History: Desert Congressman Dalip Saund was democracy in practice

Geographically, California’s 29th congressional district created after the 1940 Census was huge — larger “than Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Delaware combined,” according to The New York Times — and unusually far-flung, bordered by Nevada to the east, Mexico to the south and Los Angeles to the west. But by California population standards it was small with only 233,021 people in 1950 and 378,296 in 1960.

The district had consistently elected a Republican to office from its inception. In 1955 when the incumbent John Phillips announced his retirement, the seat was fiercely contested by two Democrats and four Republicans in advance of the 1956 election, the eventual winner would be the first person of Asian descent ever elected to the United States Congress.

Dalip Singh Saund was born in 1899 in the Punjab, India, which at the time was still a British colony. While at university, Saund supported the movement for an independent India led by Mohandas Gandhi, learning about non-violent civil disobedience and beginning a lifelong interest in politics. Saund majored in mathematics and graduated in 1919. He made his way to America to further his studies. During this time he read the speeches of Abraham Lincoln, later writing that the words “changed the course of my entire life.”

He enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley in mathematics and agriculture in 1920, earning his Ph.D. in 1924. He moved south to the Imperial Valley, later remembering that “outside of the university atmosphere it was made quite evident that people from Asia — Japanese, Chinese and Hindus — were not wanted.”

He'd intended to learn about agriculture and return home to India, but according to his congressional biography, he found himself working as a “foreman of a cotton-picking gang at a ranch belonging to some Indian friends” in the desert. He saved money and quickly went into the business of growing lettuce and suffered financial disaster. He married and settled a few miles south of the Salton Sea, growing alfalfa for baled hay. Soon he owned his farming equipment but was precluded from owning or leasing land by California law due to his Indian descent.

During the Depression he refused to declare bankruptcy, working his way out of debt slowly.

After 20 years of desert farming with a Ph.D. in mathematics, Saund also owned his own fertilizer business and was commuting 1,000 miles per week between Los Angeles, where his wife and children were settled, and his business in the Imperial Valley.

He closely followed politics and was grateful for the help given farmers by the New Deal. He wrote in his memoir: “I had positively and definitely become a Democrat by outlook and conviction.” He worked in local politics, eventually winning a judgeship after a campaign that featured horrific bigotry. Throughout he adamantly refused to attack his adversaries, saying simply, “I am not running against anybody; all I’m asking for is a job, and it’s up to you to judge whether I deserve your support or not.”

In 1955 he resolved to campaign for the open congressional seat in the 29th California. He knew almost everyone in the eastern Coachella and Imperial valleys. He worried about Riverside.

Saund’s opponent in the Democratic primary was Riverside lawyer Carl Kegley. The race began cordially. Then Kegley asked the California Supreme Court to disqualify Saund, arguing Saund had not been a U.S. citizen long enough to serve in the House, making headlines with the race-based claim. Confident in his eligibility, Saund refused to attack his opponent, eventually winning the primary by more than 9,000 votes.

In the general election, Saund’s Republican opponent was the celebrity flyer Jacqueline Cochran Odlum. Second only to her friend Amelia Earhart, Odlum was the most famous female pilot in the country. She had worked to form the WASPs, Women Airforce Service Pilots, during World War II, owned a successful cosmetics company, lived with her financier husband Floyd at an expansive ranch in Indio and was a close friend of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The race attracted national attention. The New York Times reported: “A woman’s ‘smoldering hope’ and the success story of an East Indian immigrant are converging into what is likely to be one of the most colorful Congressional contests of 1956.”

The Los Angeles Times doubtless thought the copy clever. “Seldom if ever has the American melting pot cooked up a spicier election dish than the contest now simmering in California’s 29th Congressional District.”

The Associated Press reminded readers that Saund was “a Sikh Hindu born in India” with “dark-hued” skin before mentioning that he had been “thoroughly Americanized after 36 years here.”

Odlum wildly outspent Saund on advertising while he quietly campaigned door-to-door. In a last-minute debate one week before the election, Saund was quick-witted and articulate, obviously humble and hard-working. His commitment to local issues won the day. The Washington Post editorial board wrote: “Californians have not always been hospitable to aliens — and especially to aliens of Asian origin. In this election they ignored ancestry and considered the individual.”

Coronet magazine summed it up with a quote from a local farmer: “He’s growed cotton. He’s growed lettuce and beets. He’s worked in hay and he’s worked for wages. And he won’t let any smart aleck lawyers trick him. That’s why we sent him to Washington.”

Concerned with his district, Saund was eager to be appointed to assignments that could help with local issues. He asked to be on the Agriculture and the Armed Services Committees but was seated on the prestigious and powerful Foreign Affairs Committee, where he would serve for his entire tenure in Congress.

