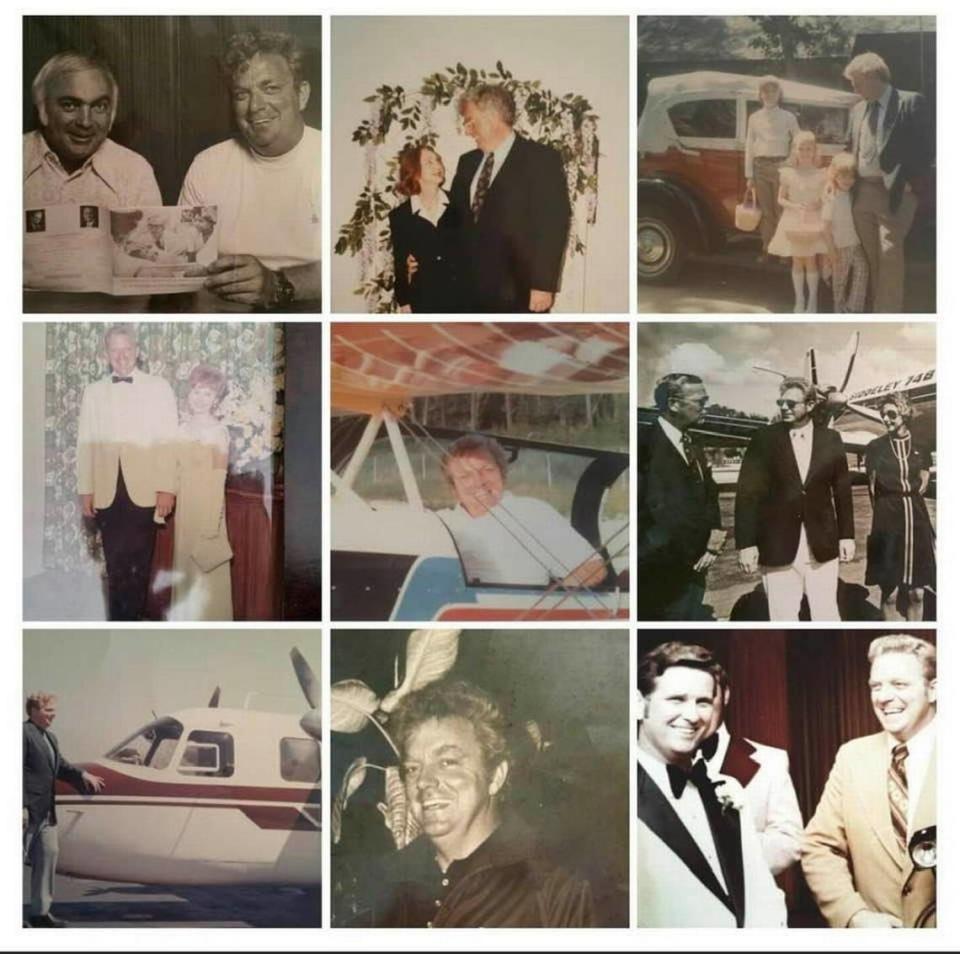

A Hilton Head pilot disappeared 25 years ago. His family remembers him as a hero

Pendleton Dunbar was waiting for her dad to walk through the door.

It was February 1996, and she sat with her younger brother and mother at the tiny Hilton Head Island airport. The last she’d heard, her father reported having vision issues and feeling dizzy while flying off the Georgia coast. He told air traffic controllers he was putting his tiny, twin-engine plane on autopilot.

Stewart Dunbar’s family waited until 5 a.m. for the man with an infectious smile to walk in and dispel their worries that something terrible had happened.

He never came.

Last Wednesday marked 25 years since the 58-year-old Hilton Head pilot, Realtor and former Palmetto Bay Marina operator went missing. His family and friends are still still searching for closure.

“My dad was like my best friend,” said his daughter, who was 24 when he disappeared. “I wouldn’t change the life I had with him for anything.”

Still, sometimes men who look like her father catch her off guard. She tries to make eye contact with them in airports or on bike paths in hopes that the last 25 years have been a bad dream and they recognize her.

“I always look for him. ... To this day I still think I see him.”

On Feb. 17, 1996, Dunbar was piloting a twin-engine Piper Aerostar on the way back from Swainsboro, Georgia, when he started feeling unwell.

He had told his wife, Dana, that he had a headache when he left their home earlier in the day. About 7:35 p.m., he radioed the Federal Aviation Administration air traffic control center in Jacksonville, Florida, to say he was putting his plane on autopilot.

It was the last time anyone would hear him speak.

Early life on Hilton Head

Stewart Dunbar spent much of his life on Hilton Head. His father, who had been in the funeral home business in Columbia, moved to the island in the early 1950s.

From the start, the son entrenched himself in island life.

He and his family operated Hilton Head’s first working marina, Palmetto Bay Marina, which he managed. He worked alongside Charles Fraser in the sales department at Sea Pines and became passionate about the thoughtful development of Hilton Head as a natural oasis. He later went on to work for Stoney Creek Realty in Bluffton.

Dunbar cared deeply for his fellow islanders. He was the president of the Jaycees, became one of the first volunteers for the Hilton Head Fire Department and was a charter member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

When he met his wife, Dana, also a fellow pilot, the two bonded over their love for the skies. There were so few people on Hilton Head that she would land her plane on the beach when she went to work at the William Hilton Inn on South Forest Beach.

