A Hilton Head Island relic washed up thousands of miles away. Take a look at the journey

There was no reason for Iain MacVicar to point to Hilton Head Island on a map.

The salmon fisherman was content on another island over 3,700 miles away from the United States’ East Coast, off the northwest coast of Scotland. His home in North Uist, a community in the Outer Hebrides, is a place only accessible by ferry, flocked to by bird watchers and populated by about 1,200 people who sprawl its near-75,000 acres. It’s a peaceful life that relies on crofting, fishing and tourism, with locals who are grasping to keep the native Gaelic language.

But on a clear day three months ago, planted on a salmon boat at work, a discovery led MacVicar to the South Carolina island with 30 times the number of people on a much smaller piece of land.

“How strange,” MacVicar thought to himself that day as he peered at a seagull seemingly standing on the seas of Grey Horse Channel.

The bird wasn’t magic. But the fisherman wasn’t wrong. The seagull was perched atop a floating sign.

Pulled from the water, it was evident the sign had spent enough time during its transatlantic journey to become encrusted in goose barnacles and have its words weather-worn.

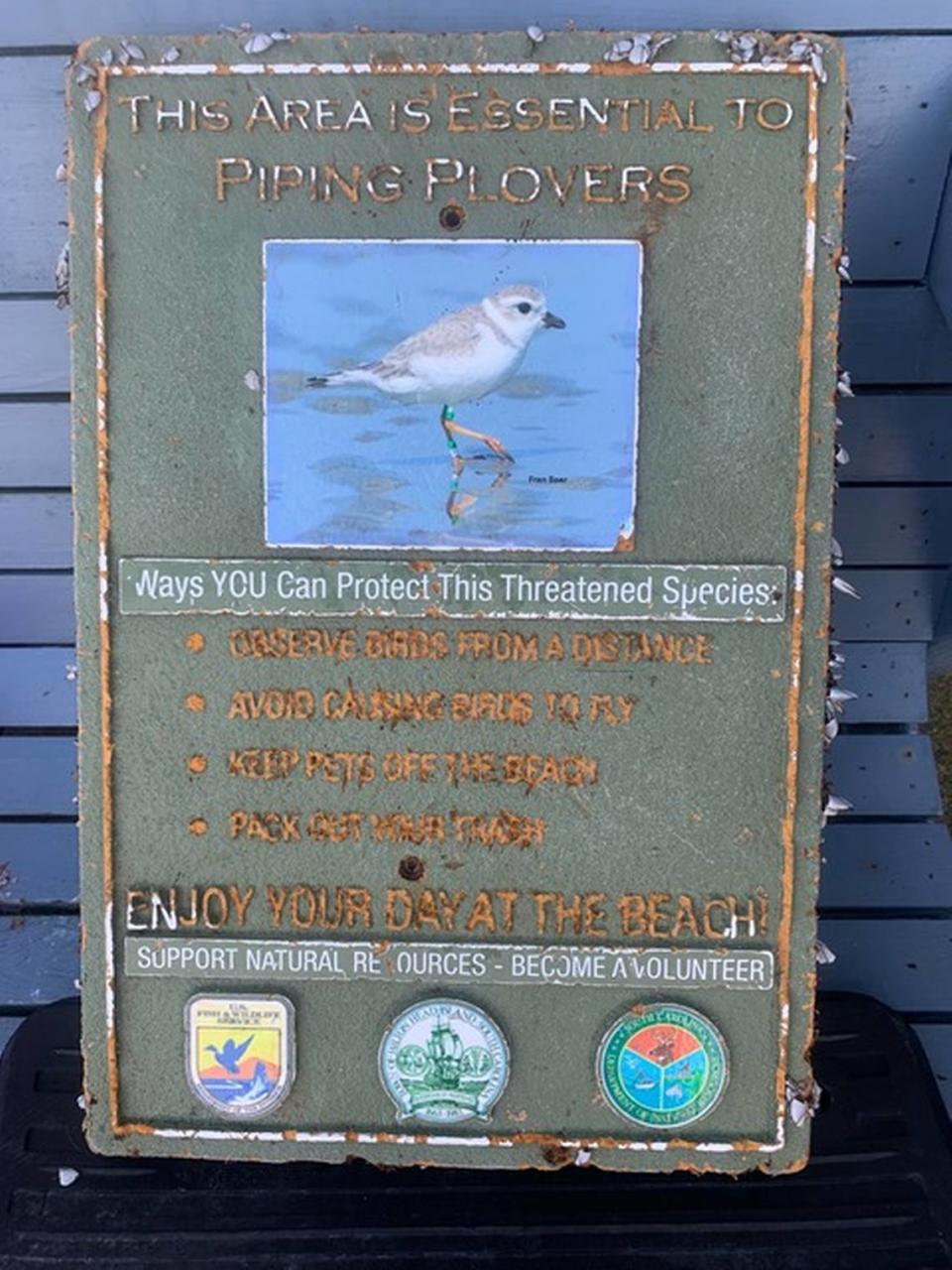

“THIS AREA IS ESSENTIAL TO PIPING PLOVERS” the moss-green plaque read.

