Historically Speaking: Life and legacy of Benjamin Swasey, Exeter’s unsung history writer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

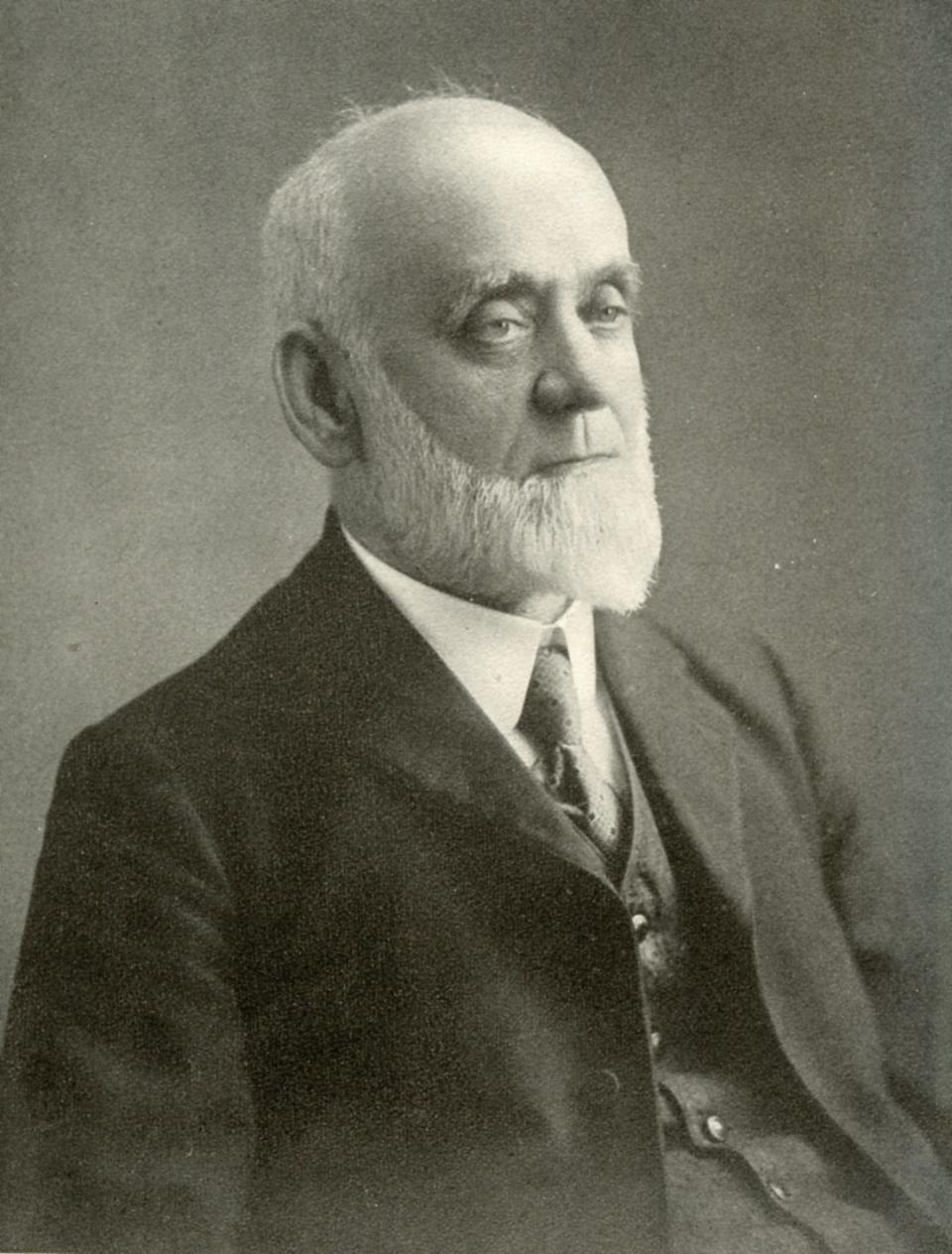

Of the dozen or so history writers of Exeter, Benjamin Franklin Swasey is probably the least known or cited. It’s a shame because his writing is filled with delightful tidbits not generally found in most historical works.

Benjamin Swasey was born in Exeter in 1837 and, except for only a few years, lived his life in town. Swasey grew up on his father’s farm on the west side of the Squamscott River. One of five surviving children, his most notable sibling was his younger brother, Ambrose Swasey, who is known for his generous gifts to the town (the Swasey Pavilion and Swasey Parkway). Swasey wrote of his father, “he was a great reader of ancient history and of the standard works on astronomy. He took much interest in the affairs of his native town and was elected on the Board of Selectmen in 1847-48.” In a period when a great deal of civic life included passing around the rum jug, Nathaniel Swasey refused to partake.

