Hingham author reflects on journey from Chicago's South Side to the South Shore

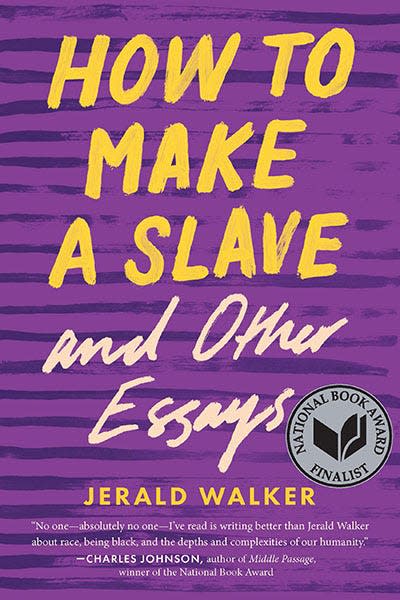

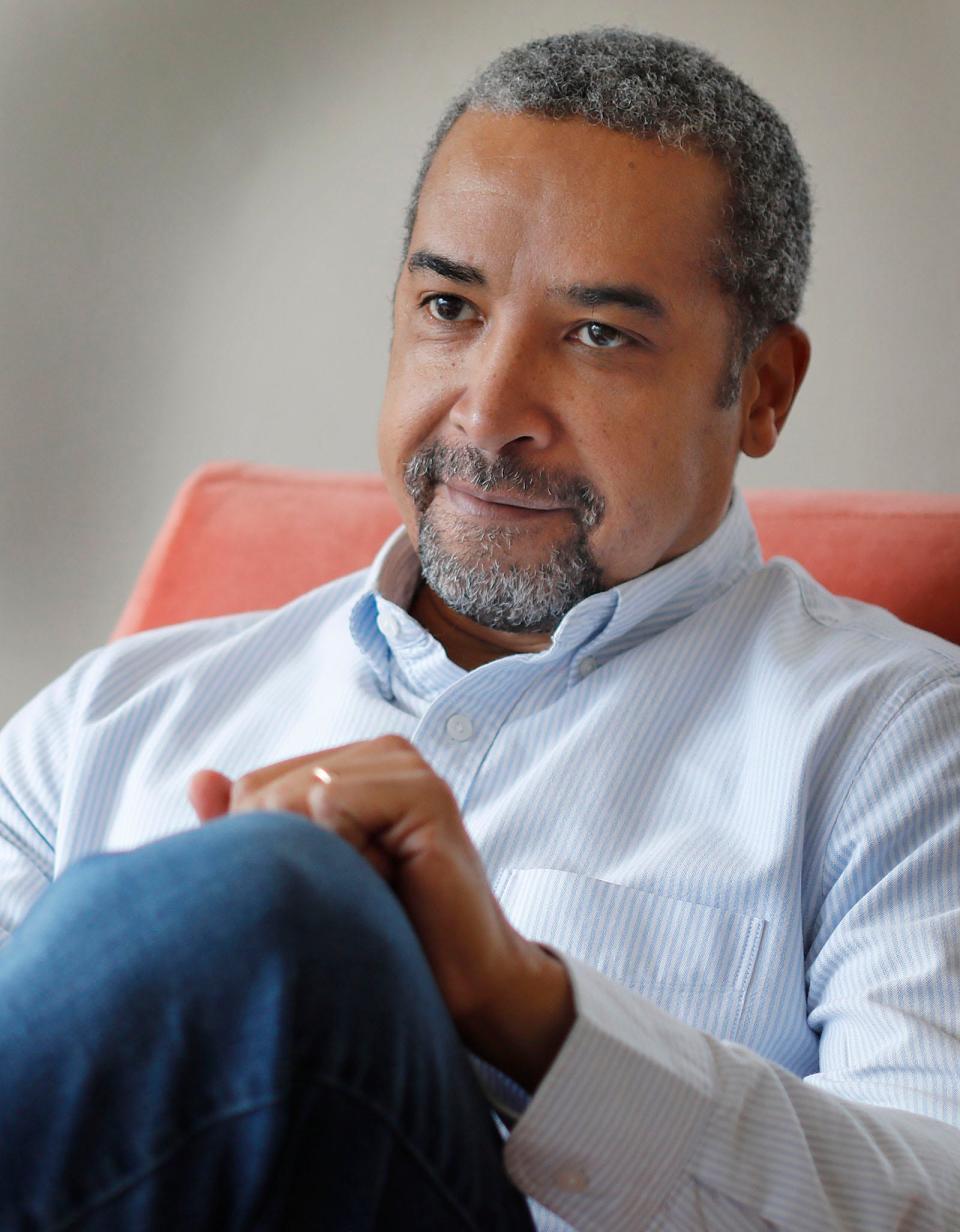

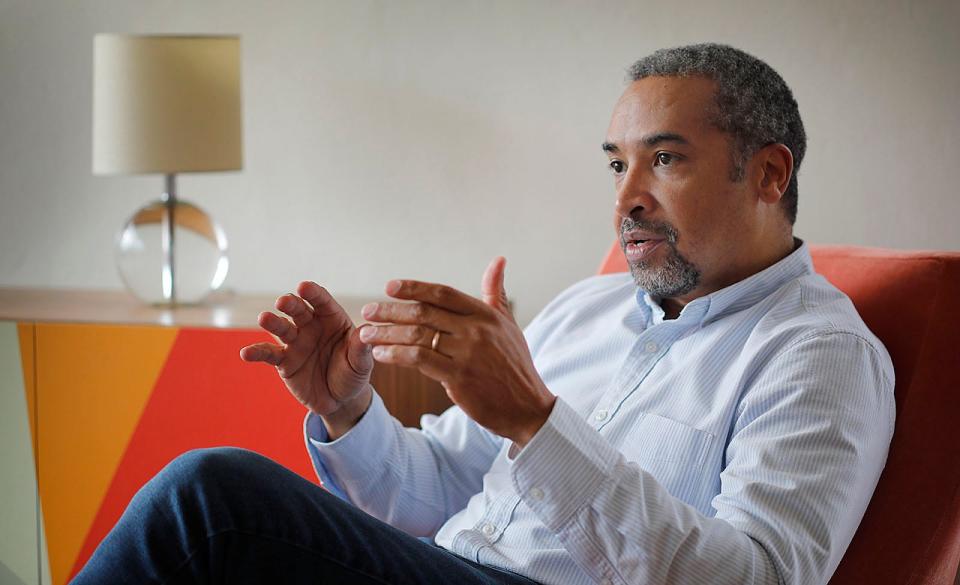

Hingham author Jerald Walker devoted more than a decade of his life to writing his latest book, "How to Make a Slave," but he has spent all 59 of his years living it.

Walker’s book is a collection of serious and humorous personal essays that includes reflections on his experiences in academia, such as racial profiling by a campus security guard, accounts of discussing race with his sons, Adrian, 22, and Dorian, 20, and contemplations on religion and even Michael Jackson.

"The stories are mainly about me, and I'm trying to give readers a sense of my values and philosophies," Walker said. "But they also necessarily have something to say about the racial dynamics in this country because I’m affected by it every time I leave my house."

"How to Make a Slave" was a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award for nonfiction, and its success helped Walker land a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship. He is a professor of creative writing at Emerson College in Boston, an Iowa Writers Workshop alumnus and a contributor to the Washington Post, The New York Times, Mother Jones, Harvard Review and The Oxford American. Walker won the 2021 Massachusetts Book Award, which he collected at the State House in January.

'Ant-Man 3':Jonathan Majors steals the show as villain Kang the Conqueror

Walker and his wife, Brenda Molife, have been married for 28 years. She is the provost and vice president of academic affairs at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Eight years ago, the family moved to Hingham, where Walker finished "How to Be a Slave," the book he spent 15 years writing. The book takes its title from Frederick Douglass’ famous line: "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man."

Next, Walker is penning another collection of essays, which will "be just like that one, only better," he says with a laugh. Walker recently sat down for an interview with The Patriot Ledger at his home, which is a Hugh Stubbins-designed mid-century modern style with floor-to-ceiling windows that make you feel like you’re outside. Natural light floods his office, illuminating the calming view of a marsh and woodlands. It’s a writer’s paradise where Walker spends the next hour talking about his work, growing up on the South Side of Chicago, and the challenges he faced on his path to success.

