Highways aren't numbered randomly. Here's how I-71, I-75 got their names

We all probably spend more time on our highways than we’d like. Road trips. Commutes. Visiting friends or family. But also, we probably don’t think much about the history of these roadways.

Some people do. Jake Mecklenborg has devoted an entire website, Cincinnati-Transit.net, to Cincinnati’s transportation infrastructure, from freeways to bridges to inclines and viaducts.

There’s a lot more to the history than just building roads.

Before cars, people traveled long distances by train, steamboat, canal boat, stagecoach or even by foot, depending on where they were going. Starting in the 1890s, electric streetcars known as interurbans carried passengers quickly between cities. But with automobiles, particularly the mass-produced Model T touring cars, people could go wherever they wanted. As long as there was a road.

Our History: How do you get there? The many methods of travel in Cincinnati’s early days

The need for transcontinental roadways

Early auto routes connected regions of the country as early as the 1910s. The National Road, which stretched from Maryland to Illinois, had been a wagon and foot trail since 1811, but with the introduction of automobiles, it became part of the National Old Trails Road in 1912, and later part of U.S. Route 40.

The Dixie Highway, constructed between 1915 and 1929, was a network of roads connecting the South to the Midwest from Miami, Florida, to Chicago and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula via two main arteries. The portion through Cincinnati was U.S. Route 25.

By the 1930s, it became evident there needed to be better roadways for travel across the nation.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for the Bureau of Public Roads to submit a feasibility study for six cross-country superhighways, three running east-west, three going north-south. One of the proposed superhighways would have connected San Francisco to Philadelphia, passing through Columbus.

The study determined that the amount of transcontinental traffic wouldn’t be enough to sustain the system through tolls, but it did recommend a 26,700-mile network of regional non-toll highways that would take advantage of existing roads and include bypasses around major cities. That became the basic model for the future interstate system.

But that would have to wait. While the nation was occupied with World War II, plans went ahead with local highways instead.

The beginnings of Interstate 75

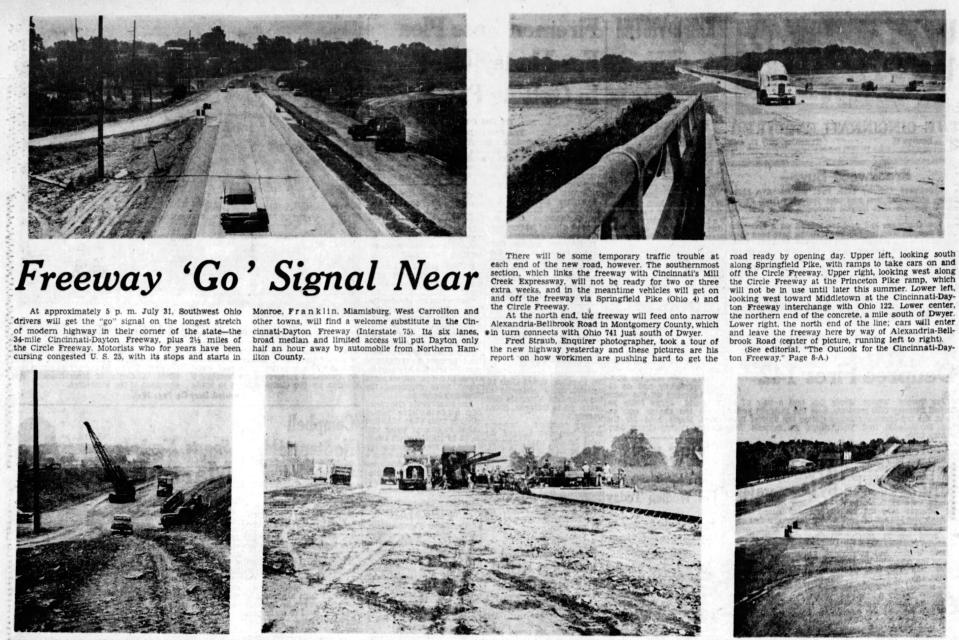

What became Interstate 75 began in the 1930s as a plan for a 50-mile “regional superhighway” connecting Cincinnati and Dayton, according to Mecklenborg’s research. The road followed the old Miami and Erie Canal route through the Mill Creek Valley. Mill Creek was a remnant of the ancient Ohio River, known in geological terms as the Deep Stage Ohio River. That’s why the path slices through the region’s many hills.

