Historic achievements, 'beautiful lives': Paying tribute to Brevard's Black community

Some of these stories are well known. Others, deeply hidden.

The richness of Black history in Florida and Brevard is illustrated in these accounts.

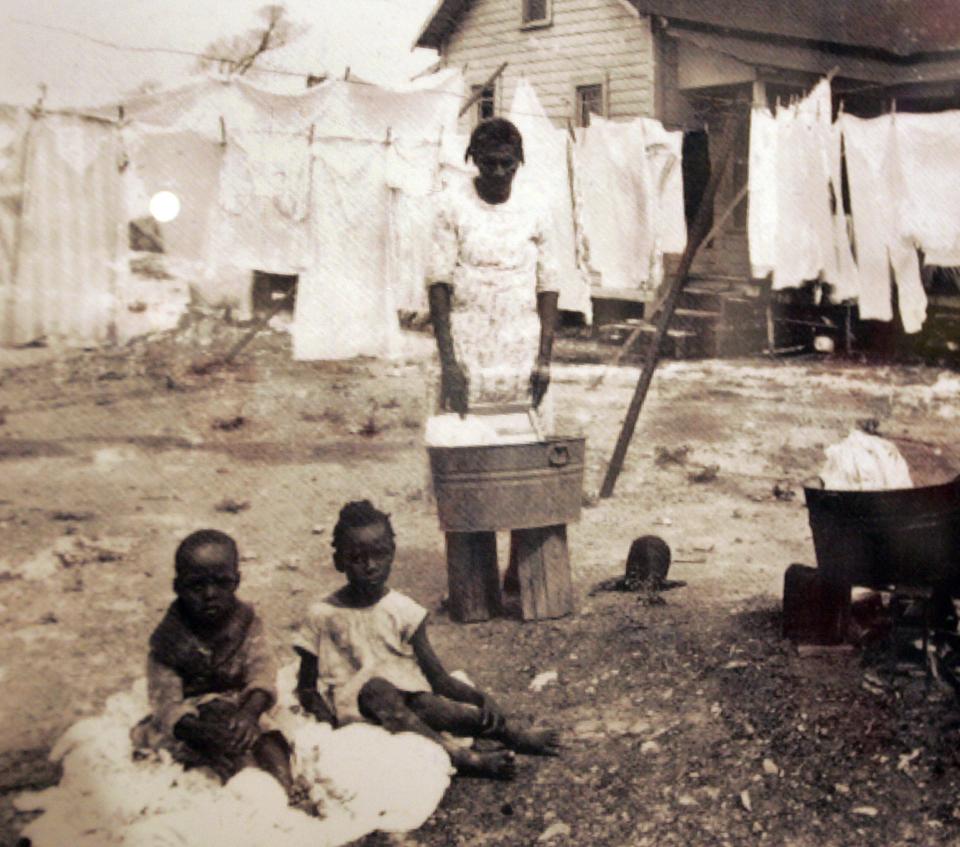

Stories of strength, of Black families rising despite struggles to forge a better future for those who'll follow in generations to come.

Stories of triumph and tragedy, of lynchings and massacres, haunting reminders of the darker chapters of the American story but also, of the resilience of the human spirit.

As Black History Month 2022 wraps up, join us at FLORIDA TODAY on this journey through successes and heartaches and, ultimately, the commitment to keep sharing these stories.

Nature gap: Black people strive to overcome history of recreational barriers, reconnect with Florida land

Juneteenth: Freedom. Joy. Jubilation. Juneteenth is an American celebration to its core

MLB legend: Hall of Fame nod long overdue for Buck O'Neil, a baseball legend and class act | Opinion