‘Oh no! We’re going back to the hood’

Walker said the South Side of Chicago provided him with a faith and values foundation he forgot he had until he returned as a father, husband and accomplished writer to celebrate his mother’s 80th birthday.

WALKER: I have one of the essays in the collection that’s called "Once More to the Ghetto," and it's about me, my wife, and our sons visiting family in Chicago after not being there for maybe a decade. My sons, who were raised in Massachusetts, heard the stories that people often hear about places like Chicago and the South Side of Chicago: that they’re dangerous, terrifying, scary places. It was kind of that way when I was growing up there, but it was also kind of not, because I was in that community and these were my family and friends, and so the whole stereotype of this being some complete war zone kind of escaped me while I was in it, and yet, being away from it for a while, I became susceptible to the stereotypes about the city as well. And so, with the notion of going back for my mother's 80th birthday, we were all a little worried, like, ‘Oh no! We’re going back to the hood.’ The closer we got to it, the more and more uptight my sons got, and the more and more I got worried about it, and upon arriving, I recalled that most of what I experienced growing up in that community was the humanity of my family and friends, the support from one another, and loving relationships. Yes, there were dangers and crimes; I had a best friend who was shot and murdered, and I had many guns put on me. So we went through all of that, but most of what I experienced in the heart of the ghetto were positive and affirmative and the kinds of things that make you cherish your community and your friends more than fear them and I had forgotten that for being away for so long.

Academy Awards 2023:15 shorts vying for Oscar gold headed to Plimoth Cinema

Living life like a gangster

Before he became a South Side success story, Walker said he dropped out of high school at age 16 and got involved with gangs, drugs and alcohol.

WALKER: One day when I was 20 years old, a friend of mine contacted me to say would you like some coke on credit, and you know I didn’t have any money and I said sure and so he said, 'Meet me at this apartment and I’ll get it to you,' and so, I went to the apartment and as I went through the alley to go up the back stairway, someone came out of the shadows and put a gun to my head. He patted my pockets, discovered I had no money, and I tried to leave. He said, "No, go where you were going." I went up the stairs and I saw my friend, and I said, "Hey, I just got robbed downstairs." We both laughed about it because that kind of thing was common. You make it through it, you make a joke out of it, and that’s that. I got the dope, went back downstairs, the guy wasn’t there, luckily. I went back to my apartment and I proceeded to get high. About 30 minutes later, I got a call from one of my brothers, who said, "Did you hear what happened to Greg? Greg is the guy I just got the dope from, and I said, "No, I just saw him 30 minutes ago" and he said, "He’s dead." I said, "What do you mean he’s dead?" He said they found his body in the alley at the bottom of the stairs, and he’d been shot six times. So the likelihood is that the guy who put the gun to my head and didn’t shoot probably put the gun to Greg’s head and did shoot. That was the night I decided I needed to make a change or that was going to be me someday soon beneath some stairs. I took the rest of the drugs and dumped them out my window, and I haven’t touched them since. It took me another two years to discover community colleges, so I got my GED and went to a community college. From there, I met a creative writing professor who said you ought to be a writer.

'I didn't want to be dead'

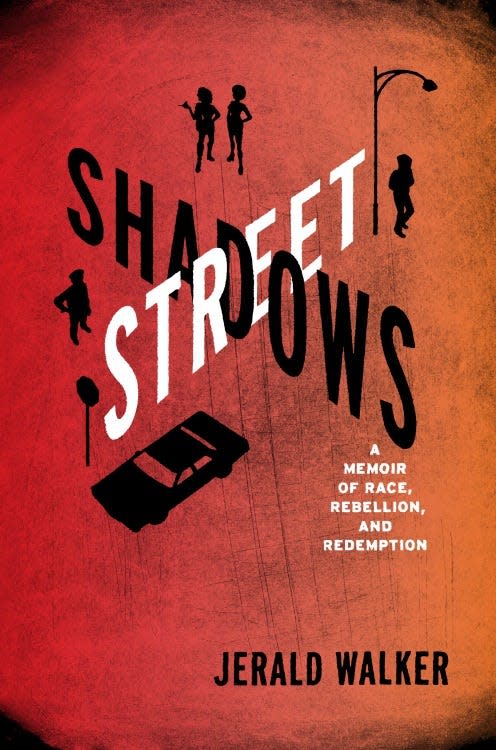

Until he was about 24 years old, Walker never considered a career in writing, never mind teaching. Now, he’s doing both. Walker's doctorate is in interdisciplinary studies, combining the fields of African American literature, African American history and creative writing. He published his acclaimed memoir, "Street Shadows," in 2010 and taught at MIT and the University of Iowa before landing at Emerson.