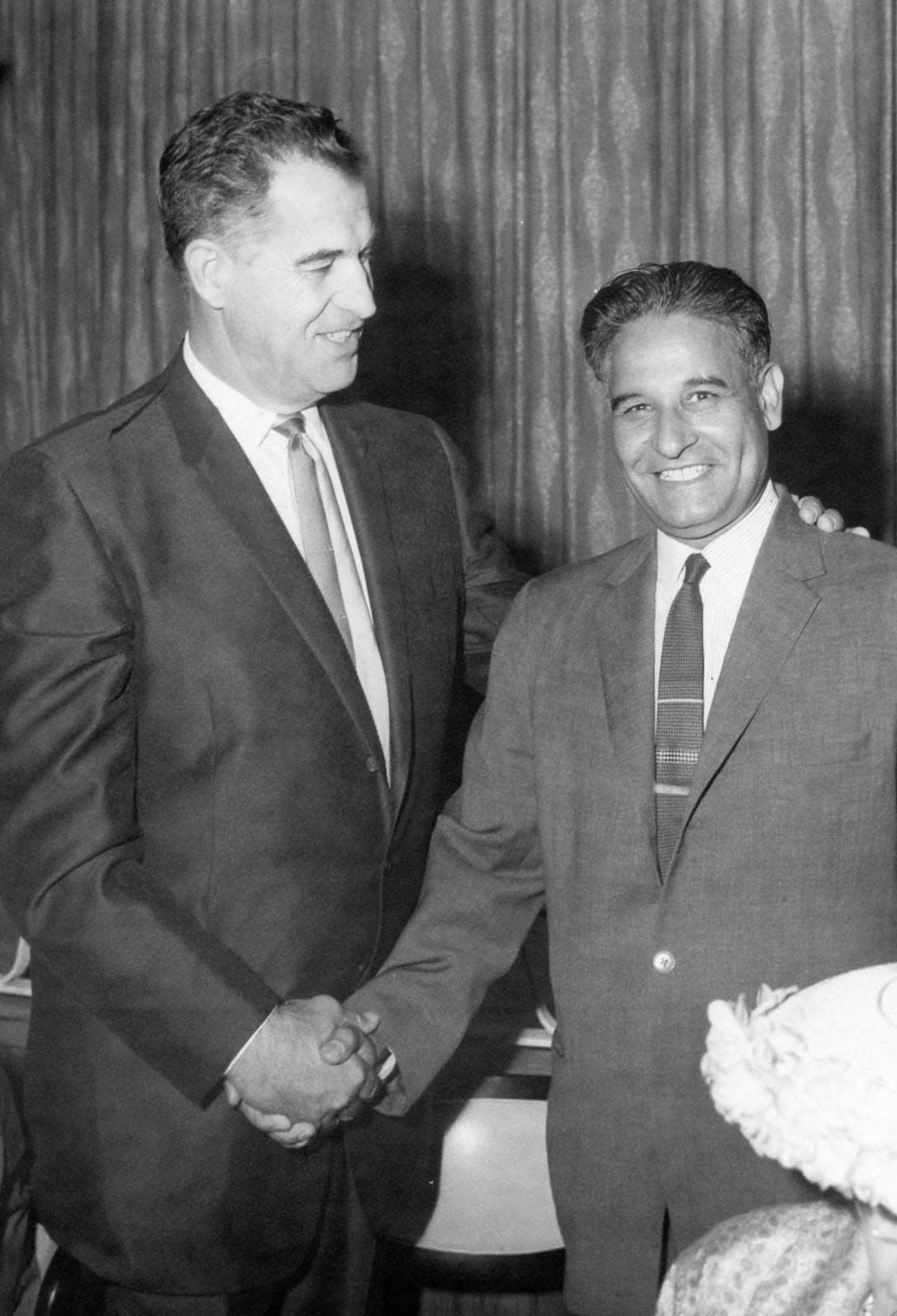

He wanted to see better farm supports. He secured millions for March Air Force Base; collaborated on flood control projects; opened new post offices, built roads, improved airports in the Imperial Valley and assisted scientists in developing new strains of cotton; promoted the Bracero farm labor program; and was a fierce supporter of the 1957 Civil Rights bill. He threw himself into helping the Native Americans in the Coachella Valley, securing permission for long-term leases of reservation lands with tribal chair Vyola Ortner and Palm Springs Mayor Frank Bogert.

Saund was immediately a national congressional star and was featured by the Saturday Evening Post in a six-page article. “His career handicaps seemed insurmountable ... (his) early years as an immigrant dirt farmer, his efforts in civic affairs, his political ambitions and the subsequent ‘high drama’ of the campaign two years ago against Jacqueline Cochran Odlum” yet he was elected to the United States Congress.

Throughout his life, Saund suffered discrimination but thought most of America’s “freedom of opportunity,” saying, “Look, here I am, a living example of American democracy in practice.”

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Palm Springs history: Dalip Saund was democracy in practice