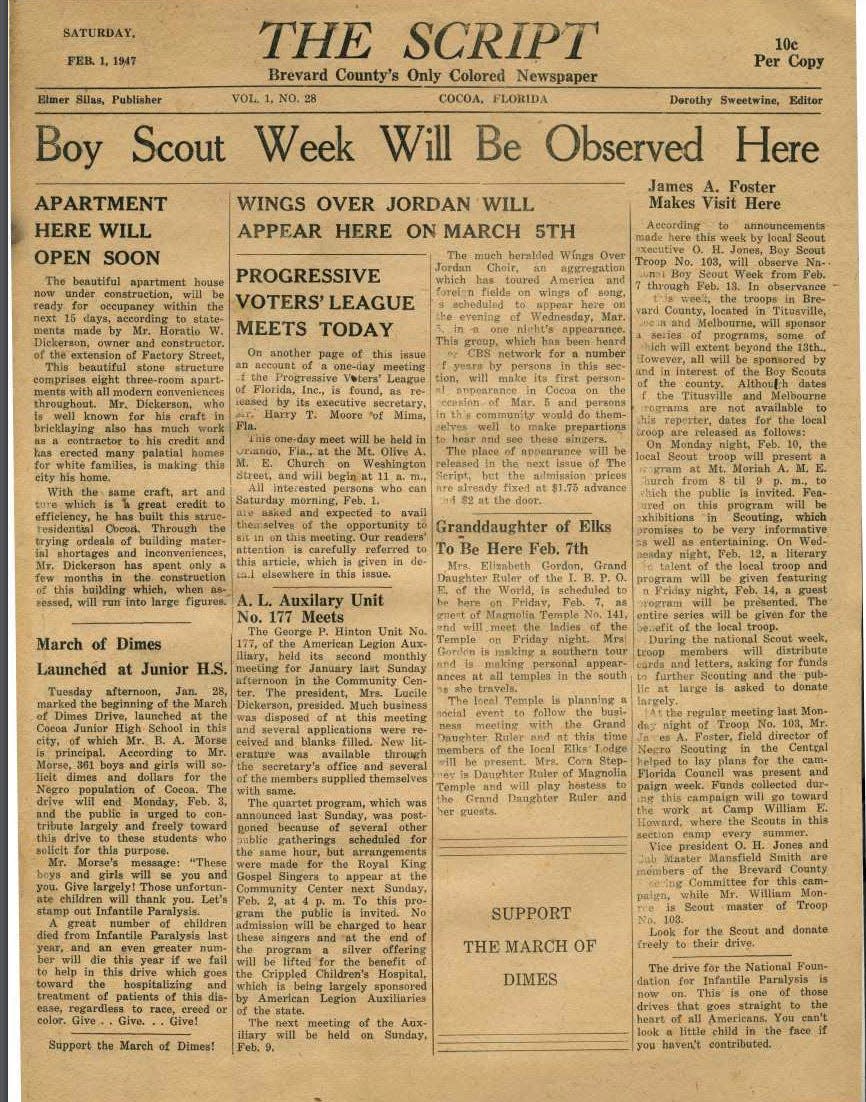

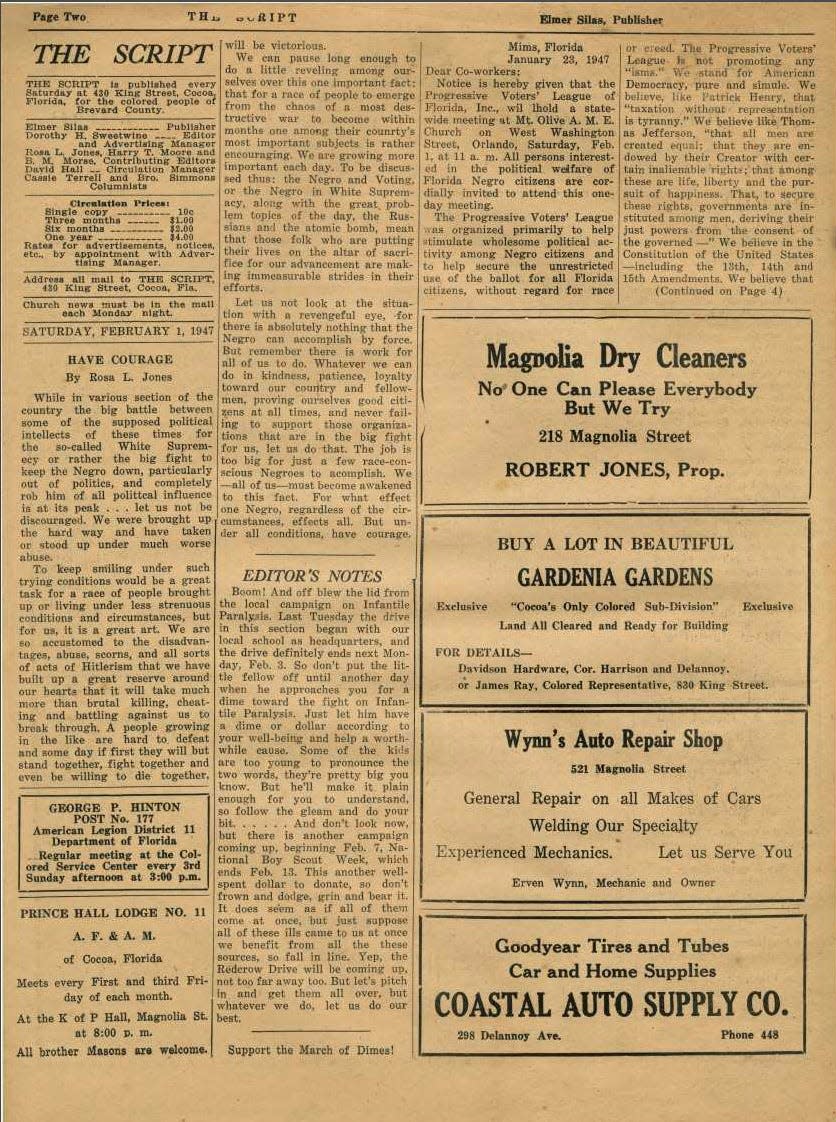

Family: Rosa L. Jones and Buck O'Neil

She was a civil rights activist, educator and journalist who has a street named for her and a mural dedicated to her in the city she loved and served.

