asked teaching fellow Terrell Ibanez why there was a small discrepancy in one of the numbers in their code.

“Oh that’s actually hard to explain. That happens a lot in computing,” he said, explaining that the difference was significant for NASA programmers but not in this class.

“These little numbers matter because they compound as you travel through space. It doesn’t matter here … but that’s a good question.”

Erick Salcido, 16, said he wanted to quit the class at first, because "it was too much." Unlike in his other classes, he can't leave assignments to the last minute. It takes him days or a week to finish an assignment, and he wasn't used to that, he said.

“We come from Mexico and my mom told me, ‘To be honest, if you told me this in Mexico I would let you quit school and I would put you to work.’ ”

It was a sobering realization for him.

“I thought OK, this is a really good opportunity.”

Now a career in web development is appealing. He likes the feeling when he runs his code successfully — and he knows web developers can make a lot of money.

It would mean a lot to him and his family, who immigrated from the Mexican state of Jalisco in 2019 and just a few years ago struggled to even find housing. He plans to make his parents proud.

Frida Gonzalez, 16, boosted her GPA after taking the computer class last year and has given speeches about her experience for the Ed Equity Lab in front of “important people,” something she couldn't imagine before.

Frida proudly says she is applying to Stanford next year. She has always wanted to study medicine and become a pediatrician, but after taking CS 105, she may dabble in biotechnology or bioengineering.

“Once I got scores back for my assignments, I was like, oh, I got a good score and this is exactly what [Stanford students] are doing. It gave me the confidence to say, OK, maybe Stanford isn’t so far away.'”

William Lopez, 15, said the class has been more challenging than any other. It takes him hours to take good lecture notes, and he has to be good at time management to balance this independent study, his other classes and sports.

He hopes to study mechanical engineering at Stanford, UC Berkeley or MIT. But after taking the class, he has a newfound interest in computer programming.

“I found out that I actually really like computer science and that interests me as much as mechanical engineering, and that I actually want to do a double major or something like that,” he said.

Succeeding in the class has made him feel more confident in every other class. “It kind of gives me that mentality, like, it’s not as hard as this, so I know I can do it."

He has his goals set on becoming a NASA engineer.

“Dream big, you know?”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.