History meets storytelling

A funny thing happened on my way to writing a Senior Living piece for March. I meant to write about having “the talk” between aging parents and adult offspring, but I got waylaid by an ORICL class (Oak Ridge Institute for Continued Learning).

In February, Emily Jernigan and I led a two-session class for ORICL on "Storytelling and the Flatwater Tales Storytelling Festival."

For full disclosure, Emily and Charles Jernigan, Pat Postma, my spouse David Hobson and I founded the Flatwater Tales Storytelling Festival in June 2018. We began planning in 2017, after a conversation held in the middle of a blocked-off street in Jonesborough during the National Storytelling Festival.

Emily chairs the Flatwater Festival, and now Charles Crowe and Lydia Birk have joined the founders on the executive committee for the venture, which is a project of the three Oak Ridge Rotary clubs. The Festival has a larger committee of some of the most creative people in the community.

In doing some background checking for our class, I encountered the story of a man who took a tiny town that was not just sleepy, but “decaying,” and propelled it into the international spotlight. And this community now has tremendous economic impact for its region. The town is Jonesborough.

The oldest town in Tennessee, Jonesborough was a happening place even as a dirt village when it became the provisional capital of the State of Franklin in 1784. It is said that it was a watering hole for Andrew Jackson as he rode across from North Carolina to Nashville. Some of its original inns are still in business.

Now, the State of Franklin was in upper East Tennessee near the Western North Carolina border, not Franklin, the suburb of Nashville, where rich Tennesseans and the governor live.

Even though all eight counties that formed the State of Franklin are now part of Tennessee, they belonged to North Carolina in 1784 and extended as far west as our neighboring Blount County.

The new country was operating under the Congress of Confederation at the time. Although it had never been assured that the land West of the original 13 colonies would become part of the new fledgling country, the State of Franklin wanted to become the 14th colony, or state, four years before the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and five years before the inauguration of President Washington.

Chaos had ensured in the colonies and on the frontier, especially on the frontier, following the Revolution. Also, the colonies were pretty deeply in debt after the Revolution, and, at first, North Carolina wanted to give the land of the eight counties to the centralized government to pay part of its debt. It had even been rumored that the centralized government would take the land and sell it to Spain to help defray part of its debt.

The frontier people, however, took things into their own hands and tried to form a new state. The State of Franklin negotiated its own treaties with the Muscogee and Cherokee people. In truth, of course, the land had been stolen from the indigenous people.

John Sevier was governor of the State of Franklin and was Tennessee’s first governor when Tennessee became the 16th state to join the union in 1796.

The State of Franklin never got traction to join the other colonies. Benjamin Franklin, gracious in his refusal letter to help the State of Franklin, explained that he had been in Europe at the time the State was formed and did not know enough about it to help it. He thanked the founders for the honor of the name, and he did say that, if he ran across anything that could be helpful, he would let them know.

In 1789, the year President Washington was inaugurated, the State of Franklin just sort of imploded, and the land reverted to North Carolina.

The Smithsonian Magazine makes an interesting observation, however: “Although the State of Franklin rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, it did contribute to the inclusion of a clause in the U.S. Constitution regarding the formation of new states. The clause stipulates that while new states ‘may be admitted by the Congress into this Union,’ new states can’t be formed ‘within the jurisdiction of any other State’ or States unless the state legislatures and Congress both okay the move.”

After the demise of the State of Franklin, for more than a century and a half, Jonesborough languished. It wasn’t just a sleepy village; apparently it really was decaying.

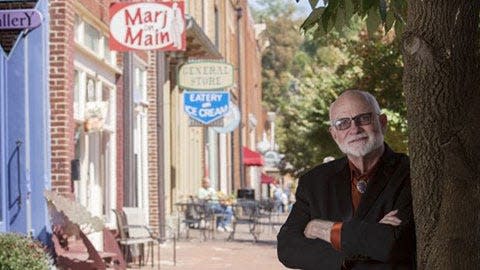

Then along came Jimmy Neil Smith, the man who fixed it.

A native of Jonesborough, Smith was a journalism teacher in the local high school. One day, he had a group of students in the car going to a nearby town to have the student newspaper printed, and they were listening to Jerry Clower on the radio. Clower was the Mississippi humorist popular in the South in the 1970s. Smith turned to his students and said, “Wouldn’t it be nice if Jonesborough had a storytelling festival?”

Smith says that at the time he did not know what a storytelling festival was, but he knew what a festival was and he knew what storytelling was.

As Smith planned that first festival, he asked a friend whether calling it “The National Storytelling Festival” was presumptuous. She asked whether there were other storytelling festivals in the country. “Not as far as I know,” Smith replied. And his friend said, “Let’s be presumptuous.”

Smith and fellow residents held that first National Storytelling Festival on an old wagon in Courthouse Square for an audience of 60 listeners in 1973. Smith said he knew people would come back the next year and the next for the festival.

Two years after that first Festival, Smith founded the National Association for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Storytelling — now known as the International Storytelling Center.

Smith served as mayor of Jonesborough from 1978 to 1984. He was also president of the International Storytelling Center until 2012. He took a sleepy village from obscurity to international recognition — through storytelling.

That recognition comes with untold social advantages and a multi-million-dollar impact for the region. Next month, we’ll describe how those social and economic advantage have continued since 2012.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day to all those who are Irish and to the rest of us who wish we were.

Martha Moore Hobson was an early CFP™ in the region. Although retired, she is still a volunteer in the community.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: History meets storytelling