For a sign well-traveled, it bore an unusually crystal-clear image of the tiny shorebird that over-winters in the Lowcountry. Emblems for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Hilton Head Island were faded but legible.

While MacVicar said the clusters of goose barnacles means the sign spent a long time in the water, he suspects it must’ve washed ashore somewhere before currents pushed it into the channel.

No one is quite certain how a piece of Hilton Head made it to a chain of Scottish islands. It’s likely the North Atlantic Gyre was its thousands-of-miles catalyst. And it’s possible the sign has been at sea for close to decade.

A sign for survival

When the Town of Hilton Head wanted to outline areas of Fish Haul Creek that were essential habitat for piping plovers, it took creative liberties, dressing up its signs from the standard plastic version made by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

That was about 10 years ago, said Melissa Chaplin, a biologist for the service.

Posted at high tide lines on the beach, where rack — Spartina grass that washes ashore — clusters to create a thick layer that piping plovers love, the signs were meant to keep people at bay. Shorebirds use the rack line as a resting area, napping in the camouflaging marsh grass that serves as a windbreak while they wait until their foraging areas are re-exposed during low tide.

Chaplin said the palm-sized birds are particularly fond of Hilton Head’s “heel” of the island’s foot shape. There, the wave energy is lower and has little gullies that form where organisms like worms and small shrimp settle and it serves as excellent feeding grounds.

Smart about their over-wintering habits, the sand-colored shorebirds that flock to Hilton Head aren’t much different from their human snowbird counterparts. Rest, feast, walk the beach and repeat. By November, piping plovers are usually settled and won’t move much until February, Chaplin said. Late-March marks the peak for migration north headed to breeding grounds.

“Pair up, put some eggs on the ground, hopefully hatch with the first attempt, and then raise the chicks,” Chaplin said. “Then they’re out of there.”

While the cycle is efficient, it isn’t always straightforward. A cog in the wheel can severely hinder the birds’ path.

Dogs rushing into the shorebirds’ habitat, people stomping through and storms upending beaches can disturb piping plovers, which, over time, causes them to expend more energy responding to the threats. The draining disturbances take time away from the normal napping and eating schedule.

The more a site is disturbed, the less a plover weighs and annual survival rates drop.

Hilton Head typically has the largest population of piping plovers in the state, Chaplin said. But a five-year study comparing varying degrees of disturbed sites in Georgia and South Carolina, revealed that plovers that came to the island had the third-lowest survival rate.

Alerting beach-goers (and their four-legged friends) is vital in maintaining healthy resting and foraging habits so piping plovers’ can recuperate and beef up for the flight to nesting grounds. Hence the specially made signs.

Chaplin explained that the rogue sign MacVicar found was washed away from Hilton Head, likely caught in the North Atlantic Gyre, circulated for quite a while and made it to Scottish salmon fishing waters.

“It’s definitely possible,” Chaplin said of the journey. “There’s a loop current in the North Atlantic. That’s how sea turtles they kind of hang out in that for a while and then eventually they’ll go over to the Mediterranean area.”

Before this sign’s transatlantic journey, the furthest one had ever made it was to Florida’s coast.

Strength of the seas

The power of currents is one Iain MacVicar knows well. And it’s not only because of his work.

Nearly a century ago, St. Kilda, an archipelago 40 miles west of North Uist, relied on the strength of the sea to send messages.

Residents of the isolated islands would tightly seal packages and toss them into the water. They knew the currents so well that the packages would “more or less” wash up in the same area on mainland’s coast, MacVicar explained.

“Sometimes they’d miss the mainland in Scotland and it’d end up in Norway,” MacVicar said of the packages. “And sometimes they’d go a year this way, and a year that way, but you could predict eventually where they’d end up.”

However, no one could’ve predicted a South Carolina sign would make a transatlantic journey in the 21st century.

From their home in North Uist, Dorothy MacVicar, a part-time primary school teacher, kept looking at the piping plover sign and thought it was time to get the word out. She’d already mentioned to her sons, one of them who studying piping — both the Highland bagpipes and small pipes, that “Piping Plovers” would be a great band name. They turned her down.

On Oct. 23, she sent an email to the catch-all address for the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources.

“Travelled a long way!!” she signed off.

It had: 3,771 miles. That’s if the floating debris had taken a straight shot.