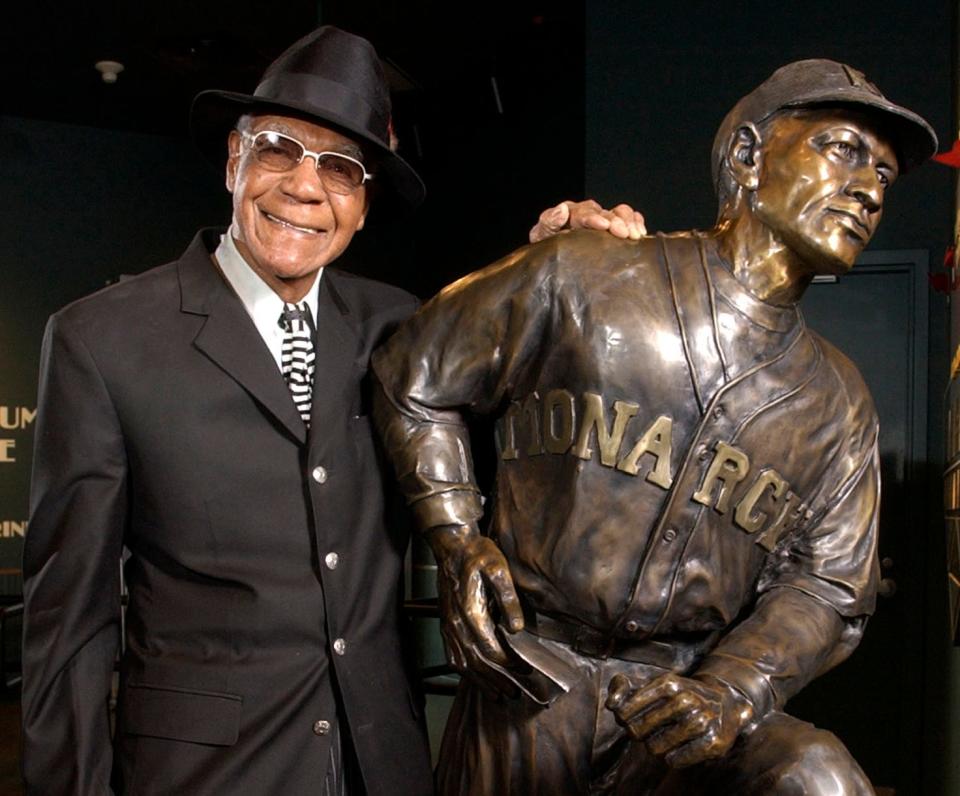

He was a star first baseman in Negro League Baseball, and will be inducted into the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., this summer.

She was the first Black daycare owner in Brevard County. He was the first Black coach in Major League Baseball.

Here's something, however, you might not already know about these two iconic Florida natives: Rosa Lee Jones and John Jordan "Buck" O'Neil were first cousins.

They weren't just kin who seldom saw each other. Jones also lived for a time with O'Neil and his family in Sarasota's Newtown community after her mother died when she was 4.

Both Jones and O'Neil were born in Carrabelle, Florida — Jones in 1907; O'Neil in 1911.

"When Rosa Lee lived with Buck and his family, it's said, she was the first person who threw a baseball to Buck while they played outdoors," said Rena Baker-Francis of Sacramento, California, Rosa Lee Jones' granddaughter and daughter of Rebecca Jones Baker of Cocoa.

Baker-Francis reflects on both her high-achieving relatives with pride.

Jones left home to pursue her education and "Buck went on with his baseball career," she said.

And what a career: as a Negro League player and manager for 18 years, one season leading the league with a .353 average. And as the Major League's first Black scout and coach, both jobs with the Chicago Cubs, before his return to Kansas.

The Sarasota Herald-Tribune reported in 2021 that "O’Neil became royalty of a sort in his adopted hometown of Kansas City, where he worked for the Kansas City Royals and helped found the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum."

Jones completed her education at FAMC High School (now FAMU) in 1922 and at Walker's Business School in Tampa before moving to Cocoa to work as a secretary for a white businessman.

"This is where she met her husband, my grandfather, the late Osborne Herman Jones, who was sent to pick her up from the train station in Cocoa ... and great history ensued," said Baker-Francis.

Jones' impact on Brevard County was influential and indelible. She was the first Black Girl Scout leader in Brevard and a civil rights pioneer who worked alongside Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore. A radio personality and journalist, she wrote for and edited The Script, billed as "Brevard County's Only Colored Newspaper." Generations of Black children in Cocoa, down to the current mayor, Michael Blake, were taught and cared for by Jones.

As far as relatives know, though O'Neil visited Jones in Cocoa a few times when they were adults, they weren't in close contact because of the divergence of their lives and careers.

But the entire family treasures photos of their famous kin, including one of the two cousins in their older years — O'Neil in a Kansas City Monarchs T-shirt.

O'Neil died at 94 in 2006. Jones died at 101 in 2008. Jones' legacy included many of her descendants becoming educators.

Rosa Lee Jones: Civil rights pioneer, educator to be honored with mural in Cocoa

A closer look: Rosa L. Jones Mural Dedication in Cocoa

"She opened doors for young Black kids to be afforded the opportunity to be educated and to learn during times when these demographics of people were left behind and not given a chance," said Baker-Francis, who earned an MBA and is an IT project manager for the state of California.

"She had a humble and gentle spirit — that is why she was so loved by everyone."

Saving final resting places

Oh, the stories a cemetery can tell — if the cemetery hasn't been lost to time and history.

With decades of race-based laws that marginalized Black communities, it's no surprise to historians that there are an estimated 3,000 "lost" Black cemeteries in Florida — 1,500 more than originally thought to exist by a task force on abandoned and neglected cemeteries formed at least two decades ago.

"So many of these forgotten burials have been identified, that the state of Florida in 2021 created a coalition of archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians to find and properly preserve these sites ... potentially hundreds of burials have been rediscovered in Florida, some covered with parking lots and apartment buildings," said Ben Brotemarkle, executive director of the Florida Historical Society.

