History: Earth, land and the golden checkerboard in Palm Springs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Helen Hunt Jackson in her blockbuster 1884 novel “Ramona” wrote: “There is in this desert one reservation called Agua Caliente, of about 60,000 acres. From the best information we can get, this is all barren desert land with only one spring in it. These desert Indians are wretchedly poor and in need of help perhaps more than any others in Southern California.”

At the end of the 19th century, the dry and forbidding desert home of the Agua Caliente caused the tribe’s extreme poverty, but this location would prove providential one hundred years later by the end of the 20th century.

The administration of Indian affairs by the United States Federal Government is a remarkably complicated and deeply tragic subject that begins at the inception of the country itself and has particular resonance in the desert.

The start of the ruination and relocation of Native Peoples to the so-called “Indian Territory” was affected by sheer force of horrific war and by the Indian Removal Act of 1830 used by President Andrew Jackson to defy the Supreme Court regarding Indian sovereignty and justify the brutal march somewhere between 65 and 110 different tribes to what is now Oklahoma, forcibly removing them from their lands.

In his 1831 ruling on Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia, Chief Justice John Marshall described Indian tribes as “domestic dependent nations” and their relationship to the United States as resembling “that of a ward to his guardian.” This patronizing concept of dependency would persist for decades.

In 1832, just one year later, the Supreme Court reversed itself ruling that Indian tribes were indeed sovereign. But President Andrew Jackson ignored the court over the protests from elder statesmen like Daniel Webster and Henry Clay and set about eradicating the native population.

Fifty years later in 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, known as the Dawes Act, aimed at assimilation as an alternative to extinction of Native Peoples. The head of each Native family would receive 160 acres of tribal land and each single person would receive 80 acres. Title to the land would be held in trust by the United States Government for 25 years. After 25 years, each individual would receive United States citizenship and fee simple title to their land.

Tribal lands not allotted to Native Americans on the reservation were to be sold to the United States, and the land would be opened for homesteading. Proceeds from the land sales were to be placed in trust and used by the government to pay for supplies provided to Native people. The huge tract of Cherokee western land was sold to the United States in 1891 and in 1893, creating a now infamous run on land by eager settlers.

When the allotment process began in 1887, the total land held by American Indian tribes on reservations equaled 138,000,000 acres. By the end of the allotment period Native landholdings had been reduced to 48,000,000 acres.

The concept of owning “land” is a Western European construct that was entirely inconceivable to the Native People to whom land was being allotted. They instead understood the “earth” and its shared sustaining bounty, impossible to possess. The difference between “land” and “earth” in this sense is profound.

The Curtis Act of 1898 amended the Dawes Act, taking the lands of the “five civilized tribes” (Chickasaw, Cherokee, Muskogee, Choctaw and Seminole) and combining it with land identified as “Indian Territory,” creating Oklahoma as a state in 1907. The Dawes Act transferred tens of billions of acres to the U.S. Government for homesteading, oil leases, national parks and more. It was the largest land grab in U.S. history.

The remaining land was to be “allotted,” or given to individuals for their own use contrary to their deeply spiritual understanding of the earth. The Federal government and the Bureau of Indian Affairs now call allotment a “repudiated policy.” But the issues wrought by this practice and administration of it were extremely difficult and in the Coachella Valley, quite distinctive.

The Palm Springs reservation was created in 1876 by President Ulysses S. Grant and it was later expanded by Presidents Hayes, Cleveland, Roosevelt, Taft and Harding.

