Historic Kentucky Christian school started to end family feuds still teaching 125 years on

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As James Anderson Burns told it, his idea to create what became Oneida Baptist Institute developed after someone cracked him over the head with the barrel of a rifle during a fight, leaving him for dead in some weeds.

That was in the steep-sided hills of Clay County in the late 1800s, when deadly violence was common between families and factions.

The knock on the skull didn’t kill Burns. When he woke, he went into the woods atop a mountain for three days, wondering how he had lived, he would later write in his 1928 autobiography, “The Crucible.”

Burns, the son of a Primitive Baptist preacher, experienced a religious conversion during his vigil, giving him “a heart of mercy instead of a heart of vengeance,” he wrote.

Burns became convinced that the way to end the feuds was to get the warring factions to cooperate in building a school where their children could be taught to not hate each other.

He laid the cornerstone for the first building in 1899. Oneida Baptist Institute (OBI) will turn 125 in 2024.

The school struggled financially at times and has gone through many changes in more than a century, but is on good financial footing today and hoping to expand, according to the current president, Larry Gritton Jr.

Ask him how OBI has lasted this long, and Gritton has a ready answer.

“It’s the Lord’s provision,” he said.

Joining the fighting

Burns’ father, Hugh, was from Clay County but left for West Virginia to escape the local hostilities among families, Burns said.

Burns said he heard his parents talk about Clay County and developed a curiosity to go. His father tried to dissuade him, but Burns went after his father died.

His uncle took him to a hillside cemetery and showed him graves of relatives who had been killed in the violence, describing the battles in vivid detail.

Burns later said his reaction was foolish, but at the time, the tales were “the call of the wild for me.” He joined the fighting, he said, “determined to avenge the blood of my relatives who slept in those untimely graves.”

Burns said it was a few years later when he got “lammed” on the head and came to understand that the Holy Spirit had changed his heart.

He told his brother he planned to try to end the animosity through Christian education.

‘Testing time of faith’

In 1899, Burns said, he and a Baptist minister from Kansas, H.L. McMurray, spent several weeks riding through the hills asking men from the opposing Baker and Howard families to come to a meeting.

They met at an old mill, 50 or so men total, staring at each other from opposite sides of the room. It was tense, and a wrong move “would have precipitated a terrible battle,” Burns wrote.

Burns said he told the men he knew they wanted to end the fighting, but they were doing it by trying to kill off the other side and teaching their children to hate in the process. He explained his idea to have them work together to build a school.

“Let’s teach our children to love each other and then we will have peace,” Burns said he told the men.

A man who had been at odds with Burns’ family strode to the center of the room and said, “Boys, let’s do that if it’s the last act of our lives,” Burns wrote.

Education had been so scarce in the area that most of the 12 men chosen as trustees couldn’t sign their names.

They chose Burns as president. He didn’t have a dollar and no source of income to start building, Burns wrote later.

“It was the testing time of faith,” he said.

It wasn’t just the Hatfields & McCoys. Why was 1800s Kentucky full of ‘feud’ violence?

The first building

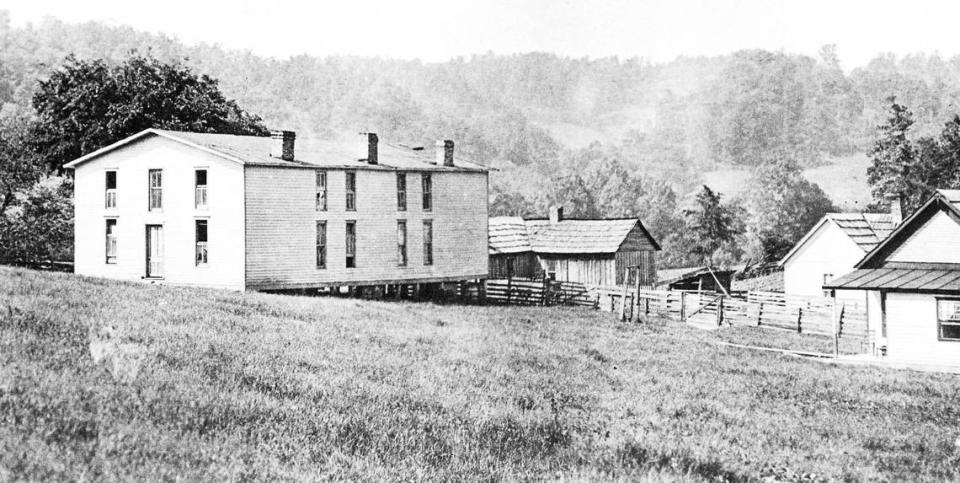

Burns and McMurray planned construction of the first building on a hill overlooking where Bull Skin Creek, Goose Creek and the Red Bird River came together into the South Fork of the Kentucky River.

Big Henry Hensley, a local man, made the first donation of $50. The school received other small donations, and men from the community brought materials and helped work on the first building.

The plan was to open on Jan. 1, 1900, but Anderson ran out of lumber at Christmas and the mill the crew had been using was broken.

When it seemed the school wouldn’t be done on time, a man from the community came up through the snow driving a team of oxen pulling a load of yellow poplar planks, enough to finish construction, Burns said.

The school opened as planned.

‘Lead them to love’

Burns — who had less than two years of formal education but learned to read at home and was intelligent — and two other men were the only teachers at first.

There were about 100 students in eight grades, with grown men learning alongside children.

“Our task was to lead them to love each other and while doing so, to teach them as much grammar and arithmetic as we could,” Burns wrote.

Tuition was $1 a month, but most students couldn’t pay. Students brought coal or garden produce as payment; one brought a sheepskin, and the teachers cut it into pieces to use as erasers.