The discoveries show that racism existed even to the grave.

"Even in graveyards and cemeteries from the late-19th century through the mid-20th century that have 'Black sections,' the markers identifying the burials of Black people were often made with less permanent materials, leaving the graves sometimes unmarked today," Brotemarkle said.

"Properly identifying and marking the burial sites of people who have been forgotten is important to preserving our shared history, and is also just basic human decency."

Sometimes, economic factors led to the graves of Black residents never being marked at all.

In many cases, abandonment, neglect and natural causes have led to destruction.

Some of the more well-known Black cemeteries in Brevard — and there are several — include Hilltop Cemetery at U.S. 1 and Peachtree Street in Cocoa.

Using eminent domain, the city of Cocoa, in 2000, took ownership of Hilltop, the burial place for many Black residents since 1877 that's known by many locals as "Cemetery Hill."

Time, and the elements, have visited there, too.

Back in 2001, during a cleanup of debris dumped onto Hilltop Cemetery by Tropical Storm Gabrielle, a crew from the Brevard County Sheriff's Office Farm found 58 graves that had been buried beneath a years-long accumulation of grass, dirt and debris. Until then, 417 graves were known to have existed at the site. In 2018, the decaying grave of Ella Sheffield (1904-1972) was discovered, with her coffin lying exposed. City officials dispatched Public Works employees to restore Sheffield's resting place.

Roz Foster of Titusville has devoted decades of her life to mapping cemeteries, uncovering and celebrating the lives of Brevard residents, including those laid to rest at previously unknown or abandoned Black cemeteries.

On Feb. 26, she and others from the Brevard County Historical Commission dedicated a marker at the Dennis Sawyer Memorial Park and Cemetery at Greater Mount Olive AME Church on Merritt Island.

There, the gravesites of Bahamian émigré Edwin Dennis Sawyer and his wife, Rebecca, were discovered.

According to historians, Sawyer worked on a ship and lived in Fort Pierce before moving to Cocoa, where he married Rebecca Dallas. He organized and helped build Mt. Olive AME Church in 1908. Land for a Black cemetery there was donated in 1956. Rebecca Sawyer died in 1960; her husband, in 1964.

A survey uncovered six other gravesites. One, marked “MI Bowman,” was for a 6-year-old child who died in 1962; only broken pieces of concrete remained for the other five.

"We were always taught as children to always respect people who who have passed," Foster said. "They have a great story to tell and what I found out through research ... my heavens. These people had beautiful stories, beautiful lives, and they were the foundations of the community. To neglect that, to not be able to tell their stories, would be a loss to humanity."

Rosewood: Preserving forgotten history

The first time Lizzie Brown Jenkins heard the story of Rosewood, she was 5 years old, sitting in front of the warm glow of a fireplace with her siblings.

But instead of a fuzzy children’s story on that otherwise cool evening in 1943, Jenkins heard the haunting retelling of an American nightmare from two decades before.

“My mother told us. I had no idea what the word massacre even meant. I remember drifting off to sleep,” said Jenkins, who shared her aunt's account and the story of Rosewood at the Florida Institute of Technology in 2020.

“The next day my mother was making biscuits but I wanted to know more, to know what happened to my aunt, my favorite aunt who made my clothes. This is here with me to share."

For more than 30 years, Jenkins, now 83, has worked to tell the horrifying story, one of murder, rape, and destruction that like other racially charged massacres - including the Ocoee Massacre in 1920 - were kept out of the nation’s history books.

It’s a story Jenkins, who founded the Real Rosewood Foundation Inc. in 2003, says must never be forgotten despite efforts underway to reshape how children are taught about race in America. The story was almost forgotten until survivors began to speak out in the 1980s to share what happened.

The predominantly Black community of Rosewood had nearly 400 people and was located near the timber-rich area of Cedar Key on Florida’s west coast. It was ransacked, looted and burned to the ground by a white mob for a week beginning Jan. 1, 1923, according to accounts.