Pendleton suspects her mother did this to impress her father.

With three children, the couple settled into an active life. They would often rack up 20 or 30 miles on their bikes, which Pendleton said must mean they rode around in circles on the tiny island.

She remembers growing up in a place with a single stoplight where everyone knew her dad and his cherry red convertible, teasingly referred to as “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.”

Her father, over 6 feet tall, would tool around Hilton Head’s quiet roads in that car, as well as the family’s brown Cadillac, with the family’s black poodle, Precious.

Pendleton’s older brother, Roger Dunbar, remembers his father as a “gentle giant,” who loved to take him offshore fishing and treated even young children with adult-like respect.

“He was very understanding, very caring. He always said ‘always be honest with me and I’ll be honest with you,’” Roger said. “I’ve tried to get that into my kids, too.”

‘Something was really wrong’

The Friday night before Dunbar left on his final flight, Pendleton told him over the phone that she loved him. She promised she’d see him the next day.

Then he set out in the twin-engine Piper Aerostar, which he piloted for the owners: former S.C. Gov. John West, island attorney Bill Bethea, Dr. Rajko Medenica and tennis instructor Dennis Van Der Meer.

That Saturday, Dunbar was flying to an unmanned airport in Swainsboro, Georgia, to show the plane to an interested buyer. According to Pendleton, the man never showed up for their meeting, so her father headed back to Hilton Head.

After he radioed to say he was switching to autopilot, his plane veered east out over the ocean. Navy pilots last spotted the plane about 465 miles off the coast about 10:35 p.m. They were unable to make contact.

Pendleton was working as a waitress at a bar in Savannah when she got word that she needed to call the airport on Feb. 17. It wasn’t uncommon for her to contact the airport to retrieve a message from her mother or father while they were flying.

This call, though, was different.

She remembers learning her dad wasn’t responding to radio calls, and just as quickly as she’d gotten the message, she was in a car heading to Hilton Head. When she arrived at the airport, her mother and younger brother, Chip Dunbar, were already there.

“Just from his eyes I could tell he was crying,” she remembers. “None of the men in my family ever cry; we just don’t do it. So I knew immediately when I saw Chip that something was really wrong.”

Coast Guard and Navy ships scoured an area about 400 miles off the coast looking for Dunbar or his plane. The search lasted through the weekend before it was called off.

A memorial service at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church on Hilton Head was held the following Sunday, Feb. 25. Later, friends organized a second gathering that included a flyover in Dunbar’s memory. The outpouring of sympathy showed the Dunbar family just how far-reaching their patriarch’s influence was.

“Our family had so much love in it, and dad was such a huge part of that,” Pendleton said. “He loved like there was no tomorrow. He didn’t just love his family, he loved everyone. He would do anything for anybody. He was a giver and a lover.”

Dunbar’s friends speculated that he put the plane on autopilot and headed out to sea so no one would be harmed if he crashed.

“If he understood he couldn’t control his plane and bring it down properly, he would take the only honorable choice and go where the odds of hurting someone would be minimized,” his friend John David Rose of Hilton Head told The Island Packet at the time.

That type of self-sacrifice and integrity wasn’t difficult to imagine.

In 1983, Dunbar was honored by President Ronald Reagan for saving a pilot from the cockpit of a burning plane. Reagan called his selflessness an “act of heroism.”

Wreckage off Florida

In August 2012, the Dunbar family got a glimmer of hope.

Divers off the coast of St. Augustine, Florida, had found plane parts 80 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Could they be from her father’s plane, Pendleton wondered?

She traveled to meet diver Joe Kistel, executive director of Think It Sink It Reef It in Jacksonville, and to see the metal he had retrieved from the ocean floor.

“I got a little tearful looking at this sand- and shell-encrusted piece of wreckage balanced in Joe’s hand. That was a moment where the reality of there is really wreckage down there, and it could be my Dad’s kinda merged into my reality. Seeing that piece was at best indescribable,” Pendleton told CNN at the time.

The family’s hope would be short-lived. Follow-up dives would determine that the wreckage was of a plane with a two-bladed propeller, not a three-bladed propeller like Dunbar’s plane had.

In November 2012, The St. Augustine Record offered a conclusion to the story of the wreckage. Two Navy planes had collided during a 1974 training mission, and one of the pilots was forced to eject with a parachute. He was rescued from the water, but his A-7 Corsair II sank 20 miles off the coast.

The 2012 wreckage discovery was an emotional roller coaster for the Dunbar family, but as the years have passed, they’ve come to appreciate the years they had with Dunbar, even if it means accepting they won’t see him again.

Pendleton’s younger son, Gage Malphrus, is the spitting image of his grandfather as a child. Gage’s curly blond hair reminds his mom of old photographs and family stories.

When her kids accomplish something, or there’s news on the island, she wishes she could share the little moments with the man who loved her first.

“I want to tell him all the stories that he’s missed, but I know that’s not going to happen,” she said.

Still, the family goes on. They look forward to the times when an old friend shares a memory or story about their father that they haven’t heard.

“I hope people remember him as a hero,” Roger Dunbar said. “He was absolutely my hero.”