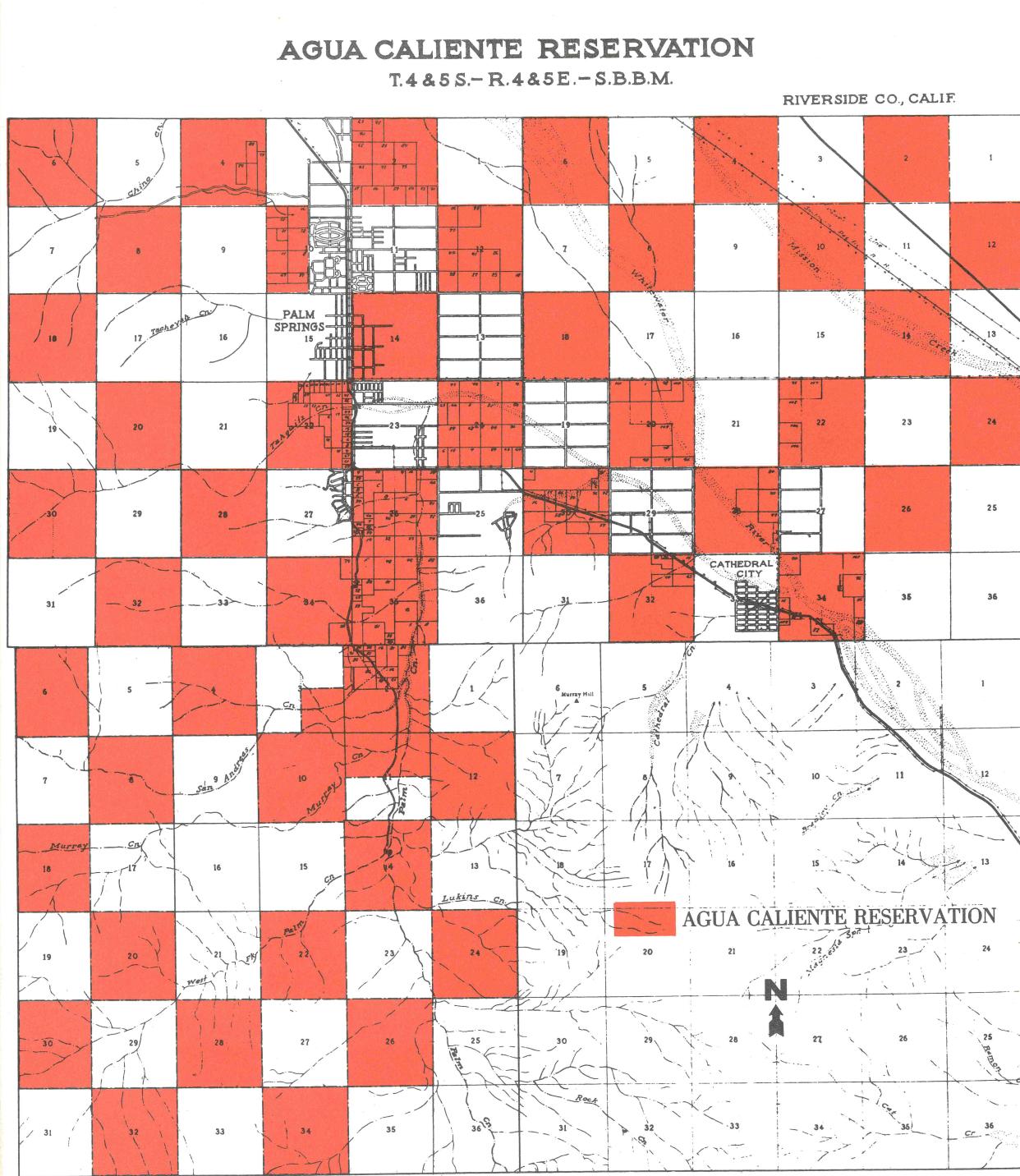

The reservation is a unique checkerboard pattern of alternating square miles, leftover after the federal land grant to the Southern Pacific Railroad intended to induce the building of the transcontinental railroad lines. In 1917 Congress authorized these reservation lands to be allotted to individual members of the Agua Caliente Tribe, with title to be held in trust by the Federal Government.

However for decades, the Secretary of the Interior failed to execute the allotment, resulting in lawsuits known as the St. Marie Cases filed in 1936. At the time there were 50 members of the Agua Caliente Band. In his 1966 report, Palm Springs City Manager Frank Aleshire wrote: “For the next 25 years the whole question of the right of the individual Indians to title to reservation lands was hopeless ensnarled in a series of lengthy and confusing lawsuits.”

When the City of Palm Springs was incorporated in 1938, within its boundaries were some 8,000 acres of Indian land.

In 1949 the Congressional Committee on Indian Affairs wrote: “Administration of the restricted lands on the Agua Caliente Indian reservation has presented a unique problem to the Federal government. It is the only place in the United States where restricted Indian land is intermingled in a checkerboard pattern with highly developed urban land of great value.”

Leases of Indian land had been limited to five years, making development impossible. Yet, this tribal land was interspersed in the alternating checkboard pattern with fee land and was highly desirable because of its location.

Extensive lobbying by the intrepid and sophisticated all-female Agua Caliente Tribal Council led by Vyola Ortner, with the assistance of Riverside Congressman Dalip Singh Saund and Palm Springs Mayor Frank Bogert, resulted in President Eisenhower signing into law in 1959 an act to “equalize” the value of allotments to individual tribal members and an amendment to the Indian Leasing Act to authorize the Secretary of the Interior to allow allotted as well as tribal lands to be leased for 99 years, making such lands economically viable and extremely valuable.

The checkerboard was now truly “golden,” and the once destitute Agua Caliente people Jackson had observed as most wretchedly poor were on their way to finally administering their own land for their own prosperity.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Palm Springs history: Earth, land and the golden checkerboard