Black History Month: Descendant of Rosewood massacre to speak on history, healing at FIT Read-In

Black history in Florida: Florida Frontiers: Florida's Black History

The racial violence — in which white mobs from surrounding communities flooded into Rosewood — officially claimed the lives of eight residents, although some historians have suggested as many as 200 people were killed.

Mobs — including Ku Klux Klansmen from Gainesville — converged on the town and suspected a resident of hiding an escapee from a chain gang. Then came the shootings and the fire.

White shopkeepers in Rosewood attempted to hide residents in their homes while others fled into the night, wading through cold damp swamps before climbing aboard an overnight train that whisked them to safety, according to multiple accounts.

Jenkins’ aunt, Mahulda "Gussie" Brown Carrier, who lived in the town, was gang-raped by the mob.

Carrier’s husband was beaten, then tied to a car and dragged along the road for three miles before the white sheriff intervened and took him to the safety of a jail cell where he would slowly recover.

Jenkins said people should not be afraid of history but allow both the good and bad to be told so that others may learn and avoid the same mistakes.

She is working to have the last standing building in Rosewood relocated for the creation of a national civil rights landmark that would include a non-profit library and history museum. A reconstruction of the town — similar to the reconstruction of the home where Harry and Harriette Moore were killed in Mims — would sit on 29 acres of land in Archer, Florida, not far from the original Rosewood location.

“You have to know whose shoulders you stand on,” Jenkins said. “We’re going to keep telling the story. It’s in God’s hands. We need truth and reconciliation.”

Telling the world

Across the state from where Rosewood once stood rests another testament to the days of Old Florida and another story of horror that history nearly forgot.

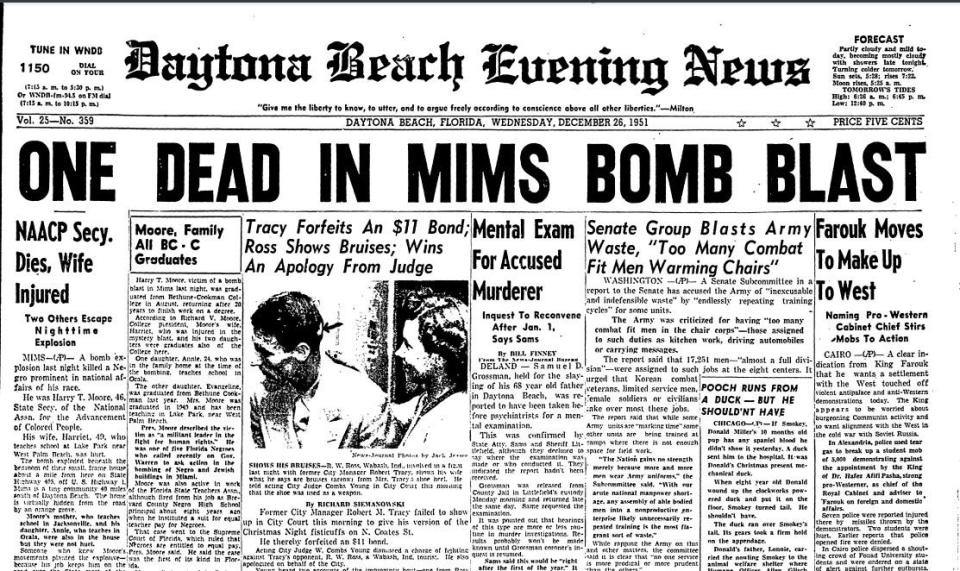

Here in the thicket of oaks and citrus groves of Mims on Christmas Day, 1951, was a modest home shared by Harry and Harriette Moore.

Both were educators and civil rights activists who traveled the state in the face of threats to register Blacks and to draw attention to cases like the Groveland Four in the decades following the Ocoee and Rosewood massacres.

'Contributions to our great nation': Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore posthumously nominated for Presidential Medal of Freedom

Their deeds were written about in the county’s only Black newspaper, where Rosa L. Jones, secretary for Brevard’s NAACP, wrote columns and where readers learned about the happenings across the nation.

