History of equalization of property rights by members of Agua Caliente Band of the Cahuilla Indians

The struggle for the property rights of the individual members of the Agua Caliente Band of the Cahuilla Indians has been long and difficult. In 1958, Tribal Council Chairman Vyola Olinger (later Ortner) presided over “one of the biggest real estate deals in the country” in championing the rights of her people.

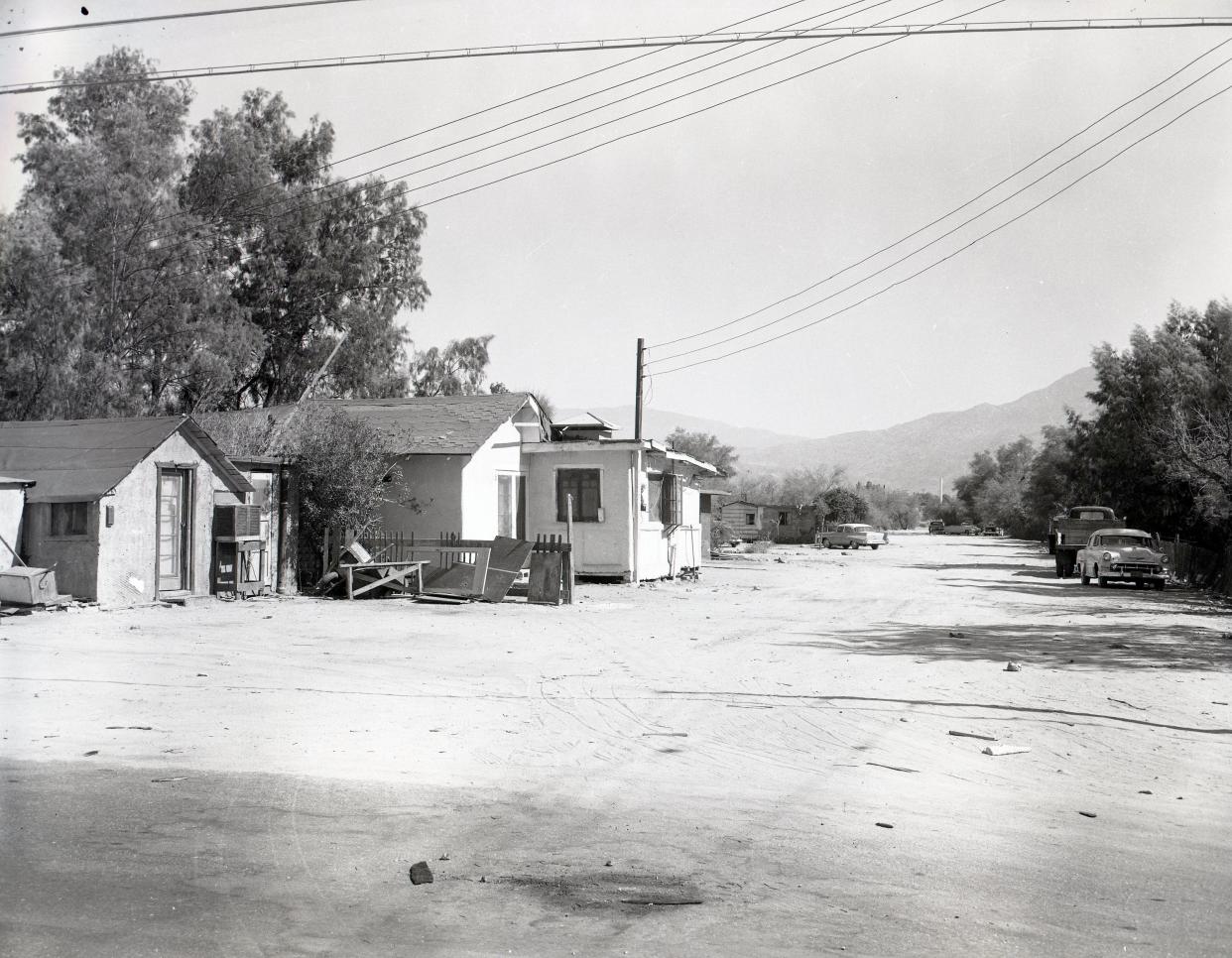

The heart of the reservation of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians is Section 14, a 640-acre parcel in the center of downtown Palm Springs. It was at the center of a possible multimillion-dollar development opportunity that was crucial for the Tribe’s survival.