WALKER: I had no idea what I wanted to be. I just knew I didn’t want to be a gangster or a thug; I didn’t want to be dead. I knew school would be the solution. I just didn’t know what the subject matter would be. I toyed with the idea of being an architect because I like architecture, sociology and politics. I took courses in all those areas, and I failed them all. Not because they were too difficult but because I just didn’t have the interest in them. When I took a creative writing class, it was completely random. ... I wrote a short story, and the professor took me out to lunch the next day and said, "You’ve got talent; you should be a writer." I thought "OK," just because he said it, not because I had any desire to be a writer. What I needed was somebody to tell me I was good at something. If he’d said to me you ought to be a politician, I’d be the mayor of Boston right now. Whatever direction he pointed me in, I would have gone in it. He just happened to point me toward writing, and so that’s where I went because I didn’t know what to do myself.

Racism in restaurants

"How to Make a Slave" consists of 21 essays. Walker gives readers a glimpse into life as a Black man in America. In "Dragon Slayers," he recounts how he was racially profiled by an Emerson College security guard because he was guilty of being Black while walking through the lobby of a building, and says he was seated at bad tables in fancy restaurants.

WALKER: The story with the security guard at Emerson College is that I was on my way to a meeting when the security guard stopped me and asked for my identification. I refused to give it to her because I’m just not going to do it. I was clearly racially profiled. It was annoying in one sense, but it was also empowering in another because I was thinking, "That’s all you can do. You can ask for my ID, which I’m not going to give to you," because I’m in a position where she simply cannot hurt me... What’s discouraging about that is that there are many other people who could be hurt by her, but I knew my position at the college, I knew the rules, and I knew I was in no real danger from her. It's annoying to have to go through that, but it's also a good indicator of how far we’ve come and that we are in a position to fight back against those sorts of instances. The thing about restaurants is that when you get the bad tables, no one is going to say, "Mr. Walker, here’s your seat; it's for Black people, and it’s bad as you can see." You don’t know why it's happening, so you get frustrated by it and it can make you a little bit paranoid, but ultimately, unless someone comes out and says this is why this is happening, there’s not a whole lot you can do about it except choose to go to a different restaurant. ... Sometimes I wonder what people who aren’t writers do with this stuff because I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t have an outlet for it. When I was being confronted by that security guard, I was already thinking, "This is going to make a fantastic essay." I don’t go out looking for this stuff; I don’t want to have any encounters; I would rather have nothing to write about. ... When I sit at my computer every morning, it’s not because I’m trying to pay back some waiter who’s rude to me or write about something to make someone pay a price for mistreating me. It’s because I’m trying to win Guggenheim fellowships and other literary prizes and to make my mark with other writers of my generation.

Memories of Michael Jackson

In "How to Make a Slave," Walker considers a range of subjects, from bias in health care to blasting stereotypes to the complicated legacy of Michael Jackson and the late King of Pop’s influence on his life.

WALKER: When I was growing up on the South Side of Chicago, Michael Jackson’s family was just becoming one of the major musical groups in this country. And they resembled our family in the sense that their parents were very strict and religious, just like my parents. They were Jehovah’s Witnesses. We weren't, but we were in a religion that had similar beliefs and practices. Part of their belief structure was that they had to spend time with people of their faith specifically, and so they spent a lot of time with their family because there weren’t a lot of people running around Gary, Indiana, who were Jehovah’s Witnesses. So they spent a lot of time with their family, and so did my family. When they became embraced by culture and had television specials, we saw for the first time a family that looked like ours on television and that was accepted by this society, and that was pretty phenomenal, so they were role models for us. I certainly became obsessed with Michael Jackson and the Jackson Five, and I just wanted to emulate their belief in family and their excellence and use them as a way of saying to the broader society that we can be outstanding at something too.

On Netflix:Documentary 'Bill Russell: Legend' is a 'wonderful treasure trove'

Trapped in a cult: Losing our religion

Walker’s memoir "The World in Flames" recounts a period from his youth in the early 1970s when his family belonged to a religious cult. Subtitled "A Black Boyhood in a White Supremacist Doomsday Cult," the book was published in 2016.

WALKER: We had to fast. There were certain foods we couldn’t eat. We couldn’t celebrate birthdays, Christmas or Halloween. We went to church on Saturdays. It was a very strict religious upbringing. But it was, in fact, a cult. When we discovered that, I was 14 years old or so and it was kind of devastating to realize that you’d been duped into believing that all of these things which turned out to be kind of insane and that the leader of the cult was making money off of us, and so it was a very complicated, difficult upbringing, but at the early stages of it we saw ourselves in a righteous religion just like the Jacksons, so we felt a kinship with them.

Depicting Black people as heroes

Walker is also the author of "Street Shadows: A Memoir of Race, Rebellion, and Redemption," winner of the 2011 PEN New England Award for nonfiction. In his work and teaching, Walker shows Black people as heroes rather than victims.

WALKER: My philosophy is to focus more on the positives of Black life than the negatives, that we are not exclusively victims, we are not people to be pitied, we're people to be admired and celebrated and praised for all that we have achieved and overcome. The story of African Americans is a story of heroism, not defeat, and that’s what I try to focus on when I teach my literature courses, and that’s kind of the philosophy of the essays I write. I’m writing stories that allow people to see African Americans as I see them: courageous, heroic, strong and capable of confronting any obstacles that are brought our way.

Rejection and redemption

Walker received more than 20 rejections for "How to Make a Slave" before Ohio State University Press published it. The book went on to become a National Book Award finalist.

WALKER: Some of the difficulty when I made the decision to become a writer is that often people underestimate your talent and sometimes in publishing, publishers want Black writers to write stereotypical pieces and pieces that again feed into this line of us being victims and worthy of pity. ... I don’t write like that, so sometimes getting my work published was difficult. This book, in fact, had over 20 rejections before it was finally accepted somewhere. So that’s been one of the difficulties, is simply trying to make your own way as a writer and presenting your philosophy in world view, and if that’s in conflict with what publishers want, then you’re going to have a difficult time getting published.

Paying homage to his writing mentor, James Alan McPherson

Walker dedicates "How to Make a Slave" to James Alan McPherson, the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and his mentor at the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop. Walker said McPherson called him out for selling the stories of the ghetto for his own personal gain. It left a lasting impact on Walker and changed his worldview.

WALKER: He helped me see African Americans and our struggles in a positive light and recognize that we are more than the sum of our victimhood. That there’s humanity ... that we have managed to come out of the history of this country, out of slavery and reconstruction and Jim Crow and all of that to achieve what we’ve achieved is factually something positive and I was solely looking at Black life and Black experience in a negative light and so the effect that he had on me was to rethink my approach to how I viewed myself, my community and my philosophy of writing, and that’s why I dedicated that book to him.

'A lack of racial diversity' in Hingham

Walker moved to Hingham eight years ago, and in his book he recounts raising his two sons in a predominantly white suburb, an upbringing that was opposite of his own. He was born and raised in housing project. The 2020 census, which is the most recent data, reports Hingham as 93.9 percent white.

WALKER: It has been positive in some ways and in some ways negative. Positive, in the sense that it’s a safe community with outstanding schools, and that’s why we moved here. We wanted our boys to go to good, solid public schools, and you won’t find any that are better than the ones in Hingham. So in that respect, it's been great. On the downside, which is true not only of our kids but everybody’s kid who lives here, is that there’s a lack of racial diversity – that matters. It’s important, for people to be exposed to people of different cultures and different backgrounds, and they haven’t had a lot of that. They didn’t have a lot of that when they were here; they had more of it when they went to college.

Thanks to our subscribers, who help make this coverage possible. If you are not a subscriber, please consider supporting quality local journalism with a Patriot Ledger subscription. Here is our latest offer.

Reach Joel Barnes at jkbarnes@patriotledger.com.

This article originally appeared on The Patriot Ledger: Hingham's Jerald Walker reflects on Black life in How to Make a Slave