Higher food prices hit South Bend-area food pantries with lagging supplies, high demand

SOUTH BEND — Rain pelted cars in line at a drive-thru food pantry as drivers spoke about the pinch of inflation. Not only on their grocery bills.

They are part of a recent surge in demand at pantries, which now are also coping with a drop in food they’re receiving — and considering limits on this food aid — all thanks to the same economic forces.

“Everything is going up, and we’re not getting more money,” retiree Christina Smith of South Bend said as she waited at the Food Bank of Northern Indiana for food for herself and the two grandsons she’s raising, ages 10 and 14, whose appetites have grown.

No more small bites of this and that for the kids. She said, “Now they want a full-course meal.”

As one of many seniors who frequent food pantries, her income from Social Security may have risen, but she added, “They took that to pay my medical bills.”

Ball State University economist Michael Hicks points out that Social Security offers a “fairly generous” adjustment for inflation, but, he added, “The problem is you have to wait several months for it to kick in.”

The prognosis isn’t clear for the inflation that has driven up the price of several grocery items — some more than others — as Hicks attests, “We don’t know how long this will last.”

Various economic forces are driving food prices, including Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has impeded wheat and grain imports and driven up fuel costs. This year’s bird flu epidemic led farmers to slaughter and discard millions of chickens, raising meat and egg prices.

Consumer prices hit a peak in March not seen since 1981. Overall, prices were 8.5% higher than they were a year earlier. That edged down in April to 8.3%, but still far ahead of normal.

Food prices at the grocery store jumped 10.8% in April from a year earlier, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The country’s “core inflation” rate — apart from the volatile prices of gasoline and food — was 4.5%, Hicks said. That combines with a roughly 4% rate in the “sticky price index” for prices that aren't likely to come down.

The longer that inflation persists, Hicks said, the more likely that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates. That would mean a slower economy, and the first jobs to be lost would likely be in construction trades as fewer homes are built (mortgage rates are already creeping upward).

With more inflation, he said, there’s also the possibility that the economy slips into a recession in late 2022 or early 2023.

The crunch of food prices could go on for years if you listen to folks like Art Cullen, editor of the Storm Lake Times Pilot in rural northwest Iowa, who has a front-row seat to the perils of odd, climate-change weather such as dust storms that spin out of hot, dry, degraded crop soils. He opines in the Washington Post how food production around the globe will continue to suffer from agricultural diseases and other calamities as long as the climate is out of whack.

He wrote: "Climate change, livestock pandemics enhanced by huge concentrations of critters, and growing human population will increase food costs, absent a leap forward in technology."

For the homebound: United Way of St. Joseph County taps DoorDash for free deliver to people in need

'People are hurting right now'

For now, as inflation persists, Food Bank CEO Marijo Martinec said no decision has been made yet, but the agency may have to cut back on how much food a client gets per visit.

“We are looking at different scenarios to see how we can continue serving,” she said.

One of the charities it supplies, the Clay Church Food Pantry in South Bend, just recently started to limit clients to just one visit per month rather than two. Director Sue Zumbrun said that came after more than 800 households sought food in April, a leap from what typically has been 400 to 600 households in a month. Demand, she said, is steeper than it had been in the midst of the pandemic.

“It makes me feel bad,” Zumbrun said, surmising that clients are likely trying to save on food so they can afford the now-higher-priced fuel for their cars. “People are hurting right now.”

Among the pantries and charities that seek food from the Food Bank to help needy households, demand was up 18% in St. Joseph County for the first four months of 2022, compared with a year earlier, Martinec said. Likewise, demand for that time span was up 43% in Elkhart County, 31% in LaPorte County and 27% in Marshall County.

The Food Bank’s own drive-thru pantry in South Bend served 50% more households in 2022’s first four months, compared with last year.

Meanwhile, Martinec said, the food going out was down 26% because of a similar drop in what the Food Bank has received.

The story is repeated nationwide. The Food Bank is just one in a national network, Feeding America, where 85% of food banks reported demand had increased or stayed the same in February, combined with 55% who've seen a drop in donations in the past six months. Its CEO, Claire Babineaux-Fontenot, said in a press release, "In the coming months and years, we are facing a historically unprecedented set of simultaneous challenges."

November 2021: South Bend area food pantries face the same issues as consumers: high prices and shortages

Surge of help is over

At Clay, Zumbrun said, the pantry's shelves have gone from “too much” during the pandemic to “too little.” Part of that, she said, is because it’s now getting government commodity foods every few months rather than once a month.

Early in the pandemic, Martinec said “we were really lucky” as the public donated more and as the USDA shipped more products to food banks. The U.S. Department of Agriculture also provided meat, produce and dairy for a year and a half with the commodities. As well, the United Way of St. Joseph County responded with dollars for food aid to various charities as many people, especially in 2020, suddenly were without work.

The bonus food aid has ended. Now the influx of government commodity foods is back to what it was in 2017 and 2018. The difference, Martinec said, is that pantries are now seeing more clients.