Many students boarded with families in the area, which was relatively isolated at the time. The nearest railroad was 40 miles away, Burns said, and roads generally were in poor shape.

Burns said he and other teachers worked into the night to study so that they could begin offering high school classes, sometimes reading by the light of a fire on the creek bank as they fished for food for the next day.

“We never knew the source from which the next day’s rations would come,” Burns said.

Donations continued to trickle in, though. Broadway Baptist Church in Louisville, for instance, pledged $70 a month to the school.

The school had to turn away students because of a lack of places for them to stay and work for them to do.

Burns told the story of an old man and three girls who rode 40 miles in the winter of 1905 so the girls could go to school, only to leave in tears because there was not place for them to stay.

Burns determined to build a girls’ dormitory, hiring a man to do the work at a cost of $10,000 before he had the money in hand.

As the school grew, Burns concentrated on fundraising, touring the country incessantly for years to talk with church groups and others about OBI’s story and seek donations.

‘Freed from the feud spirit’

There were times in the early 1920s when the president and teachers went without salaries for lack of money, according to “Mountain Rising,” a 1986 history by Darrell C. Richardson.

In the fall of 1921, trustees discovered the school was deep in debt. The financial crunch happened because of a drop in giving in World War I and an “unfortunate administration” that Burns didn’t explain further in his memoir.

It wasn’t clear the school could continue, but after trustees hired the first, and so far only, female president, Sylvia Russell, she straightened out the finances, paying some of the debt herself, Burns said.

The school didn’t end all the violence in Clay County.

But Burns described an incident in the 1920s in which two men had traded gunshots in town — killing a mule but no people — as evidence that it had worked.

At one time the confrontation likely would have spiraled, but instead, after he talked to the men, they shook hands and left and the hostilities didn’t spread, Burns said.

“I have lived to see our mountain children emancipated from the bondage of illiteracy and freed from the blight of the feud spirit,” Burns said in his autobiography.

Burns lived out his final years on campus, an invalid after years of struggle to keep the school open. He died in September 1945 at age 80.

Returning to its roots

The school has gone through various iterations in its history, but in the last decade has refocused on its original mission of serving students from the area, Gritton said.

Gritton, a graduate whose parents taught at the school, is the 12th president in 125 years.

OBI hadn’t run buses to pick up students for many years, but resumed bus transportation so more local students could attend. It also hadn’t had grades kindergarten through 5 since the 1950s, but reestablished those grades eight years ago and reached out to the community to bring in students, Gritton said.

Most of the students are from Clay County, though some come from neighboring Owsley and Leslie counties.

Gritton said in a recent post in Kentucky Today that the school has 97 students in grades kindergarten through 5; 55 students in grades 6 through 8; and 83 high school students.

Enrollment this year is up 16% over last year, said Joe Scull, the principal.

The school also has continued is historic role as a boarding school. About half the high school students live in the school’s dorms, most of them international students.

The international boarding students pay tuition, but it doesn’t cover the full cost of their education, housing and meals, Gritton said.

Scull said one motivation for international students coming to Oneida Baptist is to learn English. Some come to get a leg up on entry to a U.S. college, and some are getting out of bad situations in their home country, Scull said.

Shiloh Tive, a 17-year-old senior from Nigeria, heard about OBI from a family friend and thought it looked like a beautiful place when he went online to see it.

“It’s a good school, a brilliant school,” said Tive, who wants to study finance at a U.S. university.

For non-boarding students, there is no cost to attend Oneida Baptist.

Gritton said parents choose to send their children to OBI for various reasons, including convenience, a belief their kids will get a better education and more specialized attention in smaller classes, or opportunities in sports or other programs.

The student-teacher ratio is about 15 or 16 to one, Scull said.

The school has a no-cut policy in sports, so everyone gets to participate.

“There’s two things I think draw people here — our people and our programs,” Gritton said. “Love and care for our students, that’s the best thing we do.”

‘You gotta love’

Some parents also want religious instruction alongside academic instruction for their kids.

Students don’t have to be Christian to attend, but the school is clearly a Christian institution, with required attendance at chapel services each school day.

“Everything is Bible-centered,” said Scull, the principal. “We infuse the Bible in every subject.”

Scull said OBI students receive a good education, though he wants to boost test scores.

“I want to be more rigorous moving forward,” Scull said.

One of the most notable former OBI boarders is Jen-Hsun “Jensen” Huang, founder and head of NVIDIA, a multinational technology company.

Huang’s father sent him and his brother to live at OBI when Huang was nine years old. His family later moved to Oregon and he finished high school there.

Huang donated $2 million to OBI for a dorm and classroom building.

Former Kentucky Gov. Bert T. Combs also was a student at one time.

The school receives money from the Kentucky Baptist Convention through the Cooperative Program — distributing money donated through churches around the state — but donations from individuals are still the most important source of funding, Gritton said.

“Oneida truly operates on the $20, $50, $100 donation,” he said.

Donations from Kentucky Baptists make up the majority of the school’s funding. It receives no state or federal funding in its $4 million budget.

The school still operates a farm where students work, and boarding students also work on campus. The school has cattle and grows produce used in the dining hall.

The starting salary for a teacher is $12,500. They also receive free housing, meals and utilities, so the value is higher.

But teachers aren’t at the school for the paycheck. They see their work as mission work, Scull said.

“You gotta love kids and you gotta love missions,” he said.

Gritton said the goal is to continue increasing enrollment at the school, He would like to see it reach 350 to 400 students.

Gritton said Oneida remains as relevant as it was 125 years ago despite the availability of public education that didn’t exist at the time.

The initial problem — deadly violence between local factions — is no more, but students face other challenges these days, including poverty and families torn my drug abuse, he said.

“We were planted here in 1900 because of a war,” Gritton said. “There’s a war today.”