The first segment, known as the Wright-Lockland Highway, was quickly completed in 1941 to access the Wright Aeronautical plant (later taken over by General Electric), which built aircraft engines during the war.

The Cincinnati Metropolitan Master Plan in 1948 identified the 10-mile section of highway along U.S. Route 25 to be built through Hamilton County as the Millcreek Expressway. The master plan also proposed the “Third Street Distributor,” which became Fort Washington Way, to cross Downtown near the riverfront and connect the major highways.

Highways to connect Cincinnati to Dayton and Cincinnati to Cleveland were also under construction at that time.

Interstate system was the biggest public works project in history

Finally, with the emerging importance of cars in America and funding finally secured, all the highway plans were swept into an umbrella federal program.

On June 29, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 into law. It established the construction of a 41,000-mile interstate highway system, to cost $25 billion ($275 billion in 2022). This would incorporate many of the existing highways and those under construction.

So then, the Cincinnati-Dayton Highway connected to the Millcreek Expressway as one route. Many regional and state routes were also identified as federal interstate routes.

As with any major undertaking, there were detractors.

“A swelling propaganda barrage of distortions, half-truths and plainly dishonest generalizations is threatening to sink the biggest and most important public works project ever attempted in this or any other country – the interstate highway system,” The Enquirer’s Washington correspondent Philip M. Swatek wrote in July 1960.

Opponents with axes to grind fought over politics, taxes, funding, rising costs and rural vs. urban priorities, Swatek explained.

The cost was a real concern. The price tag of the interstate highway system was already up to $40 billion by 1960, then eventually ballooned to a whopping $114 billion over the 35 years of construction.

Highways permanently changed the American landscape. Communities were built around automobile access. People moved out of cities to live in suburbs. Small towns along the old highway paths withered as traffic stayed on the freeways. Identical truck stops and fast-food eateries popped up at every exit.

In his 1962 book “Travels with Charley: In Search of America,” John Steinbeck wrote, “When we get these thruways across the whole country, as we will and must, it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing.”

Method behind names and numbers

But what to call these highways? Each segment had its own name, so it was confusing.

In 1958, Enquirer reporter George Amick complained that the name North-South Freeway was applied to both the Cincinnati-Dayton-Toledo route and the Cincinnati-Conneaut road to reach the northern-most city on the Ohio-Pennsylvania border.

The former would be called Interstate 75, superseding the old Route 25. But Amick had a suggestion for the other road.

“Why not call the Cincinnati-Conneaut road the ‘Four-C Freeway’?” Amick mused. “The name would refer to the terminal points … and the two major cities between – Columbus and Cleveland. Headline writers, at least, would be grateful!”

It turns out the eventual name, I-71, also takes up very little headline space.

There is, in fact, a method to the numbering of highways and interstates.

According to the Federal Highway Administration, interstates with odd numbers run north-south; even numbers run east-west. For north-south, lower numbers start in the west (such as I-5 in California). For east-west, lower numbers start in the south.

Circle interstates around urban areas (known as circumferential beltways or ring roads) are given three-digit numbers – the number of the main route plus an even-number prefix. So, the circle route connecting to I-75 around Cincinnati is I-275. The circle connected to I-71 is I-471.

Major north-south interstates end in a 5; major east-west routes end in 0.

Greater Cincinnati's other interstates

The region’s other major expressways include:

I-74: Connecting Indiana to Cincinnati; construction lasted from 1958 to 1974. The route follows Mill Creek’s west fork (thus, West Fork Road) through Mount Airy Forest.

I-71: Connecting Cincinnati to Columbus and Cleveland, parallel to U.S. Route 22. It was mostly completed in the early 1960s, with some construction into the 1970s. The Lytle Tunnel, burrowed beneath Lytle Park, was completed in 1969, connecting I-71 to Fort Washington Way (finished in 1961).

Norwood Lateral (Route 562): The three-mile expressway running through Norwood to connect I-75 and I-71 opened in segments between 1960 and 1974. It follows the basic pathway intended in the 1920s to be a surface-running portion of the never completed subway, according to Mecklenborg.

Ronald Reagan Cross County Highway (Route 126): Connecting I-75, I-71 and I-275, though it took decades (from 1958 to 1994) to finally reach them all. In 1992, the Hamilton County commissioners – all Republicans – approved adding the former president’s name to the Cross County Highway.

All the local interstate roadways have been seemingly undergoing upgrades and construction ever since.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: How I-75, I-71 and other major interstates got their names