Supply chain issues also slow the arrival of USDA food. The Food Bank has ordered goods that have yet to arrive, Martinec said, adding, “It’s getting a little better.”

Back at the pantry line, one man turned down the day’s food offerings, saying, “Is that all?” He and his wife wanted milk. Martinec explained that milk isn’t always available, but the pantry offers it when it is.

She said the Food Bank often buys staple food for pantries while also passing along the cost. It recently paid $2.58 per dozen eggs.

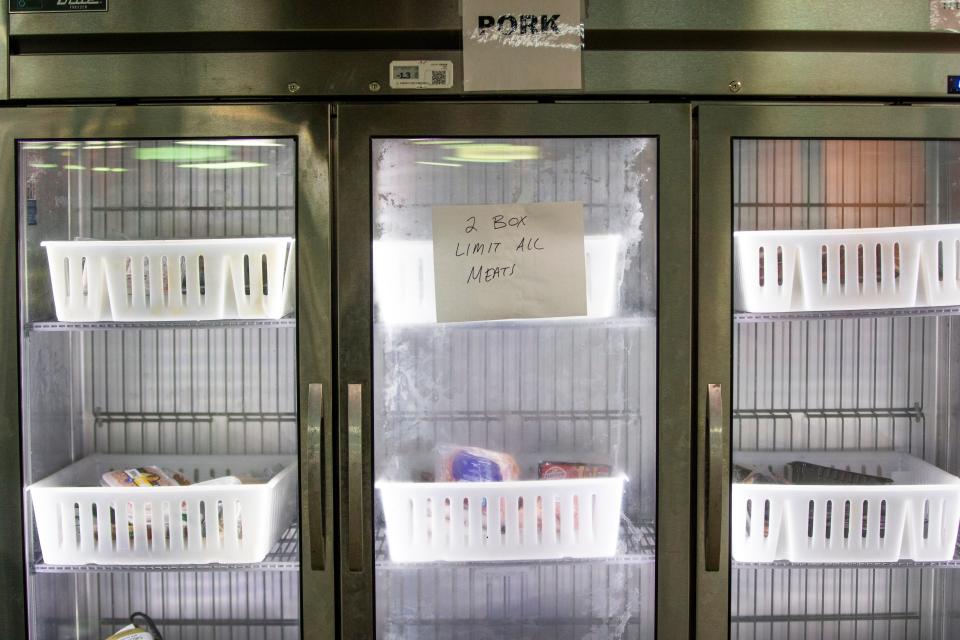

Some stores call for the Food Bank to pick up spare meat, but the stores have less to give. The Food Bank’s freezers were low on meat last week.

Alternatives

Smith, whose grocery bills can hit $200, said she and her grandsons have been going without meat at times lately. They’re still getting their protein. They turn instead to more beans, eggs and dairy, she said, noting, “They love black-eyed peas.”

Also in line, Tony of South Bend, who didn’t give his last name, said his construction wages are about the same but said rising costs are causing him to cut back on “just about everything,” from vacations to bowling to movies. He said he’s still replenishing the lost income and dented 401(k) from the stretch of the pandemic when he didn’t work.

Hicks, the economist, notes that “actual wages” are down because inflation is eating into workers’ income.

One woman, driving a minivan, said she works just one day a week while her husband’s weekly take from a construction job, about $600, isn’t enough for them, their two kids and a grandson. She, like others in line, emphasized the high cost of gasoline.

Martinec said the Food Bank, too, is spending more than it had budgeted to fetch and deliver food. Diesel, which its trucks use, has been about $1 more per gallon than gasoline.

The Food Bank would like to allow its on-site pantry clients to visit every 15 days, which it started last summer, but it may consider reducing how much food it gives out per client.

The agency is also trying to ramp up its mobile food pantries at sites scattered through six counties while also trying to ensure the food can actually make complete, healthy meals.

As well, the United Way of St. Joseph County's People Gotta Eat initiative, which supports about 22 pantries, was able to keep its donation barrels out longer during the Christmas holidays, Jim Baxter, the United Way's director of community impact and empowerment, said.

And, he said, the new partnership with DoorDash that the local United Way started early this year — to deliver food and other basic needs to the homebound and to those who have trouble making it to pantries — has delivered food for thousands of meals in the past four months.

The letter carrier union’s annual Stamp Out Hunger food drive returned May 14 after a two-year pandemic hiatus, always coming at a time when pantry shelves run low and ahead of a typically strong summer demand. It brought in 64,099 pounds of food donated at mailboxes in St. Joseph County for the Food Bank, plus perhaps 10,000 or so pounds in bins at grocery stores, Martinec said. That was down from roughly 100,000 pounds, give or take, in years past.

How to help

Both food and cash donations help the Food Bank and pantries, though cash typically goes further to help charities get more of what they need. Food Bank of Northern Indiana is at 702 Chapin St., South Bend, Indiana 46601; 574-232-9986; feedindiana.org.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: Food Bank of Northern Indiana pantry donations drop inflation climbs