On Christmas night, a bomb blast violently ripped apart the bedroom where the Moores — who earlier on Christmas Day celebrated their anniversary — had retired, shattering their bodies and generating headlines across the globe.

“It makes one sad to read the story of the bomb-killing of Harry T. Moore, the state coordinator for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People,” wrote former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a vocal proponent for civil rights and who had ties to Central Florida.

“That is the kind of violent incident that will be spread all over every country in the world and the harm it will do us among the people of the world is untold."

Despite the recognition, the couple’s story seemingly faded as the civil rights era marched on into a new phase with the ascension of Martin Luther King Jr. and the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi.

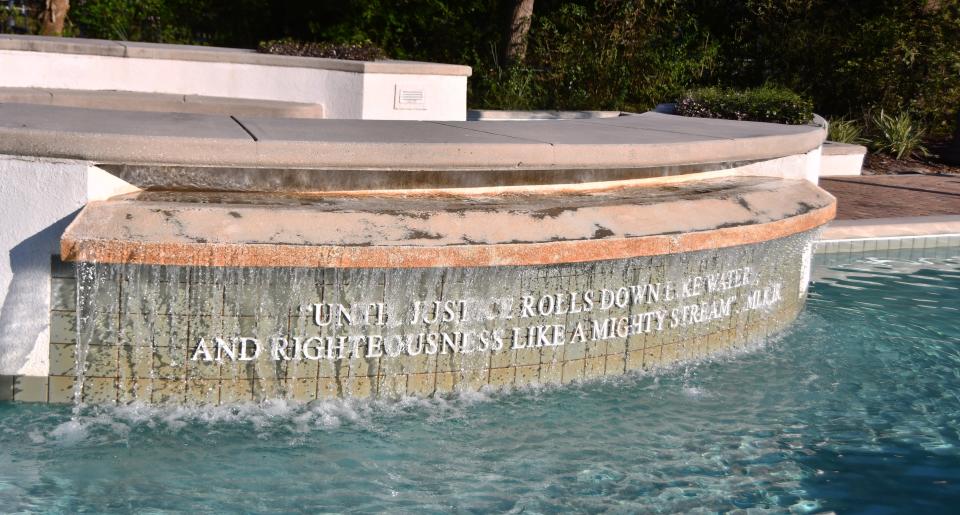

Seven decades later, however, the couple’s home has been reconstructed in a memorial setting with a reflecting pool, in a fashion not unlike what Robinson has in mind for Rosewood. The Moore Cultural Center Complex sits on the same property, welcoming children, tourists, and others who come to study one of the darkest chapters in Brevard history.

To Darren Pagan, a 30-year-old financial consultant living in the Washington, D.C. area, preserving the legacy of the Moores is a more personal investment. He is the great-grandson of the Moores.

“I was between 7 and 9 years old when I first heard about what happened to them,” Pagan told FLORIDA TODAY.

“I really couldn’t understand the magnitude until I got older. My grandmother (Evangeline Moore) allowed me to come up to speed about this naturally. But it really resonated with me as I hit my teen years. I understand that my grandmother’s parents sacrificed their lives,” Pagan said.

His grandmother would venture to Brevard several times as the story of what happened to the Moores saw a revival.

The Moores were transported 30 miles away to a hospital that treated Blacks in Sanford (closer hospitals only treated white people) — the same town that in 1947 saw Jackie Robinson integrate a minor league baseball game. It was also the same town that decades later would see a 17-year-old unarmed Trayvon Martin shot to death by George Zimmerman.

To Pagan, history’s brutal lessons offer critical insight not only into what happened in the past but what is happening now.

“You see the kind of wrongs that continue on the political side today, including voter suppression and police brutality and it’s like an unwillingness to acknowledge history or acknowledge that this is a thing,” Pagan said.

“It shows that we are still fighting ... .and it would be nice to continue to gain allies. To learn history, to learn about these stories."

This article originally appeared on Florida Today: Black History Month in Brevard showcases stories of strength, suffering