‘Go out and get it’: Hilton Head business legend Abe Grant dies at age 85

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

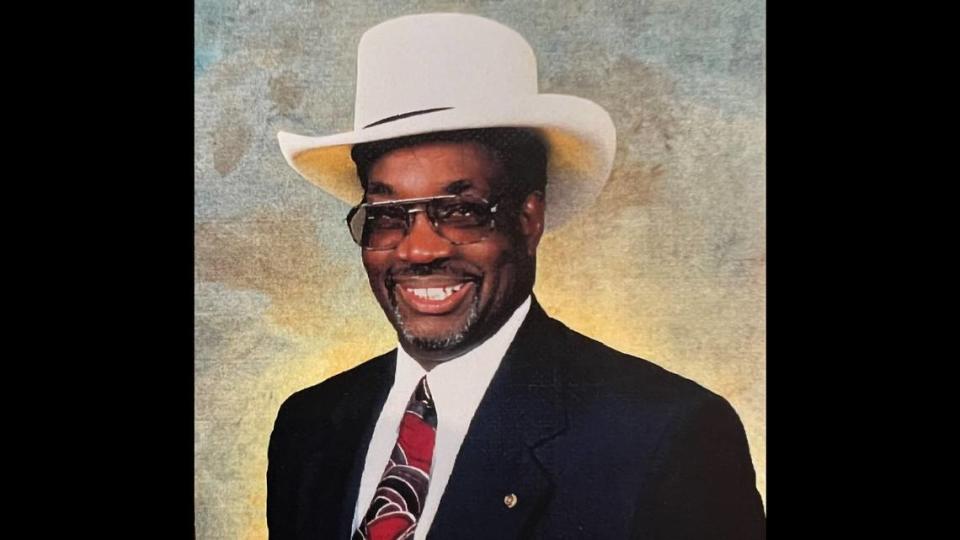

Abe Grant was always the grand marshal in his remarkable parade through life on Hilton Head Island.

The legendary entrepreneur who opened his first store on the side of U.S. 278 at age 16 fit the part as he flashed a big smile beneath a broad-brimmed hat as he cruised in a shiny red 1964 Ford Falcon convertible.

He built that store with the defective boards from one of the island’s three sawmills in the late 1950s. He would later move across the two-lane highway near Singleton Beach Road, build a home for his growing family, and over the years expand his emporium to include pool tables that were about the only recreation on Hilton Head in the late 1960s; then a meat-and-three restaurant where sheet-rockers and lawyers ate cheek by jowl; then Abe’s Native Island Shrimp House where his wife, Charliemae, produced Gullah staples like shrimp and grits before they were considered high cuisine; then Abe’s Driftwood Lounge with live music; and a string of motel rooms out back, where he was addressing “workforce housing” before there such a term.

Even after selling his land, Abe Grant couldn’t lay off the gas when he retired to the pinochle table.

“Setbacks can’t stop you,” he told me. “We all had setbacks, but we scuffled it out. The world owes you nothing. You’ve got to go out and get it. We have too many who are blessed and don’t even know they’re blessed. They have and don’t even know they have.”

He became the face of Hilton Head for many years as his business was one of the few things you’d see between the bridge and Coligny Plaza.

As a child, the fourth-generation islander became all too familiar for his tastes with the south end of a north bound marsh tacky. As a young man, after trying life in Miami, he saw business potential on the island and came home, never to bellyache like the rest of us about massive island change.

He attended a two-room elementary school on Mathews Drive and a four-room junior high on Beach City Road before leaving school in the eighth grade. But he was street-wise when island roads were deep ruts in sand and when they became a six-lane blur of cars with tags from all over North America.

On Monday, Abe Grant moved his parade to the streets paved with gold when he passed away at his home off Spanish Wells Road at age 85.

THE WORKFORCE

Abraham Grant Sr. was raised by an aunt and uncle, Willie and Beaulah Grant Kellerson. They farmed and fished in the Chaplin community. And sold moonshine.

At age 12, Abe was making the best moonshine on the island under the tutelage of his uncle, he told The Island Packet in a story recorded in the book “Remembering The Way It Was, Volume Two” by Fran Heyward Marscher Bollin.

He was introduced to Charliemae Smalls of Hampton County by her brother, Harold, a cook at the Sea Crest Motel. Harold would later open Harold’s Diner across the highway from Abe’s.

The couple that was to celebrate their 60th anniversary on May 3 had five children. They were the workforce, cooking and cleaning.

Abe held court at a large antique oak table, announcing each new business plan and everyone’s role in it. The plan for life was built on hard work, a good education and devotion to church. Abe was a deacon at Mt. Calvary Missionary Baptist Church for 50 years.

Abe Jr. went into the Navy and now lives in Atlanta. He’s the keeper of the red Ford Falcon.

Lillian is a geophysicist, working with an oil and gas service company in Texas.

Carolyn is a recovering journalist with a post-graduate degree, now director of communications for the Town of Hilton Head Island and co-author of the landmark 2020 book, “Gullah Days: Hilton Head Islanders Before the Bridge.”

Tony works in IT for the Beaufort County School District and is a deacon like his father.

And Terry is a Realtor and musician with a master’s degree in jazz performance from the American Conservatory of Music. She has a doctorate in education and teaches aerospace engineering at the Jasper County high school.

Abe had two other sons who worked in the business in later years, Travis and Rawn.

DADDY KING

Lillian Grant Flakes has degrees from Spelman College and Georgia Tech but says her true education came from her parents.

“Being able to express yourself clearly and precisely,” she said. “Not being afraid to stand your ground. Having goals. Setting goals. Being willing to pivot, and then being able to pivot quickly, adjust with the times.”

Abe stood his ground when he put up his first string of neon lights. A couple of hours later, he got a call from pioneer island developer Fred Hack. He was told it had been decided we wouldn’t do neon here. Abe pointed out he was not invited to be part of said decision. He went along with the new standard but got $90 out of Hack and Sea Pines.

His business never had trouble attracting customers, especially visiting African Americans.

Jesse Jackson would come to the back door, announcing he wanted the usual: a large fried flounder and lemonade.

Malcolm X’s wife, Betty Shabazz, was a regular, as was “Good Times” star Esther Rolle.

From the Southern Christian Leadership Conference came co-founder Joseph Lowery, Andrew Young and the Rev. Martin Luther “Daddy” King Sr.

They would often hand the menu back and say they wanted the “house pot” — whatever the staff was eating in the back, the good stuff.

The Native Island Business and Community Affairs Association held all of its foundational meetings at Abe’s.

Abe was a longtime member of the VanLandingham Rotary Club and a board member of the Palmetto Electric Cooperative Trust.

He loved to go fast, in the Falcon or his gold 1978 Lincoln Mark V. And in the boats he’d haul the family to Daufuskie Island in on Sunday afternoons.

On their annual family trip to Miami, Abe would entertain five kids in a station wagon with tapes of Al Green and The Consolers gospel duo.

On Sunday night as Abe Grant lay dying, the family put The Consolers on once again.

They played his favorite song, “May The Work I’ve Done Speak for Me.”

David Lauderdale may be reached at LauderdaleColumn@gmail.com.