High water and more blooms on Lake Okeechobee spark worries about future algae woes

It’s summer in Florida, and that means longer, hotter days, near-daily deluges— and algae blooms.

They happen every year in many of the state’s waterways, but recent conditions in Lake Okeechobee, Florida’s largest and most important lake, have some advocates worried that this season could bring more major, harmful blooms.

“Anytime we have a high lake going into the wet season and we have the presence of blue-green algae, it is cause for concern,” said Chris Wittman, co-founder of Captains for Clean Water. “But there’s so many variables that it’s hard to predict what we’re going to see.”

Lake O can only hold so much water. Some of it trickles down south, where it gets sucked up by thirsty farmers and helps restore the Everglades, but the major way the lake gets drained is through releases to the east and west via the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers.

Lake Okeechobee is currently 14.09 feet high, about two feet higher than the Army Corps of Engineers, which maintains the lake, likes to see it in June. Recent heavy rains, plus leftover swell from Hurricanes Ian and Nicole last year, have left lake levels higher than usual. This time last year, the lake was about 15 inches lower.

It’s also pretty dirty. The lake is chock full of nutrients from farms, leaky septic and sewage tanks and other nutrients that form the perfect food for algae. And fresh rains wash in even more fertilizers and human waste, which makes blooms all the more likely.

Unfortunately for Florida, the rainiest times of the year, when lake levels run highest and discharges are most common, is also when algal blooms form. And the algae on Lake O isn’t always harmless. In high concentrations, it can be toxic to humans.

If algae-clouded water from Lake O gets sent west and east in high enough volumes, it can multiply, clogging marinas and rivers with organic matter as thick and green as guacamole. In 2016, and again in 2018, those algal explosions were devastating to the economy of coastal Florida.

Bloom on half the lake

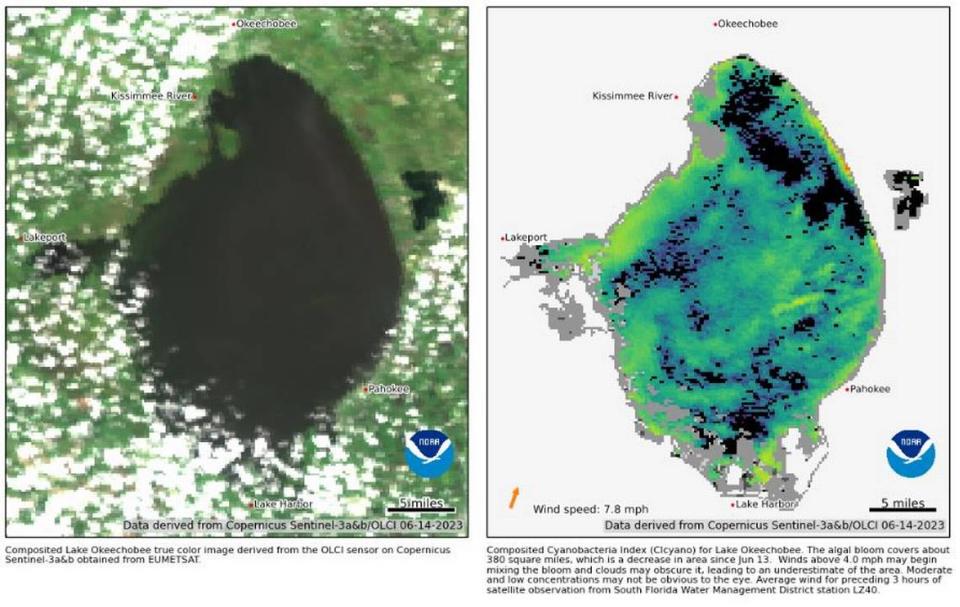

As of Wednesday, NOAA satellites measured about 380 square miles of algae bloom, a little under half of the lake’s total surface.

The latest tests from Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection found moderate to high bloom potential on about 70% of the lake, and state officials found slightly more algal samples than usual for early June.

Of the 55 spots sampled last week, 38 of them contained algal blooms. Some of them also contained harmful algal blooms, and a handful contained toxic cyanobacteria at levels dangerous to human health.

The EPA considers microcystis aeruginosa, the toxic cyanobacteria also known as blue-green algae, harmful to humans at a concentration of 8 parts per billion. While most spots tested in Lake O showed levels far lower — like .43 parts per billion — several had levels over 11 ppb.

“Right now, is the risk of that happening there? It is,” Wittman said. “The concern is there.”

But unlike in 2016 or 2018, Wittman said, the Army Corps has become much more sensitive to the potential of economic and ecological consequences to large water releases.

“Everybody is a lot more aware of what can happen than they were a few years ago,” he said.

No planned releases for now

That was clear on a Friday press call, where Col. James Booth, the Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville district commander acknowledged concerns about algae and said the state was working on culling the blooms.

For now, the Corps is not releasing any Lake O water to either coast. That could change if water levels get higher.

Booth said at 16.5 feet of water, his concern starts to shift from the possibility of sending blooms to the coast to the structural safety of the dams and levees holding in the massive lake.

“Above that level, we’re thinking about it, we’re talking about it. But just because we’re going over 16.5 doesn’t mean there’s a risk,” he said. “It all depends on what the timing is. There’s no particular number that triggers a decision for a release.”

Looking to the future

A continued spate of rainy days, or even a particularly soggy tropical storm or hurricane, could nudge the Corps closer to a decision to release water. But with the recent renovation of the Herbert Hoover Dike, a massive wall holding water inside the lake, Booth said he’s more confident in holding onto more water.

In the long term, Everglades advocates and government officials are working on plans to send more water south, both through the new lake management plan debuting later this year and the constriction of multiple new projects designed to store, treat and flush the cleaned water south.

It’s the $4 billion ‘crown jewel’ of Everglades restoration. But will it be enough?

The biggest and most controversial is the Everglades Agricultural Area reservoir, which began construction earlier this year and has split the normally tight-knit Everglades advocacy community over concerns it won’t work, or could even worsen the problem.

Wittman, whose group is a wholehearted supporter of the project, said he believes that once its built, it would help Florida avoid situations just like this.

“The more projects come online, the more capacity we have to increase those flows south, where they used to flow naturally,” Wittman said. “We need these projects done as quickly as possible.”