Benjamin attended local schools before entering Phillips Exeter Academy in 1852 at age 15. From there, he studied at Brown. His first choice for an occupation was teaching. Returning to town after his education was complete, he taught at the Kingston Road school. He later taught schools in Rochester and Strafford, followed by Limerick, Maine before spending five years in Macon, Illinois.

Returning east, he changed course and became a newspaperman – at the Exeter Gazette and the Haverhill Bulletin. He also found the time to write a history of the Baptist Church in Exeter and the Swasey family genealogy.

Historically Speaking: The rise and fall of Exeter Footwear

From 1907 until just before his death in 1914, Swasey wrote a series of articles for the Exeter News-Letter called Notes on Early Exeter. They are mostly filled with genealogy and land ownership, but within those confines, he inserts the tidbits of history that can be absolutely gold to later researchers. Some of his tales are things he heard as a boy. “A gentleman, now passed away, who lived to the age of 90 years,” he wrote, “used to say he had lived twice the number of years his age indicated. Upon being questioned to explain, he said: ‘My memory runs over the whole period of my life, and the information I gathered from my father and mother and from my grandparents is so lucid and clear in my memory that I feel I have lived contemporary with them.’” Swasey must have felt a kinship with that old man’s memory. He wrote about old burying grounds and pondered the location of Exeter’s first meetinghouse.

As he drafted his pieces, he often inserted reminiscences of the people who lived on the adjoining lands – people who were not necessarily the founding fathers of Exeter. From Swasey, we often get some of our best knowledge of Exeter’s early Black population. “I well remember the Mainjoy family,” he inserted while writing about the Green Street cemetery, “The father was brought to this country from Africa, a slave, by one of the Emery family. The children were Abbie, Henry, Mary, John, and Charles, who I am told is the only surviving child, a barber in Chelsea, Mass. A granddaughter, a graduate at Robinson Seminary in 1879, married Rev. W.C. Jason, a minister and president of the State College at Dover, Delaware.”

Historically Speaking: How Exeter experienced the roaring twenties in 1923

Swasey’s frequent reminders that Black people lived in Exeter – and often thrived – belied the common belief that Exeter was always exclusively white. “Mrs. Husoe may be well remembered by many families in Exeter as a kindly old lady whose services in their household were always appreciated. At leisure time, in the fall of the year, she could periodically be seen picking barberries in the pastures of which years ago there was an abundance. They had eight children.”

His offerings include stories about women in town, whereas Charles Bell (a more formal history writer) rarely mentions women except to say they were dutiful wives and mothers. Of Deborah Dutch, a spinster woman who owned her own home through inheritance and purchase, he wrote, “She had many characteristics in common with people now-a-days. She was not a ‘survival of the fittest,’ which is not always an indication that the fittest in every sense always survive. She knew just the exact way to bring up children, how they should be clothed, how fed, and how educated, and was a great help to mothers who were in the business. She knew what best methods to adopt in the management of a household and how to deal with an unruly husband. Church fairs and church sociable were her delight, in which she always held an official position and, knowing the dignity attached to it, she could exercise a good degree of authority. Of this class of personages, nothing can be said in their disfavor. They are cheerful, hopeful, and their hope never wanes, down to advancing years.”

Deborah Dutch died in 1848, after admitting to the deacon that she could not recall exactly when she’d been born (she was 77). Swasey was 11 at the time of her death, yet he remembered her clearly as an old man.

Trying to track down Exeter’s built landscape can be quite difficult. For time periods before photographs, we must depend on the town’s maps – which often leave decades undocumented. Swasey helpfully fills in these details. The Hutchins tavern was located where the post office stands today. The place was sold several times after its first appearance on the 1802 Phineas Merrill map. Swasey tells us that for a while – before 1826 – Benjamin Leavitt owned it. Leavitt had a large family comprised of four daughters and four sons. The daughters were frequently placed in charge of the tavern.

“It is related that on one occasion under this management the Leavitt girls put their heads together to play a joke upon the company gathered there, which generally consisted of the Odlins, the Gilmans, the Folsoms and others. They carried the joke out successfully by cutting up bits of flannel of different colors and inserting them into skins for sausages and frying them, which to all appearances were the real article. When the food was served for the table and the guests seated, the sausages were passed around with other viands. Quite soon there was a smile on the face of Capt. Nathaniel Gilman, whose knife refused to sever his portion of the sausage whose different colors came into view. Quietly and silently, he watched the other guests when they, too, soberly scanned each other’s faces, when suddenly a roar of laughter burst forth from all present, and the meal was finished with a due appreciation of the skill of the landlord’s daughters.”

Most of the history we read tends to linger with desert dryness. Benjamin Franklin Swasey managed, somehow, to continually write a balance of verifiable facts along with clever and entertaining vignettes of earlier days.

Barbara Rimkunas is the curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Support the Exeter Historical Society by becoming a member. Join online at: www.exeterhistory.org.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Historically Speaking: The history of Benjamin Franklin Swasey