History: After a century of effort, Joshua trees still in need of protection

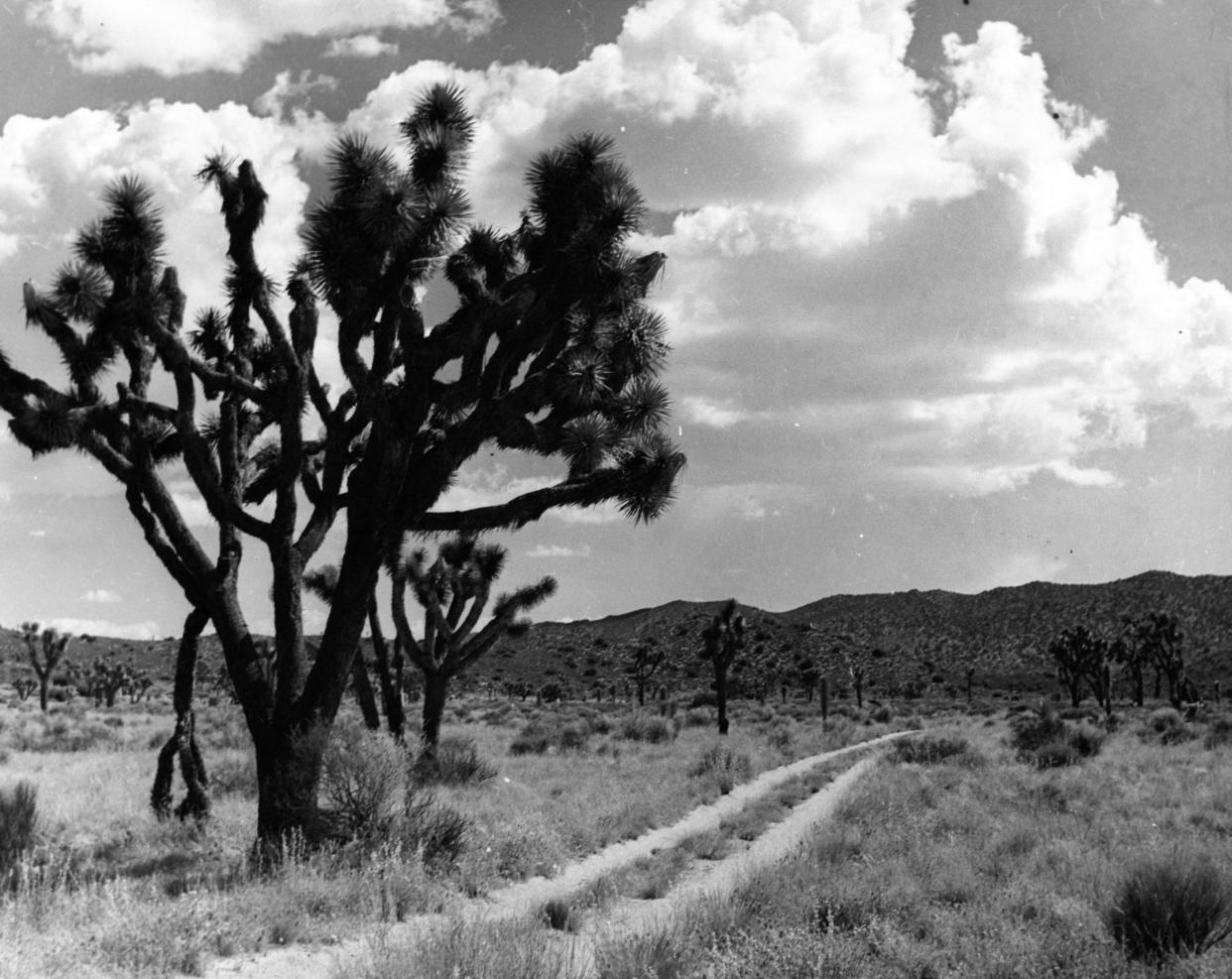

Strangely splendid, the Joshua tree of the Mojave Desert captivated Minerva Hamilton Hoyt. A wealthy Southern belle and Pasadena socialite, Hoyt’s desert trip in the late 1890s consumed her imagination. The landscape seemed surreal, as if transplanted from another planet. The desert, and specifically Joshua trees, would define much of her life ever after.

In an appeal to conservationists in 1929, the Los Angeles Times quoted Hoyt: “Over thirty years ago I spent my first night in the Mojave desert of California and was entranced by the magnificence of the Joshua grove in which we were camping and which was thickly sown with desert juniper and many rare forms of desert plant life. A month ago ... I visited the same spot again,” she continued. “Imagine the surprise and the shock of finding a barren acreage with scarcely a Joshua tree left standing and the whole face of the landscape a desolate waste, denuded of its growth for commercialism.”

Hoyt systematically set about protecting the rest of the beloved desert from the same fate. She consciously cultivated respect for desert plants through a series of extravagant desert displays in Boston, New York and London. The Los Angeles Times characterized the shows as incredibly lavish, noting that Hoyt filled seven freight cars with desert rocks, plants and sand and shipped it all back East. She flew in desert flowers twice a day, storing them in her hotel bathtub before installation.

The Associated Press reported that her London exhibition was so popular that a policeman had to be stationed in front of the cacti and stuffed coyotes to “keep the folks from crowding too hard against the ropes.” The Garden Club was impressed, as was the general public. Hoyt had succeeded spectacularly in raising awareness of the wonders of the desert.

The landscape and gardens of Southern California a century ago were something special. The irrigated desert was a veritable Garden of Eden, as every imaginable cultivar grew with ease. Strange and wonderful new specimens, exuberant in form and color, unknown in Eastern gardens, were abundant.

Landscaping in early 20th century Los Angeles with desert plants, particularly cacti, was highly fashionable. In search of specimens, gardeners and landscapers routinely drove from Los Angeles to the Coachella Valley to harvest yuccas, barrel cactus, cholla and anything else they could dig up. At the west end of the Coachella Valley, the Devil’s Garden, a dense stand of barrel cacti, made for a natural nursery and was decimated. During the spring of 1932 so many motorists came to pick desert verbena from the sand dunes north of Palm Springs, the sheriff posted men on the weekends to prevent the poaching.

The pillage was alarming and created a conservation effort and several ordinances preventing transport of desert plants on county highways were passed, but this did little to stop the devastation until Hoyt joined the effort.

Hoyt was duly considered a desert expert; a species of cactus was named in her honor; when the California State Park Associated hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., whose famous father had designed all the major municipal parks in the country, including New York’s Central Park, to survey the state for its important horticultural geography, he enlisted her help.

Hoyt selected one million acres extending from the Salton Sea to Twentynine Palms, recommending preservation and advocating for National Park status. Hoyt founded the International Desert Conservation League in March of 1930 and installed powerful and connected men — museum directors, university presidents, and the founder of the Forest Service — as vice presidents. She cultivated the agriculture secretary and other Washington officials, constantly pressing for preservation. Thwarted by a park service bureaucrat after a protracted effort and then all-out battle, Hoyt decided to go over his head directly to the president.

She procured a letter of introduction from California Governor James Rolph Jr. (for whom there is a street named in Palm Springs). She commissioned a slew of gorgeous landscape photographs from Stephen Willard and assembled the letter and the images into a glorious picture book, arranging for it to be presented to President Franklin Roosevelt himself by her friend Henry Harriman, president of the chamber of commerce of the United States. Delivered in summer of 1934, the album was persuasive.

Harriman reported the president’s great appreciation and interest in Hoyt’s work. Roosevelt was astonished by the images. In 1936, he signed a Presidential Proclamation establishing Joshua Tree National Monument as a mechanism for conserving desert plants. Decades later, Joshua Tree was finally designated a National Park in 1994.

Sadly, the urgent need to protect the strange and wonderful Joshua trees has not abated with the establishment of the park.

Writing in the Joshua Tree Voice, Chris Clarke has chronicled a new threat to the species. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) recently released a report claiming that Joshua trees are not in need of protection from the effects of climate change. In the spirit of Hoyt herself, Clarke, as well as Joshua Tree resident Brendan Cummings, have taken up the cause. Cummings filed a petition to protect the western species of Joshua trees under the State of California’s version of the federal Endangered Species Act.

The trees grow in the National Park and unprotected portions of Los Angeles County through the western Mojave Desert to Death Valley National Park. According to Clarke, “They rely on cooler, wetter winters in order to reproduce — to flower, set seed and have those seeds germinate and grow into sturdy little seedlings — and while the southern end of the Mojave Desert used to get strings of three or four such winters in a row back in the 1950s, they are now a thing of the past.”

Clarke notes this means “along with increasing wildfires, drought that causes wild animals to gnaw the trees’ bark off in search for water, and the insatiable appetites of developers for more desert land to bulldoze, the Joshua trees ... are in deep trouble ...”

Indeed, housing development, once thought unimaginable for the desolate high desert, is booming and plowing trees under in pursuit of profit.

The fate of the western Joshua tree will be determined by the California Fish and Game Commission on June 15, when it will decide whether to accept the CDFW’s suggestion or to grant the trees permanent protection.

A century ago, Minerva Hamilton Hoyt rescued the Joshua tree and the desert she loved from certain destruction. Those who still understand and appreciate the wild desert are again needed by the voiceless trees. Concern may be registered at fgc@fgc.ca.gov or through the action alert on the website of the Center for Biological Diversity, biologicaldiversity.org in advance of the June 15 decision.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Palm Springs history: Joshua trees still in need of protection