Two issues needed to be adjudicated before any development was possible. The first was to finalize the equalization of values of individual allotments, parcels of land given to each tribal member, and the second was to increase the time that tribal members could lease their land in order to attract developers.

Allotment of the land on the Palm Springs reservation, originally established under 1891 law, to individual members of the Agua Caliente Band was begun in 1923. Because of various complications in legislation, administration and litigation, the first allotment schedule was not approved by the Secretary of the Interior until 1949.

A decade-long battle began when an attempt to “equalize” allotments of land to individual members of the tribe was made by the federal government. Making the values of allotments equal and fair to all tribal members was a daunting task. Allotments varied considerably according to Native American expert Dr. Lowell Bean in his book From Time Immemorial.

In 1954, Clemente Segundo et al vs. United States was settled with a ruling that each plaintiff in the case was to be allotted “total lands of as nearly equal value to the lands allotted to each of the other members.” This decision by the court ended the legal back-and-forth of individual tribal members and the federal government, setting up the framework for both individual members’ property rights and the Tribe’s future.

The question of how to equalize the values of real estate was studied by the federal government through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the all-female Tribal Council led by Vyola Ortner. According to an article published in the Desert Sun on Feb. 13, 1957, four solutions were proposed: 1) Dividing the tribal lands 2) Selling the tribal lands and distributing the money 3) Using tribal land income as a dividend to allottees 4) Combining two or more of the above-mentioned plans.

On June 14, 1957, comments were made through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, by the United States Department of the Interior, Office of the Secretary, stating that to make the management of tribal and individual assets more manageable a corporation should be managed by appointed people familiar with corporate ways. The allotted lands would be turned over to the corporation and tribal members would receive stock in the corporation. The reservation would be sold off and the proceeds distributed to tribal members.

At a hearing held on Oct. 2, 1957, Tribal Chairman Vyola Olinger (Ortner) said in her testimony, “that the Indians felt that the bill established a liquidating corporation, one that would sell as rapidly as possible their tribal lands…and was not acceptable to the members of the Tribe.” She proposed that except for tribal reserves all other lands would be allotted and Congress should pass a bill to complete the equalization.

Rex Lee of the BIA announced on June 25, 1958 that tribal lands (31,610 acres valued at approximately $12,000,00 by the Secretary of the Interior in 1957) would be divided up with the goal of bringing each member’s land value up to $350,000 and any member whose allotments were already valued between $87,000 and $629,000 would not benefit from the changes.

On July 19, 1958, the BIA received a letter from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs telling him to proceed with the process of allotting the land including the reserves (land held by the tribe collectively.) The Tribal Council responded by declaring that they would wage an all-out war with the federal government’s equalization program saying that it would “liquidate” and destroy the tribe itself.

Ortner said that the government’s plan, “creates an economic and culture crisis for both the City of Palm Springs and the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians.

Later in the summer, Associated Press reporter John Beckler reported that “BIA Director, Leonard Hill, admitted that plans for developing Section 14 as a single package had fallen through.” Beckler added, “Real Estate people now are faced with the problem of dealing with the Indians on an individual basis and developing in a piecemeal fashion.”

In an article in the Desert Sun published on July 29, 1958, Ortner asked the City of Palm Springs for help. She stated that even though tribal members were allotted over half of the real estate within the city limits, they were “land rich but cash poor.”

In a combined lobbying effort between Congressman D.S. Saund, The Agua Caliente Tribal Council, and the City of Palm Springs, Public Law 86-3327 and Public Law 105-308 were passed by the House of Representatives, and the Senate and signed into law by President Dwight Eisenhower on Sept. 21, 1959.

The Equalization Bill (Public Law 105-308) authorized the allotments to be equalized with the target of the value set at $350,000 and the Land Lease Act (Public Law 86-327) authorized increasing the leasing period to a maximum of 99 years. Anyone not alive before Sept. 21, 1959, was excluded from the equalization process and would not be allotted land.

In accordance with this law, most of the reservation land was allotted to 92 individual members (31 adults and 61 minors) except for the lands held by the tribe in common which included two cemeteries, the Catholic Church located on Section 14, Our Lady of Guadalupe, the hot mineral spring including the area around it, and the lands in Tahquitz, Palm, Murray, and Andreas canyons.

The tribal members were able to stop the incorporation and complete land liquidation proposal, but the associated notion of appointment of guardians and conservators for all minors and adults judged as “incapable to handle their own affairs” was passed by Congress and created another struggle for the native people of Palm Springs.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: History of equalization of land by members of Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians